Opinion: What the new net neutrality rules really mean for ISPs

Critics of the Federal Communications Commission’s new net neutrality rules contend that they put the government in control of online content while burying Internet service providers under an avalanche of regulations that kill investment, raise prices and slow connection speeds.

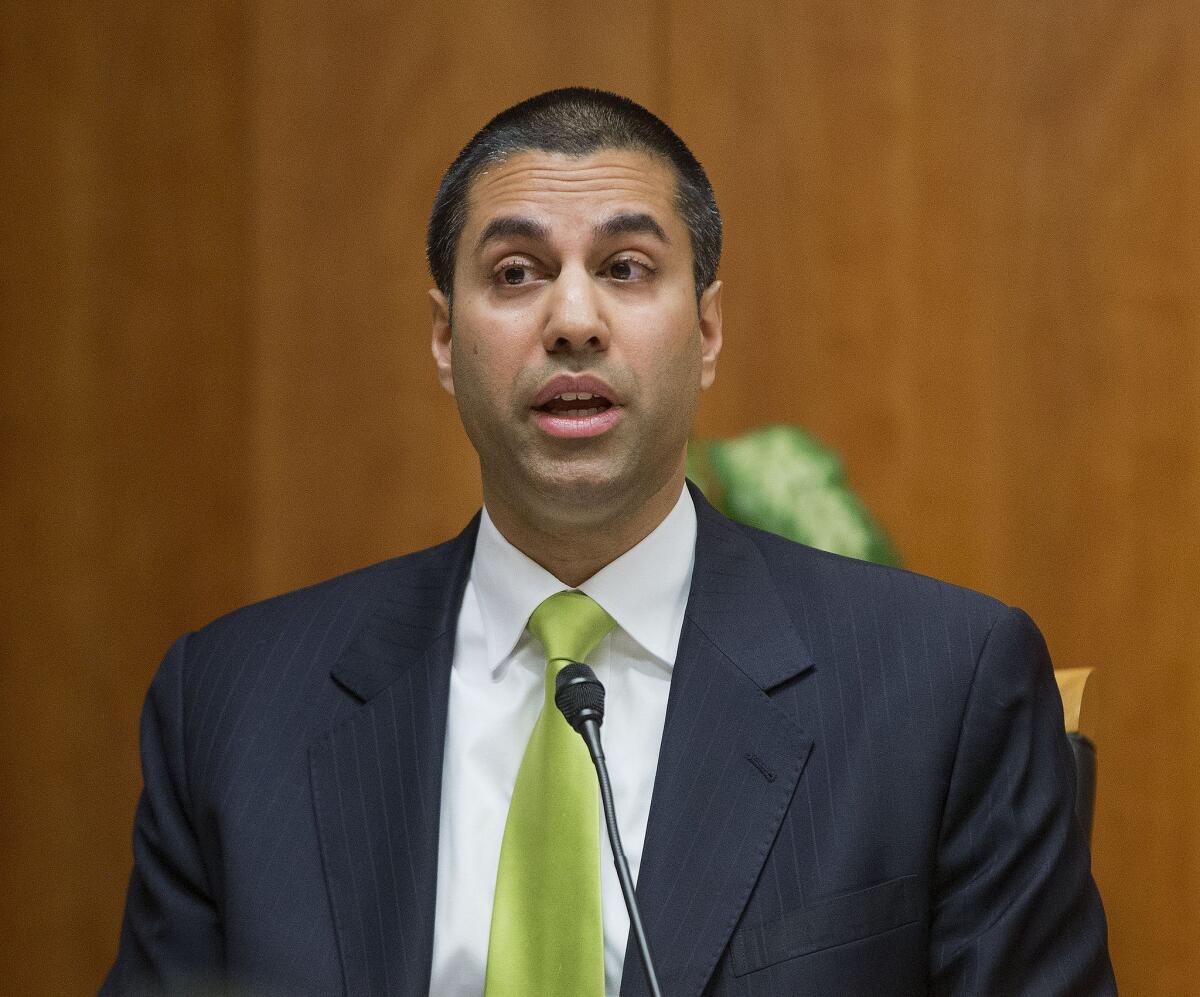

“To paraphrase Ronald Reagan,” said Commissioner Ajit Pai, who voted against the rules, “President Obama’s plan to regulate the Internet isn’t the solution to a problem. His plan is the problem.”

