The West’s defender of wild places

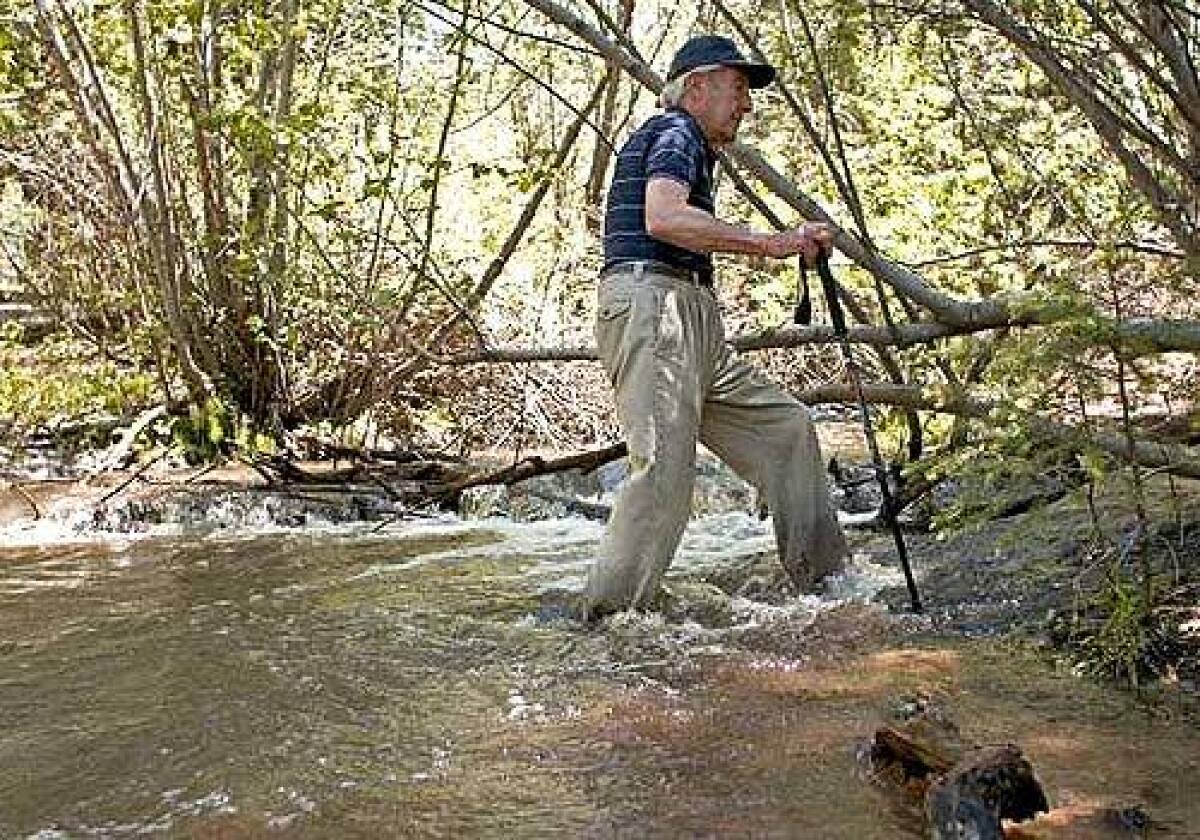

On a late spring day, with streambeds roaring and the sun breaking through the thin mountain air, Stewart Udall has just crossed a calf-deep creek, rushing with late-season snowmelt from the western slope of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in northern New Mexico. His corduroy pants are drenched at the cuffs, his sneakers muddied and soaked. Udall is on the Rio en Medio Trail, a popular and well-watered seven-mile hike a good half hour out of Santa Fe.

FOR THE RECORD:

Wilderness protection —An article in Tuesday’s Outdoors section about former secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall said the Wilderness Act protects more than 400 million acres. The act protects more than 100 million acres.

Udall, who turned 85 in January, has slowed down in recent years. Age, the death of his wife and a degenerative eye condition have contributed, but once on the trail, he gamely sloshes ahead, grasping drooping branches and, if needed, an outstretched hand.

