On Kentucky’s Bourbon Trail

Yo, Napa Valley winemakers, better watch your backs. The South is rising again, this time in a battle for tourist dollars.

In an effort to win hearts, minds and a larger market share, the bourbon distilleries of Kentucky are “taking a page from the book of California’s vintners,” said David Pickerell, head of production for silky-smooth Maker’s Mark bourbon whiskey.

They call it the Bourbon Trail, and it’s an unabashed imitation.

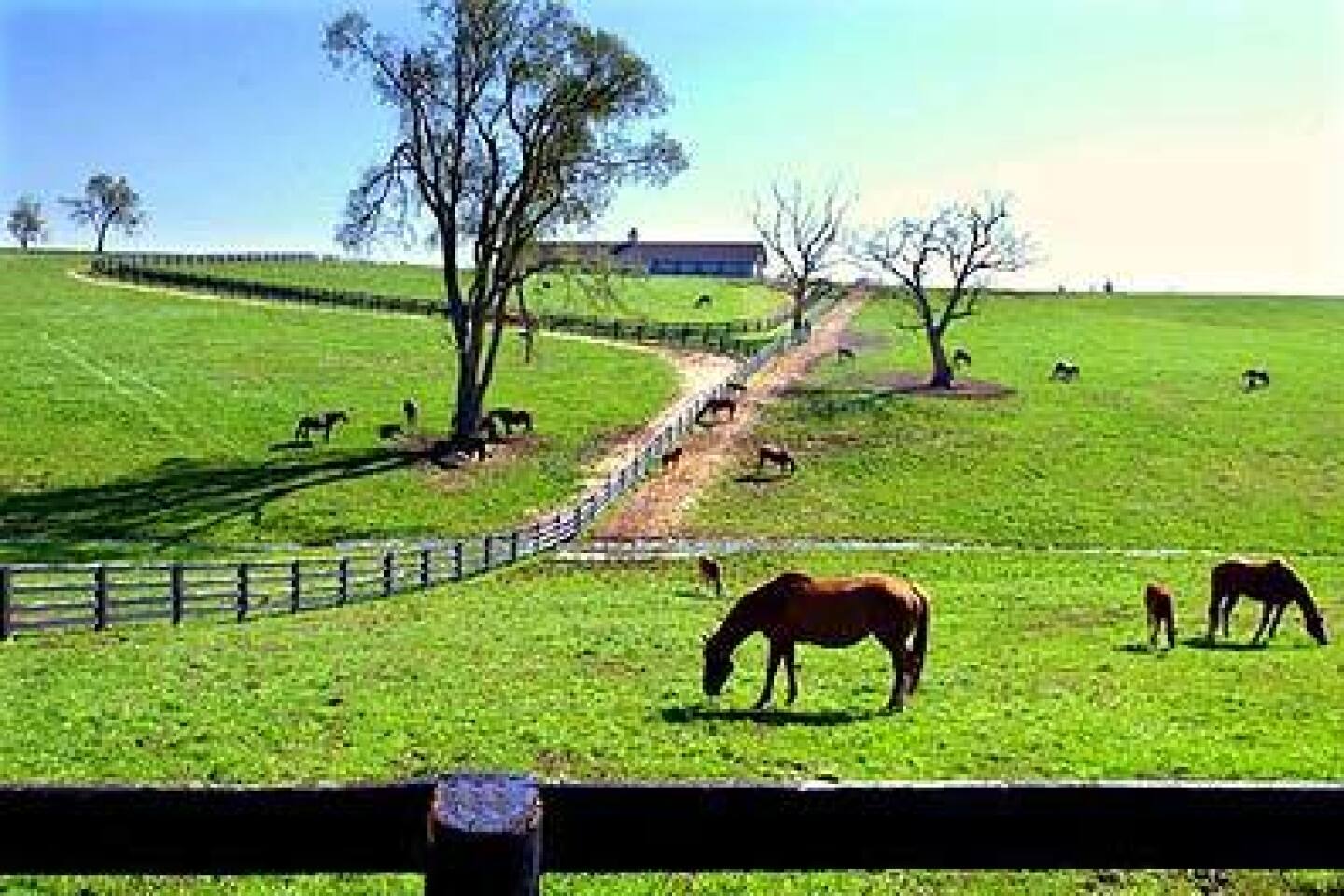

“We sometimes refer to it as wine country with stone fences,” said state tourism official Jayne McClew.

