Florida man awakens in Palm Springs ER speaking only Swedish. Why?

It’s a story that is captivating people on both sides of the Atlantic.

On Feb. 28, the Desert Sun newspaper reported, a man was discovered unconscious in a Motel 6 in Palm Springs. He was taken to the hospital, where he awoke in the emergency room.

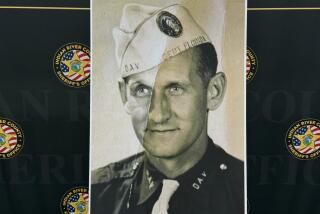

Four pieces of identification the man carried indicated that his name was Michael Thomas Boatwright. But the man couldn’t remember his name and didn’t recognize his own face on his California ID. He believed his name was Johan Ek. He spoke only Swedish.

Today, more than four months later, Boatwright’s caretakers know a bit more about their patient — he was probably born in Florida, is a veteran and spent some years in Sweden during the 1980s — but Boatwright reportedly still doesn’t remember much about his past and still isn’t speaking English. He remains hospitalized while medical staff figure out how to release him safely into the world.

While stressing that they had not examined Boatwright directly, neurologists and psychologists contacted by the Los Angeles Times said that the man’s condition most likely stemmed from a psychological — rather than a physiological — cause.

Dr. Robert Bright, a psychiatrist at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., said that he looks for one of three different things when he encounters a patient with memory and identity loss.

First, he said, is the possibility that “some sort of medical, organic thing has caused an insult to the brain,” such as a traumatic brain injury, a stroke, a seizure, loss of oxygen or an infection. In such cases, however, patients usually have memory loss around the time of the incident but are unlikely to lose their sense of identity or their ability to speak in their native tongue, or to forget more remote events in their lives, Bright said. Doctors would usually also see something abnormal on an MRI, he added.

Thus far, there have been no reports of red flag test results in Boatwright’s case.

“It would be highly unlikely for this to be because of a problem with the brain,” agreed UCLA behavioral neurologist Dr. Mario Mendez. “Events from the distant past are relatively retained. Especially if they’re strong, personally referent items — things you’ve heard all your life. From a neurologic point of view, it would be very unusual to lose such fundamental information.”

The second — and highly more likely — possibility, the Mayo Clinic’s Bright said, was that there was a psychological cause and the patient is experiencing what’s known as dissociative fugue, or global psychogenic amnesia. With such patients, whose unconscious break from reality may be a form of self-protection, “there tends to be a wall — they don’t remember anything,” he said.

“A lot of these people will have a history of a psychiatric condition — depression, for example, or PTSD — and there’s typically an acute stressor that triggers the event,” he added.

We don’t know what might have happened to Boatwright. But his brain may have essentially shut down and “gone back to this other time and place” — Sweden — for a reason, Bright said.

“Maybe Sweden was a place of less stress” for Boatwright, he said.

The third possibility, Bright added, is that Boatwright is malingering — consciously making the whole thing up — to avoid some kind of trouble.

Bright said that determining when patients are faking memory loss is difficult for psychologists, who usually can make that call only when they figure out what the patient gains by lying. “You find out [the patient] is wanted, or he’s about to go to prison,” Bright said.

If Boatwright’s identity loss does stem from psychological causes, Bright added, his doctors and nurses should be able to help him pull out of it by treating the underlying issue — offering psychotherapy or medication to address depression, if that’s indicated, or working with family to alleviate relationship stress if that was the trigger.