“This is good wilderness,” he says, his somber voice lightening up. “Any time you have to struggle a bit to cross a stream you’ve got good wilderness.”

Good wilderness. That’s what Udall can boast about. As secretary of the Interior during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations — and one of the architects of the Wilderness Act — he is perhaps the politician most responsible for the public lands you hike, the rivers you kayak, the mountains you climb and the wilderness you contemplate. And it is this legacy that he is most fearful will be lost.

Along with Robert McNamara, Udall is the last surviving member of the original New Frontier cabinet. In his ninth decade, he continues to put forth an environmental agenda, laments the dismantling of national lands and bemoans the malicious attitudes that he sees corrupting Washington. The family name is synonymous with public service: Both a son and a nephew are in the U.S. Congress, and his brother Morris, who died in 1998, was a longtime Arizona representative and onetime presidential candidate. Still, Stewart Udall realizes he is of a distant generation.

“I’m living out my life as the last leaf on the tree,” he says.

The Wilderness Act was a radical piece of legislation in its day, calling for “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Today the Wilderness Act protects nearly 5% of the country’s land, encompassing more than 400 million acres in 44 states.

The legislation was so complicated that it took 10 years of shaping and crafting before it could be successfully introduced to Congress. The Wilderness Preservation System, as the bill was formally known, became law in 1964, gliding through the House, 374-1, and the Senate, 72-12 (due in large part to California Republican Thomas Kuchel). The law, along with other Great Society initiatives, helped redefine American life, and it came about in large measure as a result of Udall’s public and private persuasion.

A young family of three, the baby strapped to its father’s chest, walks past Udall with a nod, while its dog races ahead.

“When you see families like that, you’re seeing real outdoorsmen,” he comments after they pass. “Modern life is a conspiracy. Everything is against health. Television tells you to sit, sit; eat, eat. People need to get out of doors. Exercise.”

Udall can be a scold, however righteous he may feel. The word “curmudgeonly” comes to mind. Some have called him “the troubled optimist.”

A diplomat who worked both sides of the aisle, Udall finessed the Wilderness Act by invoking not the social programs of FDR but the national park initiatives of Teddy Roosevelt. He shrewdly drew attention to the growth of the Sierra Club and the popular awareness of the environment that had been sparked by Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” and, to a lesser extent, his own Wallace Stegner-inspired “The Quiet Crisis,” about the history of America’s environmental movement. The legislation, coupled with other laws, has made the Udall years at Interior the historical high-water mark for preservation and conservation. The Wilderness Act, said one ardent supporter, turned poetry into policy.

Farther into the national forest, Udall zigzags across the stream half a dozen or so times. His cane is a carbon hiking stick, and he leads with a brisk pace. The forest, he points out, is reminiscent of St. John, Ariz., on the Colorado Plateau where he grew up.

“I was never much of a botanist,” says Udall. Hefty pine cones lay around the tree trunks; a swarm of small purple butterflies flutters by. “I can tell a ponderosa when I see one. It’s one of my favorite trees. Coronado walked through ponderosas when he traveled here. My favorite tree in New Mexico is the aspen, but we’re not high enough. In St. John we had some cedar and some juniper at 5,500 feet.”

Conversant with politicians, radicals and actors, Udall has been at the center of some of the great Western environmental conflicts of the 20th century: the Central Arizona Project, for instance, and the Glen Canyon Dam (he supported the former and regrets the latter). Memories for him are less moments of nostalgia than reminders of what can be done.

“Pete Seeger sang at a fundraiser we put on for the Navajo uranium miners once,” he remembers. “Ed Abbey was there, too. I respected Abbey, and I suspect he respected me. The Atomic Energy Commission didn’t tell uranium miners about the lung cancer possibility. They knew all along there was going to be an epidemic. If they’d told the miners about the possibility of cancer they’d have quit, and it would’ve affected the production of bombs.”

Udall spent some 10 years representing lung-damaged miners, losing in the U.S. Supreme Court but winning compensation for them in Congress.