There are some differences: no vineyards, for instance. But there are lush, rolling hills, huge casks of spirits quietly aging in dark warehouses and fun tours that sometimes end with free tastings. And these samples are 40% to 60% alcohol or more, not wine’s paltry 5% to 13%.

That’s why I visited here a couple of weeks ago and happily sipped my way around bourbon country in the Bluegrass State -- taking care, of course, not to sip and drive. In the process, I learned a lot about the whiskey called bourbon, the down-home folks who make it and the picturesque thoroughbred horse country of central Kentucky, where many of the distilleries are.

At the Jim Beam distillery in Clermont, I walked into the elegant Victorian house where tastings are held and found five young ad agency employees from Chicago grinning widely and holding thin crystal glasses up to the light. They were sniffing and swishing and tasting -- just as they would have at a winery.

“We’re just sipping mash and talking trash,” said one.

“Yowch,” bellowed another, surprised at the kick from the uncut, unfiltered Booker’s Bourbon, which is bottled at 121 to 127 proof (more than 60% alcohol).

Lately I’d been hearing more about bourbon, even before visiting Kentucky. The rich amber liquid, which began to fall out of favor during the ‘70s, is seeing an upswing in popularity, particularly in trendy bars and restaurants in America’s large cities. And it’s the expensive, premium bourbons -- ranging from $20 to $250 a bottle -- that are leading the charge.

“It’s definitely coming back into full fashion,” said Heather Simon, lead bartender at the Cameo in Santa Monica’s Viceroy Hotel. The bar’s top-selling bourbon drink is the Knob Creek Manhattan, which features a 9-year-old premium Jim Beam bourbon. In New York City at the boutique Time Hotel, Knob Creek is the primary ingredient in the bar’s popular Country Time Martini. At the Bellagio hotel and casino in Las Vegas, Maker’s Mark is ordered so frequently that it’s now “on the gun” and can be automatically dispensed by bartenders to save time.

