In the shadow of celebrities and soldiers

One of the first signs that we were on an Army base was this posting on the path that leads to the Hacienda Guest Lodge: “You are entering a no-hat, no-salute area.”

The second came on our first morning here, the kind of day that only California can deliver. Songbirds warbled. The mist had lifted, and the sun was warm on my face as I sat on a rough-hewn bench under a portico at the 18th century San Antonio de Padua Mission, not far from the lodge. Then came the rat-a-tat-tat of machine-gun fire.

This land in the hills west of Paso Robles in Monterey County is one of the loveliest pieces of real estate in California, and the Army owns it. If you can ignore some trivialities -- parking lots of Humvees, Jeeps, tanks and camouflaged trucks, the sound of gunfire from soldiers’ practice sessions, some lapses in service and a slight shabbiness at the lodge -- it’s an interesting place to spend a weekend.

What drew us to this remote stretch of Central California was the 14-room Hacienda Guest Lodge and the chance to sleep where millionaire publisher William Randolph Hearst and his movie star friends once did. This was Hearst’s hunting lodge, built mostly for entertainment so he and his guests could ride on horseback the 30-odd miles from his San Simeon estate to spend a night or a weekend. It was designed by Julia Morgan, the celebrated architect of San Simeon, and completed in 1936.

Like Hearst’s guests, my husband, Barry, and I were here for the weekend, but we arrived not by private plane or horseback but by car after a 250-mile drive from Los Angeles through Friday evening traffic. After we were cleared to enter at the barricaded checkpoint, we picked up our key from a waitress in the Hacienda’s restaurant, there being no readily identifiable reception area.

Spacious but spare

I was told, when I reserved a room in the two-story lodge, that we would have a suite; at $125 a night it was the only room available and the most expensive. But I wasn’t prepared for the palatial size of our first-floor accommodations. It had a nicely appointed sitting room with a lovely arched brick fireplace, a large foyer, a full-size, fully equipped kitchen, two bathrooms and three bedrooms laid out one after another, like connecting rail cars. It felt cavernous for just two of us but would have been ideal for a family.

The bedrooms were cold and their décor spare -- bed, alarm clock, lamp on a night table and space heater in a corner -- so we spent most of our time in the heated sitting room, even sleeping there. It was almost Baroque by comparison, with a floral print couch, two comfortable armchairs, books inside a barrister’s bookcase and a TV (which had no reception) with a VCR. (Videos were available in the dining room.) There were some charming period pieces, such as a Depression glass vase, and some comforting touches, like a heater in the bathroom. But there was a shabbiness too: a loose towel bar in the bathroom, a hole in the ceiling, a dirty and uninviting swimming pool.

