Single dose of Ebola vaccine works rapidly in monkeys

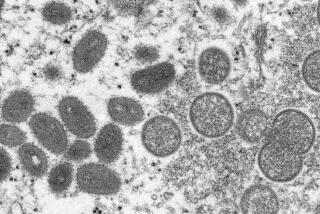

A single dose of an experimental vaccine protects macaques within seven days from infection with the strain of Ebola virus currently sickening people in western Africa, researchers have found, and it begins to confer some protection against the virus within as few as three days.

The discovery, reported Thursday in the journal Science, fills gaps in scientists’ knowledge about how new vaccines stave off Ebola disease -- and could signal good news for the battle against the infection in West Africa.

“I was very, very pleased,” said study coauthor Andrea Marzi, a virologist at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Hamilton, Mont. “I think it’s very encouraging to have a vaccine that works with a single dose so quickly.”

The vaccine, known as VSV-EBOV or rVSV-ZEBOV, is the same that was reported last week in the journal Lancet to have been highly effective in a separate trial in human subjects in Guinea. In that trial, people in close contact with newly diagnosed Ebola patients were offered vaccination. People who received doses without delay were protected from infection, researchers found.

For this trial, Marzi said, researchers hoped to pinpoint exactly how long it takes for the VSV-EBOV vaccine to stimulate immunity in cynomolgus macaques, a laboratory animal used often in research. Fifteen monkeys were randomly divided into groups of two or three animals. The groups were immunized with the Ebola vaccine at 28, 21, 14, seven or three days before being injected with a lethal dose of Ebola virus (a control group of three had been immunized with a Marburg virus vaccine).

The control animals and one of the monkeys in the Day Three group developed severe Ebola disease and were euthanized. Another monkey in the Day Three group got moderately sick but recovered; the third had only slight signs of illness and also survived.

All of the other monkeys had no signs of disease, indicating the vaccine had prevented infection.

The researchers’ primary aim was not to describe how VSV-EBOV works -- they had addressed that in earlier work -- but they did perform some further tests to try to understand how the monkeys in the Day Three group that survived had been protected. They noticed that the vaccine seemed to trigger an innate immune system rapid response, activating cells called macrophages and natural killer cells to attack invaders. That might help buy time for the monkeys’ adaptive immune systems to develop T-cells and antibodies to target the Ebola virus, Marzi said.

Understanding how the vaccine works could help make a difference in affected countries. Last year, Marzi and her NIAID colleagues were deployed to Liberia to work in an Ebola diagnostic lab for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It was an eye-opening experience, she said.

“When we got there, we realized how many people are deployed, and we thought it was worth asking the question quickly: ‘If there was a vaccine to give to those people, how long before their deployment would they need it to be safe?’” she said. “It was always an interesting scientific question. But participating in the effort brought it to the front of our minds.”

She said the research team would next like to study whether the VSV-EBOV vaccine could work as a treatment for Ebola after exposure to the virus.

For more on science and health, follow me on Twitter: @LATerynbrown