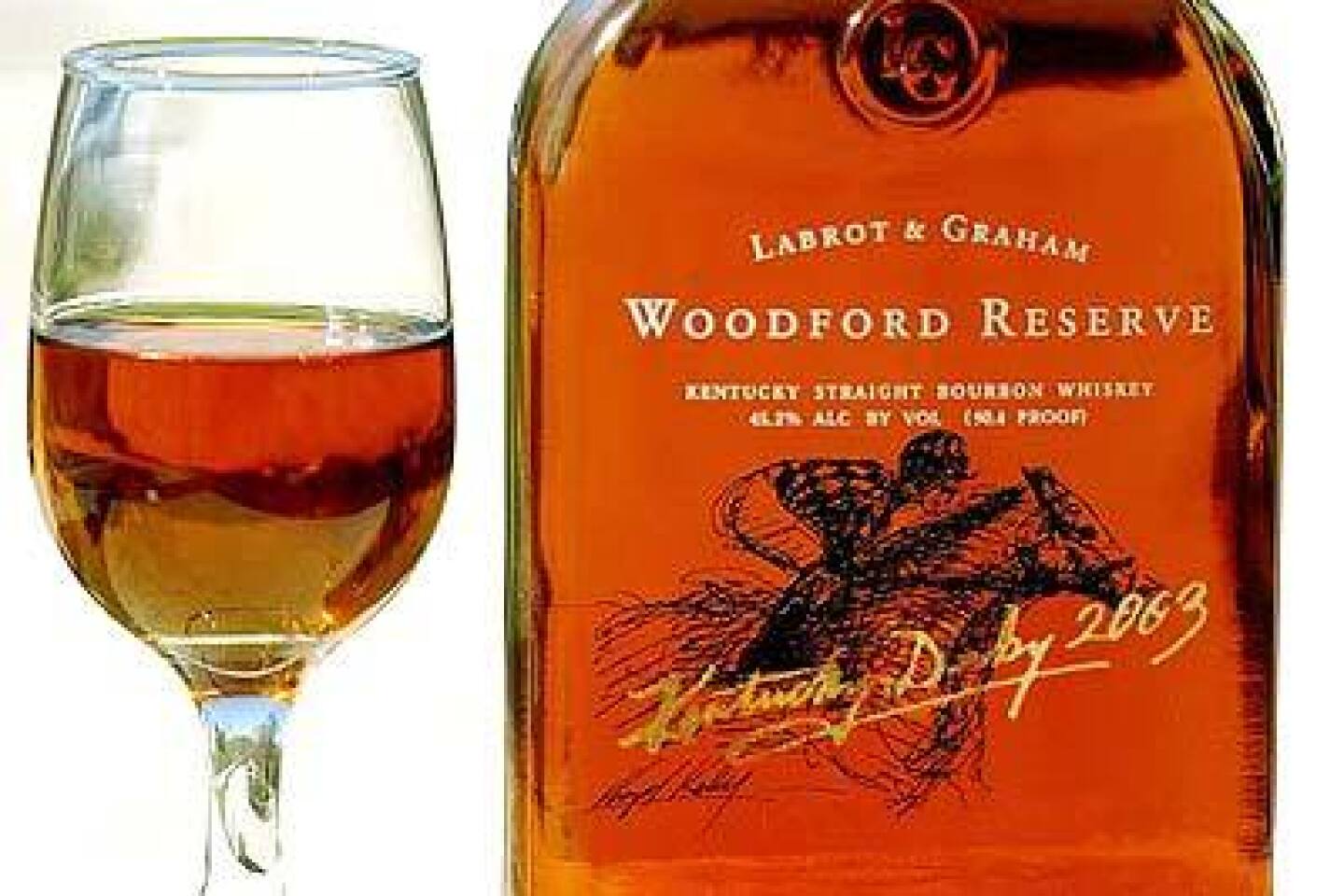

In Kentucky, bourbon drinking probably hits its peak on the first Saturday in May on Derby Day -- the Big Event of the year. The Kentucky Derby, May 3 this year, features three things the region is renowned for: fast horses, fine bourbon and blueblood families. More than 80,000 mint juleps, featuring premium Woodford Reserve bourbon, will be sold Derby weekend at Churchill Downs racetrack in Louisville (pronounced loo-ah-ville). It will also be poured in massive quantities in the richly furnished salons of old-line aristocrats, many of whom raise and race thoroughbreds, and in Millionaires Row, a reserved area of the grandstand where tickets are selling for $4,000 to $5,500 each.

But Kentucky is a state of many contradictions. While it makes more than 90% of the world’s bourbon, the whiskey can be sold in fewer than half its 120 counties. The rest are dry, meaning alcohol sales are not allowed.

“Most of Kentucky’s still living in Prohibition,” drawled Jimmy Russell, the man behind the Wild Turkey brand, when I stopped by his distillery, high on a hill overlooking the Kentucky River in Lawrenceburg.