Pai, one of two Republicans on the five-member commission, could just as accurately have called it “John Oliver’s plan,” given that Oliver helped pump up the demand from Internet users that the FCC take a tougher approach than Chairman Tom Wheeler initially proposed. But never mind his partisan framing, which is of a piece with Sen. Ted Cruz’s “Obamacare for the Internet” formulation. Implicit in Pai’s criticism is the notion that the FCC is trying to govern the Internet as a whole, and that’s a more damaging bit of hyperbole.

Based on what the agency has said so far, it’s clear that the new rules apply only to the on-ramp people use to connect to the Net, not the content flowing over it. They don’t regulate the Internet, they regulate the companies that connect you to it.

The comparison to local phone companies is instructive. Over the course of the 20th century, the FCC and state utilities commissions used Title II of the Communications Act to apply a mountain of rules to the Ma Bell family and other local phone monopolies that regulated their prices, service areas and quality. But those rules never affected what people could say on the phone. To the extent that the content of those conversations was regulated -- for example, the “do not call” rules for telemarketers and the strictures on phone sex services -- those regulations stemmed from other laws, not Title II.

Similarly, the FCC is applying Title II only to “broadband Internet access services,” not the sites, applications or services that people connect to through their broadband ISP. The agency is regulating the people who operate the communications equivalent of an essential toll road, not the vehicles or people traveling over it.

The caveat is that the commission hasn’t released the text of its rules yet, a delay that Wheeler attributed to the need to incorporate and respond to the (stinging) dissents filed by Pai and his fellow Republican commissioner, Michael O’Rielly. Some critics contend that the new rules extend the FCC’s regulatory reach to the sites and services that interconnect directly with broadband ISPs, such as Netflix and Akamai. The commission’s summary, however, says that the interconnection rules apply to the ISPs’ activities, not those of other players.

But what about the aforementioned mountain of Title II rules? Won’t they crush ISPs?

In a word, no. The reclassification is prospective, not retrospective. Again, this is based on what the FCC has said about the rules, not the actual text that may still be evolving. But according to the agency, the commission formally waived (“forbearance” in FCC-speak) more than 700 existing Title II regulations so they wouldn’t apply to ISPs, leaving in place a handful of procedural rules that apply to the filing of complaints.

The commission also has declared that numerous sections of Title II do not apply to ISPs, such as the ones that gave the commission the power to review a phone company’s rates in advance. What it left in place were the fundamental requirements that a service’s charges and practices be “just and reasonable” and that it not engage in any “unjust or unreasonable discrimination,” along with rules governing the disclosure of personal information, access for the disabled and the ability to use utility poles.

Granted, the FCC could come up with additional rules based on the sections of Title II it did apply to ISPs. And future commissions could try to re-apply sections that this commission waived. But considering how hard-fought the neutrality rules have been (and continue to be), any attempt to impose more regulations would be an exceptionally tough slog.

Harold Feld, a communications law expert at Public Knowledge who supports the new rules, said the FCC’s Republican critics argue that regulatory agencies are inherently untrustworthy, so Title II will inevitably be applied in a heavy-handed way. “They have been doing their best to crate an impression that there is something out there that is lurking that, no matter what anyone says or does, is just poison that is waiting to leap” onto ISPs, Feld said. “That’s just silly.”

Realistically, reclassification will have two main effects going forward. First, it provides a more solid legal foundation for the new net neutrality rules, including the prohibitions on ISPs blocking lawful content, throttling data streams and prioritizing traffic for a fee. And second, it allows consumers and online “edge providers” -- websites, online services and apps -- to bring complaints against ISPs based on the remaining sections of Title II and a new “general conduct standard” created by the commission.

The latter, according to the commission, says ISPs may not “unreasonably interfere with or unreasonably disadvantage” edge providers or consumers as they try to provide or use lawful content, applications, services or devices.

Although the general conduct standard relates to net neutrality, the reclassification exposes ISPs to complaints on other issues as well. In particular, it will make it easier for consumers to challenge their ISPs’ prices, data caps, privacy policies and other terms of service. Under the new rule, those complaints can be taken either to the FCC or to federal court.

Of course, ISPs can (and often do) eliminate the threat of such complaints by requiring subscribers to take their beefs to arbitration, not to court. And even if a complaint about an ISP’s prices makes it into court, Feld said, Supreme Court precedents require that the prices be presumed to be reasonable because the FCC no longer requires them to be approved in advance. “What constitutes reasonable is extraordinarily broad,” he added.

In sum, the FCC isn’t “regulating the Internet,” and it’s not taking a telephone book’s worth of dictates from the 20th century and applying them to ISPs. It is exposing ISPs to more complaints, though. How it handles those will determine just how big a change the new regime will be from the old one.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.