Gettysburg 150th: A historic battle, an amazing town

GETTYSBURG, Pa. — You know the story of the Battle of Gettysburg. You know that the two sides met on a 9-square-mile battlefield in the Cumberland Valley of Pennsylvania, and you know that for three days in July 1863 cannons boomed and guns fired and soldiers died by the score and that, in the end, the Union triumphed and sent the South scurrying home.

If that battle launched the town of Gettysburg onto the national stage, it is its aftermath that has kept it there — and has kept it from becoming more than just a dusty repository of history. Some will say it is overtouristed and point to the tattoo parlors and the cupcake stores. Unless you have a hankering for ink or sugar, they’re easily overshadowed by one of the most amazing towns in America.

I probably wouldn’t have said that before a recent visit, but I had forgotten. As a junior high student in northern Virginia, I was required, along with the rest of my squirmy classmates, to make the 125-mile trek to the town that’s just a hair over the Maryland border. For me, a big battle probably translated into a big bore.

Today, Gettysburg has many more ways to tell the story of the three days that changed history. The visitor center, opened in 2008, hosts the restored Cyclorama painting, a film narrated by Morgan Freeman and a museum of diverse artifacts. Gettysburg’s Town Guides offer walking tours on a host of topics, and private battlefield tour guides can drive while you gawk and learn. And the Seminary Ridge Museum, which is set to open Monday, helps put what you have seen and learned into perspective.

That history made human, plus a plethora of books and maps, helped me understand more fully how the ugliness of the battle that shaped the town should give rise to any country’s prayer for peace. Here are some of the surprises and highlights of a visit here, in the Battle of Gettysburg’s sesquicentennial year.

Gettysburg was an accidental battlefield. It’s often said that Gettysburg was a target because Southern troops needed shoes. By 1863, the South was feeling the pinch of war, and some supplies were scarce. That lends credence to the notion that Confederate Maj. Gen. Henry Heth detoured to Gettysburg in search of footwear for his troops.

Some historians dismiss that idea. Today, if you drive through Adams County, of which Gettysburg is the county seat, you’ll see acres and acres of farmland — about half the county, in fact, producing about $200 million in agricultural products.

And so it was in the 1800s, which explains why maps of the battle are often marked with such names as Peach Orchard, Plum Run and Wheatfield.

Agriculture, not shoe manufacturing, was the economic engine. In “Hallowed Ground,” James McPherson writes that the “22 shoemakers listed in the 1860 census … were barely sufficient to make or repair the footwear worn by county residents.”

What is certain is that Gen. Robert E. Lee was ready to invade the North, having scored psychological and military victories. Neither side was completely sure where the other was, but Heth’s troops ran into Union cavalry led by Gen. John Buford, and the ensuing skirmish set the stage.

It’s not what you know; it’s whom you know. A statue of Gen. G.K. Warren peers down from Little Round Top, a strategic position for the Union that his actions helped to save. Warren realized that one corps of men was out of position. Its leader, Gen. Daniel Sickles, a onetime congressman from New York, had decided he knew better than Gen. George Meade, who was leading the Union troops. (Gen. Ulysses Grant was in Vicksburg, Miss.)

Warren called Sickles’ maneuver to Meade’s attention. To this day, some will argue that Sickles’ decision to move men wasn’t the wrong one; his insubordination was. And I swear that Warren’s eyes have a trace of “What … was he thinking?”

Sickles was never disciplined. Indeed, wounded later in the battle, he was visited by Abraham Lincoln and eventually awarded the Medal of Honor. Keep in mind that Sickles was a politician and that he had once successfully defended himself on a murder charge by claiming insanity.

What happened to Warren seems just as lunatic: The Hero of Little Round Top was later relieved of his command by Gen. Philip Sheridan at the Battle of Five Forks, near Petersburg, Va., just before the end of the war. Sheridan was dissatisfied with Warren’s performance, but he didn’t disobey any commands, as Sickles had. It ruined Warren’s career. He was exonerated ultimately — after his death. Some say Sickles’ connections kept him from the fate that befell Warren, proving, once again, that all is not fair in war.