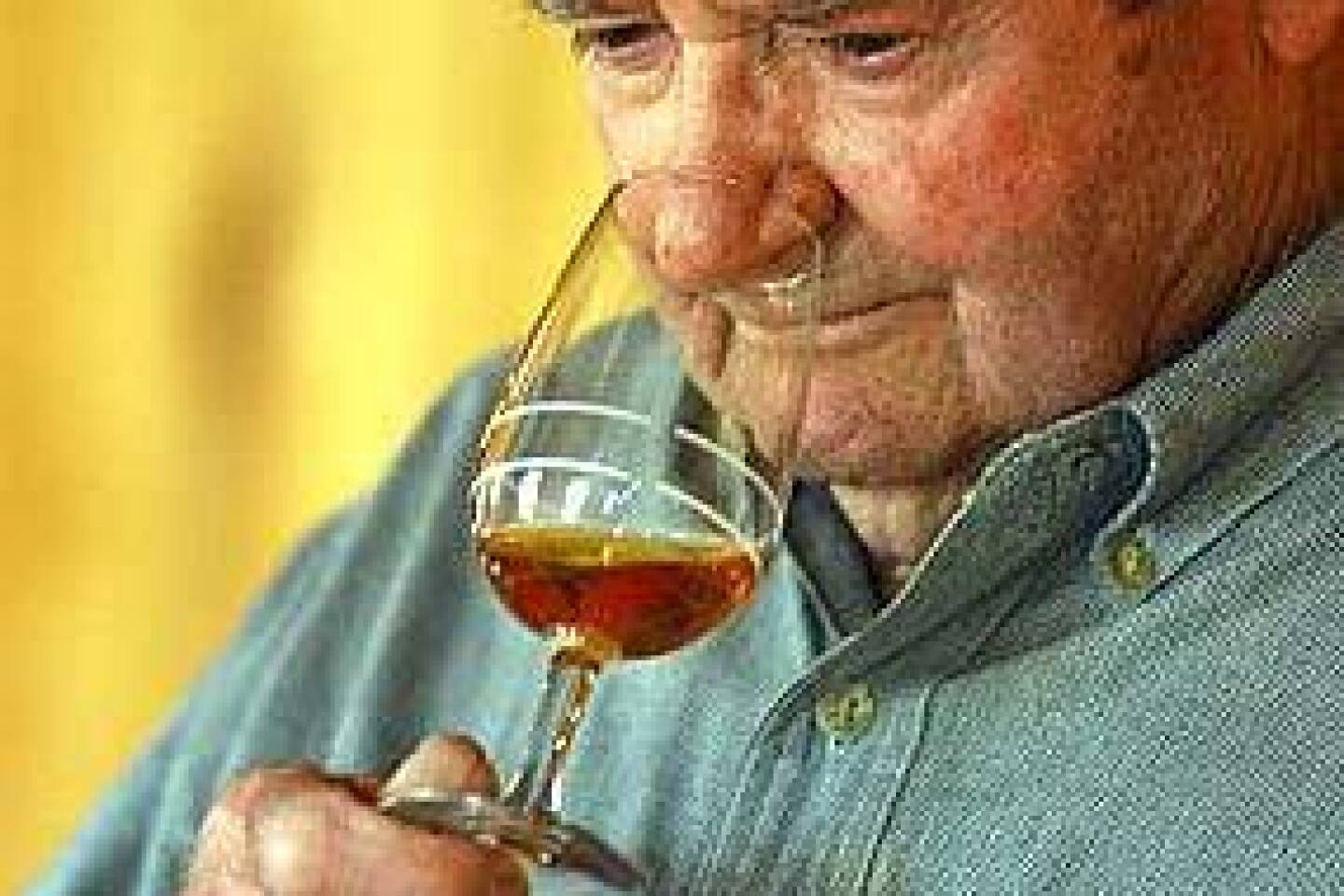

Russell, 68, is the master distiller, the man responsible for quality. Like the Wild Turkey motto -- “Not the latest thing, the genuine thing” -- Russell is the genuine thing. An affable, aw-shucks sort of guy, he’s as likely to lead a distillery tour as he is to sit behind a desk.

“This is the last place for 100 miles that you can find a bar or a restaurant that serves liquor. You know why? Southern Baptists and bootleggers. And neither of them wants the law to change,” Russell said.