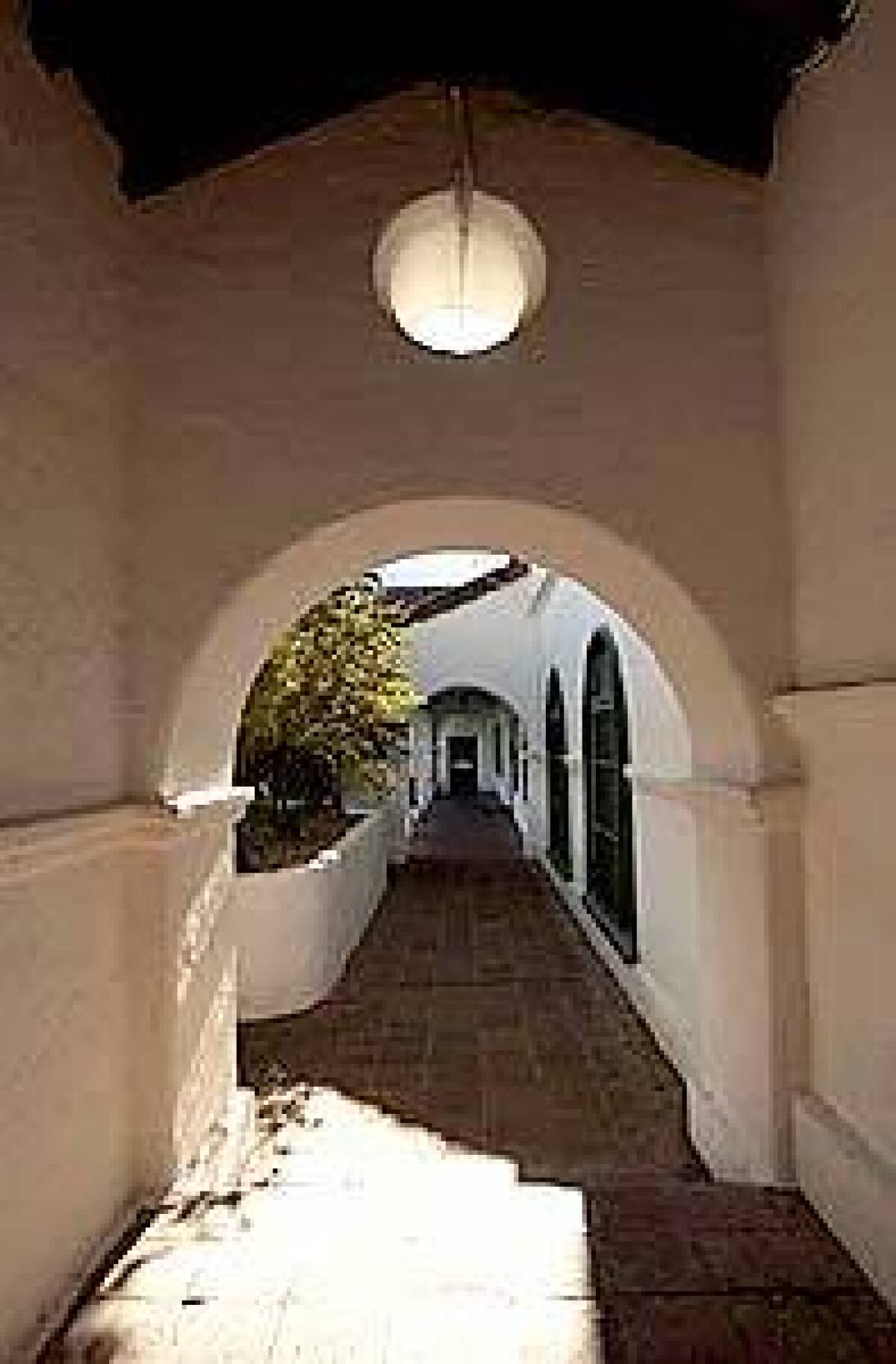

Outside, Morgan’s graceful creation echoes the nearby mission. The concrete-reinforced Spanish-style lodge has a U-shaped courtyard, quatrefoil windows, colonnades with windows that look out on the golden hills of the Santa Lucia range, arches and high ceilings.

After the Army bought the property from Hearst in 1940, it altered Morgan’s structure. Some changes were necessary, like adding electricity; some were decorative, like the murals that adorn the dining room and bar. Some would make Morgan devotees cringe, like changing the symmetry of her original design by closing off an archway and blocking the curved stairway that led to the second-floor Tower Room. Hearst slept in this room with the gold-painted dome. It’s the best at the lodge, a worker told me, but it was occupied, so I couldn’t peek in. We did look at a tiny room on the second floor. With lovely arched and carved wood doors and latticework, it was more atmospheric than our suite.

We woke Saturday morning, expecting to have breakfast in the dining room, but it was closed until 11 a.m. As I sat there grumping about being in the middle of nowhere with no food, drinking the Sanka with powdered cream that we had found in our suite’s kitchen, I was glad we’d had the foresight to indulge the previous night in a five-course French meal at Bistro Laurent in Paso Robles. The restaurant impressed us with its excellent service and food, which included entrees of rack of lamb and sea bass.

After Barry offered me the bowl of papier-mâché fruit to boost my spirits, we went to the mission, the third in the state, dedicated in 1771 by Father Junípero Serra. Its adobe lines were calming, except for the occasional burst of machine-gun fire, and the interior of the church was warm with pastel colors and the scent of votives. We spent an hour here before hunger sent us foraging for food outside the Army base.

We found some pre-packaged sandwiches and chips at the Lockwood General Store a few miles east of the base and decided to picnic by the shores of Lake Nacimiento. We paid $10 to sit by the lake, eating sodden sandwiches, at the privately owned resort listening to the whine of powerboats navigate drought-shrunken waters.

But I was cheered by the drive on Monterey County Road G14, which delivered a quintessential California landscape: golden hills dotted with the rounded green canopies of live oaks, all free. (We also ran into fist-size tarantulas crossing the roads.)

The toast of the county

We were on the edge of Paso Robles’ wine country, so we took a detour down oak-shaded lanes to Carmody-McKnight, a tiny vineyard that’s known for its Zinfandel-like Cabernet Franc. We left toting a bottle and a recommendation to try Pipestone, a new vineyard about 10 miles east on country roads.

At Pipestone, I found the pastoral scene I was seeking. Grapes hung low on the vines, and a fountain splashed quietly.

Our last winery stop offered something for each of us: For Barry there were the Bonny Doon wines. For me there was Sycamore Farms, an herb nursery next door. Barry came away with a bottle of Big House Red, and I had a wagonload of plants.

After a stop to pick up groceries for the next day’s breakfast, we made it back to the Hacienda for cocktails as the sun was setting. The bar has lovely bones but looks as though it’s had a few too many rough nights. The blare from the jukebox and the smell of stale liquor drove us out to the expanse of lawn in front of the Hacienda, which had a panoramic view of fields and hills. Sitting on the lawn, I could imagine Hearst, Marion Davies, Clark Gable and Carole Lombard enjoying the same sight.

Our dinner of filet mignon and a hamburger at the restaurant was far better than our lunch, and we left feeling satiated for the first time that day. (The kitchen does fried and grilled food well.) We retreated to our parlor, where I fell asleep and Barry settled into an armchair with a book.

Someone must have heard the rumblings and grumblings of my stomach the day before. On Sunday morning we found two Danishes among the packets of Sanka and tea, and we added them to the English muffins we had bought the day before for our breakfast.

For our return, we chose the route Hearst might have taken: curving Nacimiento-Fergusson Road to the Pacific Coast Highway north of San Simeon. It turned out to be another of the wonderfully scenic drives we happened on that weekend: Trees in Los Padres National Forest wore the colors of autumn -- a yellowing maple, the bright reds of poison oak -- and the coastal fog that crept up the hillside created a Zen-like beauty.

We sped down PCH, past San Simeon, its towers gleaming on the hill. The Hacienda was no enchanted castle, but it was close enough for government work.

Vani Rangachar is an editor in the Travel section.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.