Warren’s bravery at Little Round Top helped the Union hold on Day 2. By Day 3, the South’s disastrous Pickett’s Charge, led by Gen. George Pickett, failed, and Lee and his remaining men were forced to retreat.

The aftermath was as horrifying as the battle itself. The number of dead — more than 7,000 — was only part of the problem. More than 20,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were wounded. Gettysburg was a town of about 2,400, and suddenly it had to care for, feed and cure almost 10 times that number.

As you walk around town today, you’ll see numerous buildings marked with red flags signifying their use as hospitals. On a chilly May morning, I stood before Christ Lutheran Church and watched the red flag unfurl in a stiff breeze as guide Linda Seamon explained how every church in town — save one — became a hospital. The one that did not was a church for African Americans, which closed when they fled in terror.

Townspeople took in patients. One such volunteer was Sadie Bushman, who was living with her parents when the fighting broke out. She had charge of her younger brother, but they were separated from their parents for two long weeks and were presumed dead. What Sadie was doing in those two weeks — and continued to do after the family was reunited — was helping to tend the wounded.

She fed them, wiped their brows and even assisted at an amputation, which scared her, according to the Gettysburg Compiler of Jan. 12, 1892. Sadie was well-loved by the soldiers and surgeons, and her bravery was unquestionable. More so than others in town? Perhaps.

During her service to the sick, she was just a few weeks shy of her 10th birthday.

Meanwhile, there were the dead to cope with. Besides 7,000 dead soldiers, about 3,500 horses, mules and other animals were killed. The dead soldiers were hastily buried. Rains in subsequent days unburied them.

Accounts of the day describe the air of Gettysburg as heavy with the smell of putrefying flesh. The town hadn’t been prepared for a battle, and it certainly wasn’t prepared for the aftermath.

Pennsylvania Gov. Andrew Curtin, who arrived about a week after the battle, was horrified by conditions and appointed local lawyer David Wills to manage the situation.

Burial ground was purchased, and the Northern states became involved. Plans were drawn, and the dead eventually were laid to rest, but none of it happened quickly: It was more than four months before those grounds were consecrated.

And who would be the most fitting speaker for that task? Well, when you think of Gettysburg and addresses, you naturally think of Edward Everett. Don’t you?

Lincoln was a surprise speaker. As preparations were made for the ceremony, Everett was chosen as the keynote. The former governor of Massachusetts and president of Harvard was a natural choice; if he were alive today, he probably would be a speaker at a TED conference.

Lincoln was invited, but few people expected him to attend, given the press of business in Washington. When he RSVP’d yes, he was invited to give “a few appropriate remarks.”

He took them at their word, but it’s amazing he could concentrate.

The town was abuzz with news of Lincoln’s arrival and the dedication. There was not a room to be had on the night of Nov. 18, 1863.

Lincoln had a room, fortunately, in David Wills’ house. On Lincoln Square today, a Seward Johnson sculpture of Lincoln shows the president, standing with a modern-day figure, gesturing with his stovepipe hat toward the second story of the Wills house. That’s where Lincoln stayed, but he wasn’t the only guest.

The house was substantial but about three dozen people also were staying there; based on my tour, it wasn’t that substantial. Indeed, some guests had to share bedrooms and beds. At least Lincoln didn’t have to.

On a tour you can see the re-created room where the president slept and where he made final revisions. And you can wonder how Jennie Wills coped with this frenzy of activity: Her husband was trying to find a way to cope with the dead, her house suddenly was bulging with important guests, including the chief executive of the United States, and she had 38 dinner guests to feed. Never mind that she had three young children and was pregnant.

That’s the backdrop against which Lincoln made revisions to his address, of which five copies are known to exist. Lincoln, by the way, also was ill; he was thought to have a mild form of smallpox.

Lincoln’s speech was brief but brilliant and resounds with clarity today. The National Cemetery, south of town, is the resting place of more than 3,500 Union soldiers; a few Confederate soldiers were buried here by mistake, but the rest were disinterred and sent home, many not being reinterred until almost a decade after their deaths.

I heard Lincoln’s words, delivered here Nov. 19, 1863, in my mind’s ear as I peered at the gravestones.