Wild Turkey’s tour takes visitors into the buildings where fermenting vats and stills turn grains -- corn, rye and barley -- into “white dog,” a clear, uncut, unaged liquid similar to the moonshine still made in parts of the Kentucky hills.

“Here, taste this,” Russell said, handing me a glass. Was that a touch of a grin I saw?

“Ha, your face is puckering up,” he said as my eyes began to water and my knees began to knock. “Burns all the way down, doesn’t it? Makes my toes get warm,” he said gleefully.

This is a man who really appreciates his work: “What better job could there be than to come to work and taste bourbon every day?” he asked, his face beaming with pleasure.

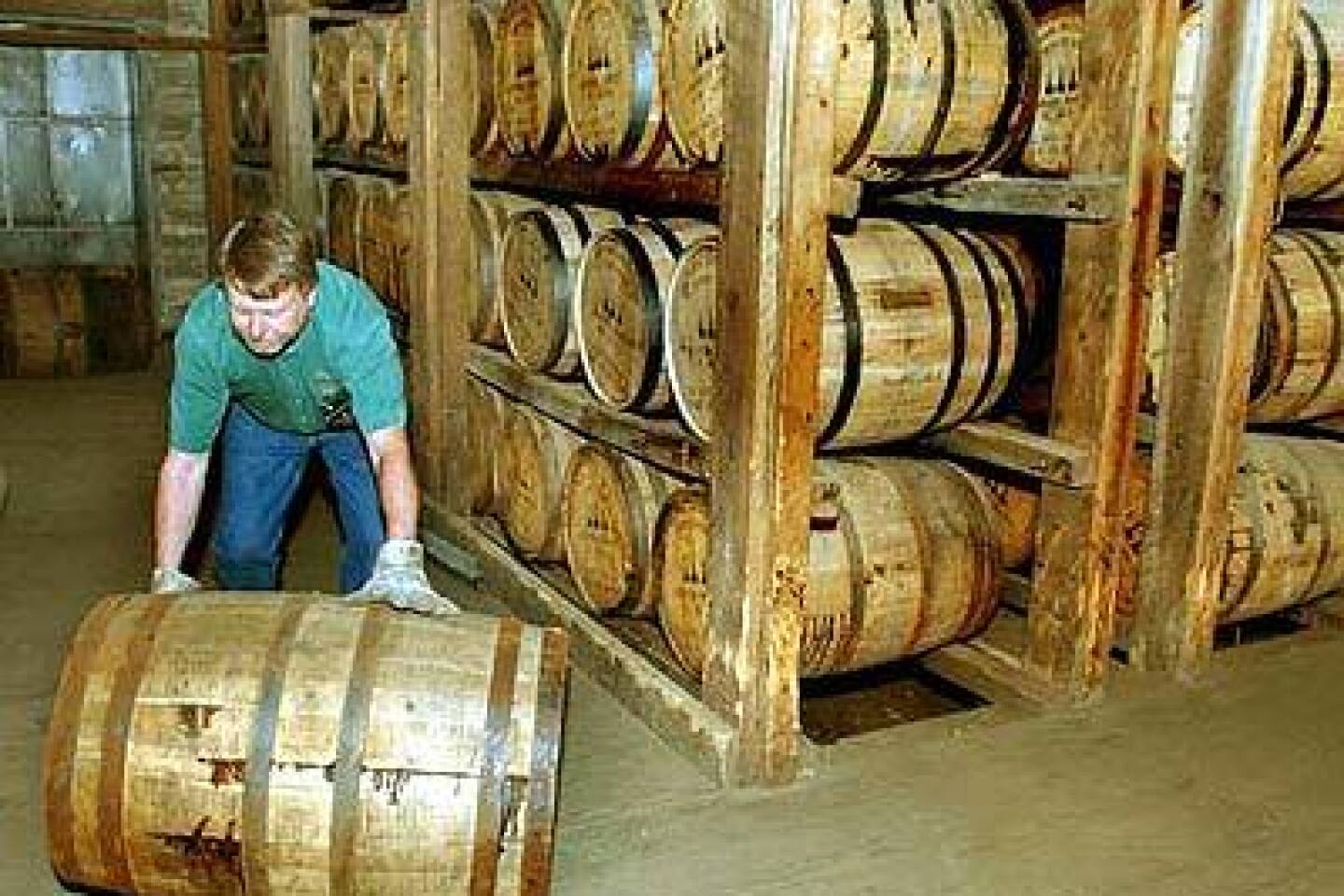

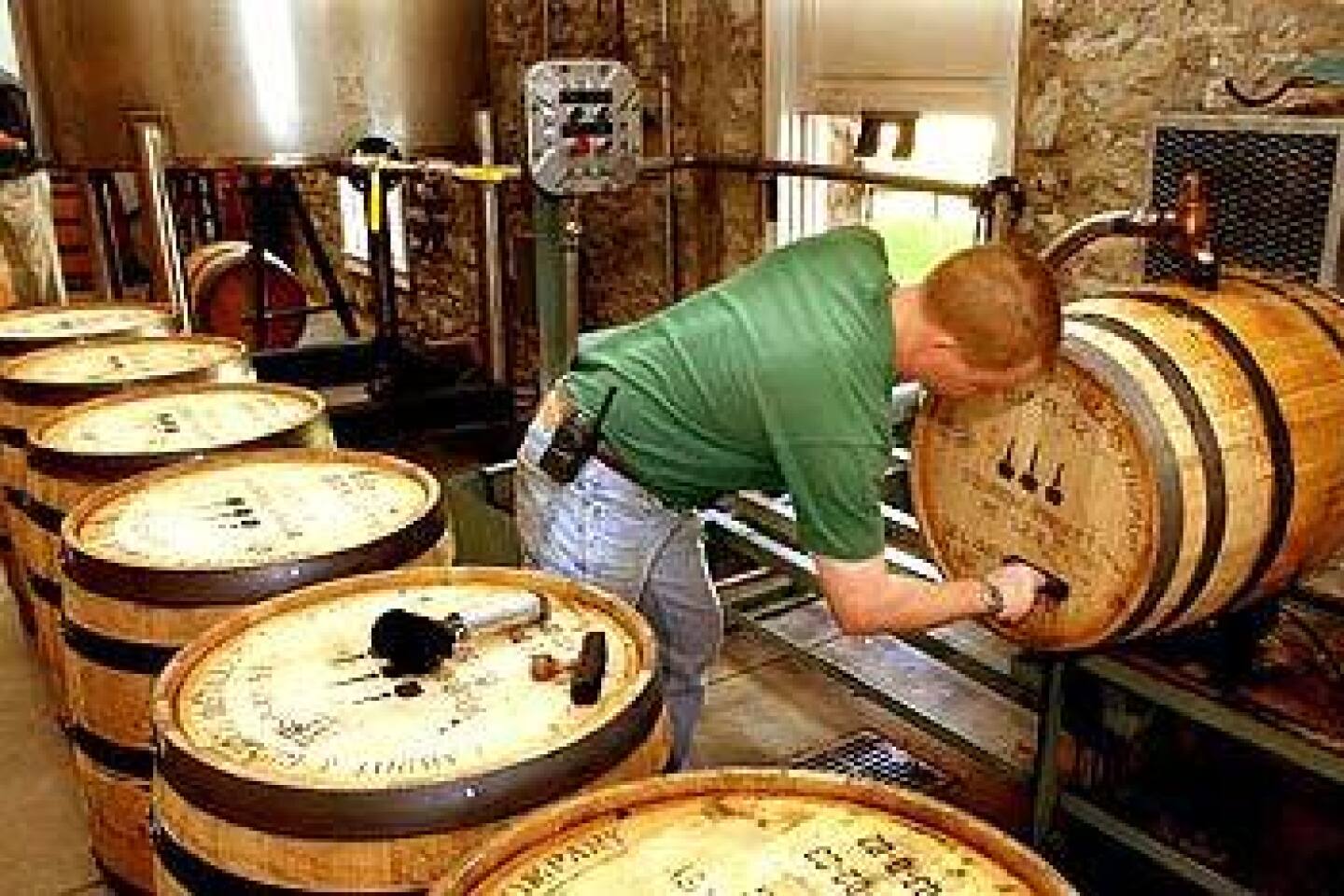

After distilling, the clear liquid is put into new white-oak barrels and stored in warehouses to age. The barrels are charred on the inside, giving bourbon its color and much of its flavor. My favorite part of each tour -- I managed to visit five of the seven distilleries on the trail -- was standing in the warehouses and breathing the rich, heady aroma of aging bourbon.

Making a name for itself

Named after Bourbon County, Ky., the beverage provided one of the state’s first industries, and it is made much as it was 200 years ago. But it differs from its cousins, Scotch and Irish whiskey.

