National World War I Museum in Kansas City, Mo., gets personal

As my husband, Toby, and I climbed the wet stone steps to the knoll where the towering Liberty Memorial has stood sentry for nearly nine decades, our heads were bowed in a vain attempt to avoid the drizzle of an unseasonably cold April morning.

The gray mist hanging over the downtown skyline was a fitting backdrop for this visit to the National World War I Museum at Liberty Memorial, honoring the 67 million men and women from 36 countries who had served in the Great War.

This museum, the only one on U.S. soil dedicated to preserving the history of the War to End All Wars (which, unfortunately, turned out not to be true), is an extraordinary place to be reminded and will be especially so during the next four years of centennial exhibitions and events.

After the fighting ceased in 1918, Kansas City civic leaders raised an astonishing $2.5 million in just a few weeks to erect a monument to honor the war’s living and dead. A national architectural design contest was conducted, and organizers chose a hilltop site across from the majestic Union Station, which had opened in 1914, the same year the war started.

On Armistice Day 1926, the grand dedication of the 217-foot memorial tower; two stone sphinxes, named “Memory” and “Future”; and two exhibition buildings drew 100,000 people, including President Coolidge.

Organizers had begun to collect artifacts — most donated by soldiers and their families — almost immediately after the war and eventually amassed what’s considered the world’s most diverse collection representing all countries involved in the war.

In the late 1990s, plans were set in motion to restore the memorial and build a large underground museum. Congress christened it the country’s official National World War I Museum in 2004; the site earned National Historic Landmark status and the doors to the 50,000-square-foot museum and research center opened in 2006

The Liberty Memorial towers above a broad deck and grassy mall that lead to the museum’s entrance. Save for a skylight with a glimpse of the tower, there are no windows in the museum, and the large, heavy entrance doors close with a firm finality behind those who enter.

Once inside, a glass bridge into the exhibition area spans a mud field planted with 9,000 poppies. Each red flower represents 1,000 combat casualties from the war, but even with the visual aid, 9 million deaths are nearly impossible to comprehend.

The introductory film, “A World on the Edge,” offers a stirring orientation to the boiling pot that was the European prewar era with its growing industrialization, job shortages and monarchies with unprecedented power. Current-day parallels (only the country names have changed) are unmistakable: Militias were growing, Germany was aggressively expanding and there were rising tensions in the Balkans.

The war’s first year is being examined in greater detail in special exhibitions in the two original buildings. Over the next four years, additional exhibitions mirroring what was happening a century ago will showcase artifacts usually not on display.