With his angular face and swept-back silver hair, Udall has a Mt. Rushmore profile. His friend Robert Redford says his face has the bearing that deserves to be on the back of a nickel. Their friendship goes back to 1970, when the actor invited the politician to chair the nonprofit Sundance-based Institute for Resource Management.

“It was pretty clear that this guy was devoted to not only the land, but the history of the West,” Redford says. “He represents a great part of our country and a great time in our country that has sadly evaporated. He and I became very, very close in the ‘80s.”

Today Redford is coaching Udall on a screenplay he’s writing, set on the Colorado Plateau and drawing on the Mountain Meadows Massacre, the notorious incident in southern Utah in which a Mormon militia and Paiute Indians attacked a wagon train headed for California, killing more than 100 settlers.

“He’s pretty rich in lore,” says Redford, “but translating that to the screen is a gigantic task. This last year has just brought us together even more as he reaches his emeritus stage. My affection for him is so keen.”

On the trail, Udall passes hikers, most on their way to the waterfalls and beyond, up the back side of the Santa Fe Ski Area. The sun has dried his stream-soaked cuffs. Next to a huge rock he pauses and rests his head against the lichen.

In his Cabinet days, he hiked both Japan’s Mt. Fuji, at 12,387 feet, and Mt. Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, at 19,340 feet. “Kennedy wanted us to show some ‘vigah.’ ” (A framed photo of Udall on Kilimanjaro hangs on his home office wall.)

On weekends during his Cabinet days, he and the family would pile into the car and drive to Interior Department outposts in the Washington area, among them the Washington Monument, where they’d climb the stairs to the top for exercise. When school was out, the family would raft on Western rivers: the Colorado, the Salmon, the Green, the San Juan.

Just this last year he rafted down the Colorado River from Lees Ferry — named for Udall’s grandfather — and, with a grandson, trekked from the floor of the Grand Canyon up Bright Angel Trail some 7,000 feet to the South Rim. His family had cautioned against it, and he rejected a Park Service offer of a mule. “They wouldn’t have liked it if I hadn’t made it,” he recounted, “but what a way to go.” Once at the South Rim, Udall marched straight to the bar at the Tovar Lodge and ordered a martini.

Udall stands on the bank of the stream, having just crossed it again, when a couple splashes up behind him and does a double-take.

“You you’re you’re Stewart Udall?!”

The two suddenly gush with unrestrained admiration. Udall nods slightly, his stoic face breaking into a tight smile of appreciation. As the couple trots off, he looks at a tree in the middle distance. He’s quick to deflect attention and eager to focus on what really matters.

“That’s a willow, I think.”

*

Tom Miller is the author of “Jack Ruby’s Kitchen Sink: Offbeat Travels Through America’s Southwest,” winner in 2001 of the Lowell Thomas Award for Best Travel Book of the Year. He lives in Arizona.

*(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

EXCERPT

Turning poetry into policy

As secretary of the Interior, Stewart Udall used the pulpit to lobby for the Wilderness Act. In an article he wrote for a labor magazine, he considers the spiritual importance of wilderness.

[Wilderness] areas offer more than delights to the senses — they offer the challenge of wilderness experience to those hardy enough to accept the challenge of the outdoors. The plea for intact wilderness means more than mere preservation of some last remnants of the grandeur that once was America. It means a chance for young and old to pit their human resources against the earth and the elements. This opportunity will vanish if wilderness is allowed to vanish. Wilderness will not suit all tastes. It offers something worthy of your mettle — both physical and spiritual. I am convinced that it is our national character, as well as some pieces of our wild land, that stands to be preserved by passage of the Wilderness Bill . We need to preserve places where nature can maintain her own balance, set her own pace. These natural places, completely untouched by the hands, the machines, the tools of man, are absolutely essential as laboratories of life — yardsticks against which to measure our efforts to improve the environment, as well as our dismal successes in destroying it.

—From “We Must Save the Beauty of Our Land,” April 1964, Carpenter magazine