“Every bourbon is a whiskey, but not all whiskeys are bourbons,” said Russell, explaining that by law bourbon must be made of 51% corn. It also must be made in the United States, distilled at 160 proof or less and aged at least two years.

The more I learned about bourbon, the more I wanted to know.

I headed back to my Louisville hotel, the Seelbach Hilton, and asked for a bourbon-tasting session. It’s a $16 investment but worth every penny. I took along a Kentucky cousin, Carla Brawner, whose father was once a distillery taster. (Yes, that’s right. I have bourbon in my blood.)

Jerry Slater, maitre d’ at the hotel’s Oakroom restaurant, obliged us. He’s a graduate of Whiskey Academy at Woodford Reserve’s Labrot & Graham Distillery. It’s a two-day class that teaches an appreciation for the subtleties of whiskey, particularly bourbon.

Slater slid four bottles of premium bourbons onto the polished oak bar: Wild Turkey Russell’s Reserve (10 years old, 101 proof), George T. Stagg (15 years old, 137.6 proof), Elijah Craig (18 years old, 90 proof) and Pappy Van Winkle (20 years, 90.4 proof).

Would we be able to tell the difference increased aging makes? Would we recognize the various proofs?

Would we be able to walk and talk when we were done?

As we sipped and compared, we discussed the elegant 100-year-old Seelbach hotel, which has a bourbon history all its own. Legend has it that F. Scott Fitzgerald was thrown out three times for drunken behavior. He apparently spent enough time here, however, to use the hotel’s Grand Ballroom as the setting for Daisy and Tom’s wedding in “The Great Gatsby.” Chicago mobster Al Capone was another frequent guest. I wondered aloud if he’d ever sipped bourbon here.

“Undoubtedly,” Slater said, switching back to the subject at hand. He was holding up a bottle with a familiar bird logo. “You know the ad that says, ‘It’s not your father’s Oldsmobile?’ ” he asked, pouring each of us a small amount of Wild Turkey Russell’s Reserve. “Well, this isn’t your father’s Wild Turkey. Its flavor is very concentrated. There’s sweetness and a vanilla taste.”

We followed his lead, sniffing a bit, then sipping the premium bourbon. It tasted good, but I wasn’t sure I grasped the nuances. We pressed on, sampling the four fine bourbons, ending with the high-powered George T. Stagg, uncut, unfiltered and nearly 70% alcohol. Again, my face puckered.

Slater didn’t wait for a comment. “If it’s too strong, cut it back with water or ice. The important thing is that you get it to the point where you like it. When you do that, it’s smooth and wonderful.”

It was helpful advice, but I was starting to feel that I was spending too much time indoors with a glass in my hand. It was time to take a break from bourbon and concentrate on another of Kentucky’s pleasures: its horses.