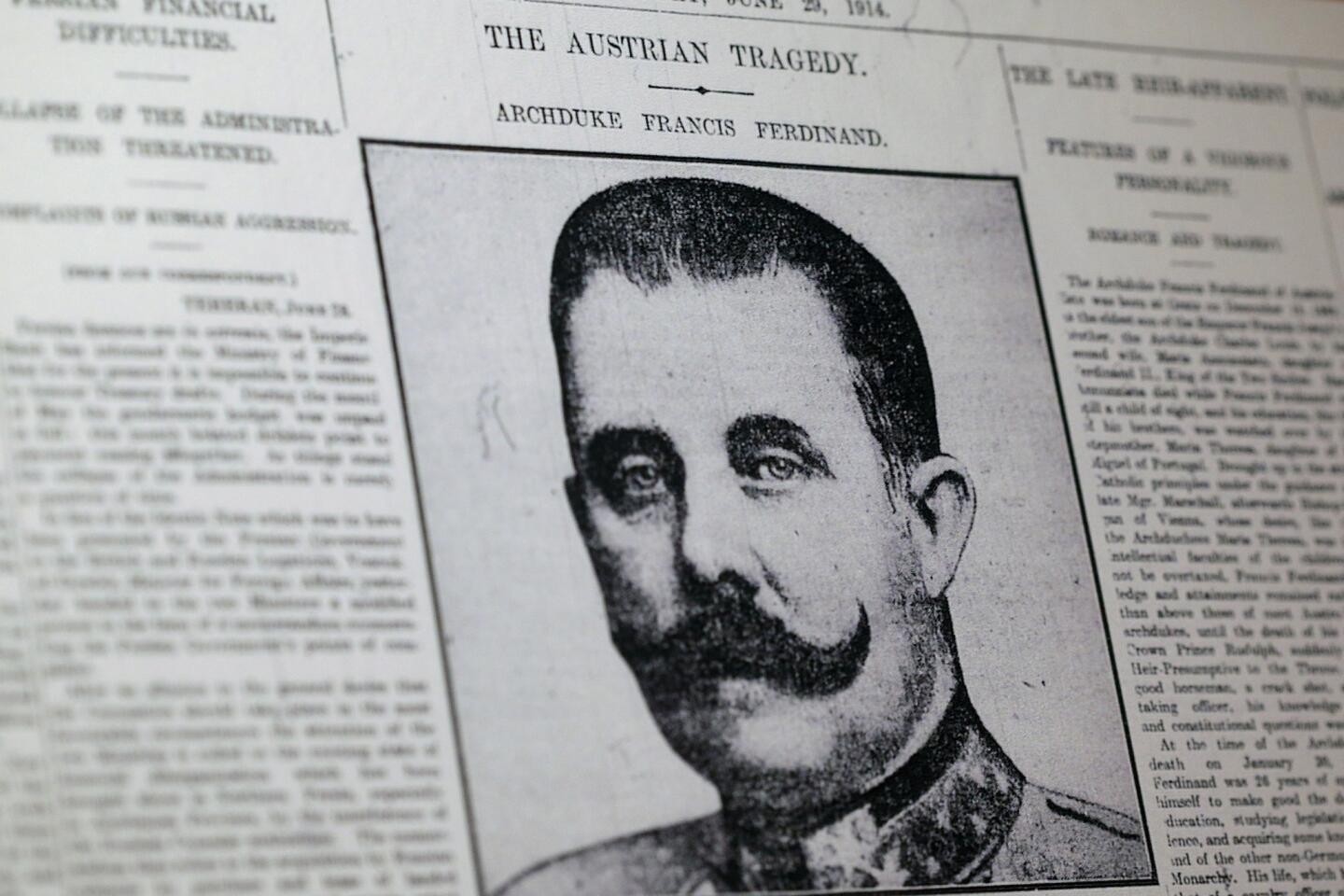

On view until Sept. 14 is “On the Brink: A Month That Changed the World,” which examines what happened on June 28, 1914, when a teen assassin killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A month later, on July 28, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and a week later Russia, France and Britain mobilized in support of Serbia and were at war against Austria-Hungary and Germany.

The particularly haunting exhibition, “Over by Christmas: August-December 1914,” will be on view through March 29 with displays of the elaborate flags, ornate swords and colorful but impractical uniforms and spiked helmets troops confidently marched off to war with, fully expecting to be home in time for the holidays.

The first half of the main museum covers the years 1914 to 1917. At the museum’s midway point a second film, projected on a panoramic screen above a life-size tableau depicting a muddy wasteland, looks at the factors that tipped the United States into the war and introduces the second half of the museum.

Throughout, graphics and timelines clearly relate such pivotal events as the sinking of the Lusitania passenger ship by a German submarine and staggering statistics such as that one in three French men died in the war effort. A world map shows the complicated relationships of the three dozen countries that eventually declared war on one or more countries.

Although the vintage aircraft, French-made Renault tank and Ford Model T ambulance command attention, the heart of the museum is in such achingly personal items as a tiny pocket diary, Western Union telegrams, painstakingly illustrated envelopes carrying letters to a soldier and a hand-painted sign with an arrow that says “Walking Wounded.” Propaganda posters, including the first ones featuring the newly created Uncle Sam, line the walls alongside newspaper accounts, photographs, weapons and uniforms from various countries.

My husband and I took in as much as we could and then retreated to one of several private reflection rooms where we sat listening to music of the era: Popular tunes such as George M. Cohan’s “Over There” and John Philip Sousa’s “Liberty Loan” march brought home how all-consuming the war had been for our grandparents’ generation.

I could not help but recall Edmund Burke’s remark that those who do not know history were destined to repeat it. Without speaking, we departed through the heavy front doors. The rain had subsided but the sun had not yet broken through the clouds. Fitting weather for a day to remember.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.