My first stop the next day was at Churchill Downs racetrack for a peek inside the Derby Museum, billed as the “world’s largest equine museum.” In addition to horse and racing displays, visitors can see a lively film, aired on a 360-degree screen, that places them in the center of Derby Day action, then take a walking tour of the grounds.

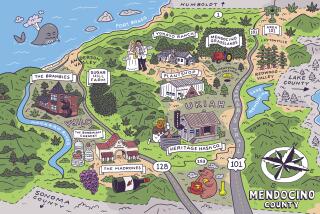

From there I headed southeast toward Lexington, where horse farms and beautiful country estates have been part of the scenery since the region was settled in 1775. Near town, I stopped at the Kentucky Horse Park, where there are daily horse shows and a self-guided farm tour. Then I rambled off the main highway onto country lanes. They were inviting: rolling hills strung with white or black fences, mares and foals frisking across green fields, palatial estates visible from the road.

I’d been impressed with the low cost of living when I arrived in Kentucky: The median gas price is $1.56 per gallon, and the median home resale price in Louisville is $118,600. But in horse country, homes worth more than a million dollars are common, although this price typically includes much more land and square footage than is found in similarly priced West Coast homes.

No visit to the bluegrass region, named for the tint of the grass, is complete without a stop at a horse farm. I chose Ashford Farm in Versailles (Kentuckians pronounce it ver-sales), where Derby winners Fusaichi Pegasus (2000) and Thunder Gulch (1995) are among the resident stallions. They are the glamour boys of the industry, living in stables with polished oak walls and chandeliers and walking on rubberized mats to reduce the chance of a fall. During mating season, “they’re busy boys,” said groom Larry Anthony. “They have dates as many as four times a day: 7:30, 1:30, 6 and 10.”

They’re paid well for their efforts too. The dark bay Fusaichi Pegasus earns $125,000 for each successful mating. “But he cost $68 million,” Anthony said.

Many of the horse farms in the region -- there are about 450 -- welcome visitors. But it’s important to call ahead, book a visit with a guided tour group or hire a private guide. Just around the corner from Ashford Farm I found the picturesque Woodford Reserve’s Labrot & Graham Distillery in a scenic hollow on Glenn’s Creek. Whiskey has been made on the site since 1812.

At the end of the tour, peach tea and bourbon balls were waiting. “No Woodford Reserve?” I asked.

“We’re not geared up [for sampling] yet,” I was told. The Kentucky Legislature approved sampling at distilleries in 1998, but not all have implemented it.

Down the road in Frankfort, Buffalo Trace (formerly Ancient Age) Distillery serves two samples to its visitors. The distillery is in town and is more industrial looking than its competitors. But bourbon accompanies the bourbon balls at the end of the tour.

Elmer T. Lee, master distiller emeritus, wandered over as I joined other tourists for a taste. At 83, Lee is the oldest master in the industry. He tried to retire in 1986, but he keeps showing up for work.

Has the industry changed much in the 53 years he’s been involved?

“We’re making better bourbons than we did 50 years ago,” he said. “Today’s sophisticated instruments help us control the product better.”

At every stop I learned a little more, but I still wasn’t sure I had captured bourbon’s essence.

At Happy Hollow Road in Clermont, the home of Jim Beam, things became a bit clearer. I visited the distillery with Kentucky cousin Ed Kuffner, another member of the bourbon-tasting branch of the family. We missed colorful Booker Noe, the sixth-generation Beam family member who acts as master distiller emeritus, but we did run into master distiller Jerry Dalton. He joined us in the tasting room, talked about some of the company’s premium bourbons -- including Distiller’s Masterpiece, which retails for $225 to $295 a bottle -- and gave us some pointers.

“If you’re going to get unconscious, buy the cheapest bourbon you can find. If you’re going to appreciate the process, learn as much as you can. And taste as much as you can.”

Sounds like good advice to me.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.