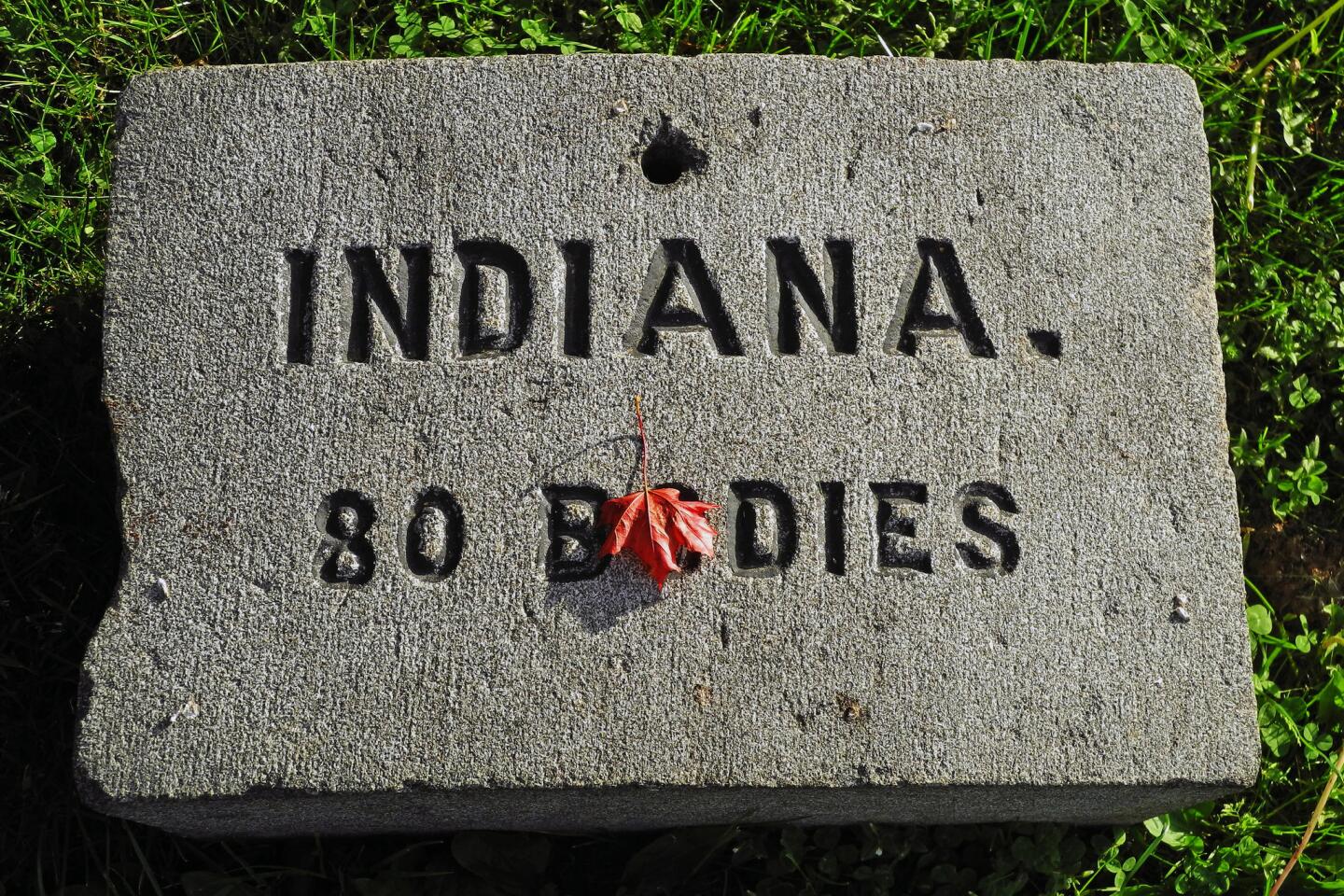

We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives. And the stones said: Indiana: 6 bodies. Delaware: 15 bodies. Unknown: 143 bodies.

That all men are created equal. And the stones said: E. Dennis; Lt. Christian Balder; George Smith; Capt. W.W. Harris; officers next to enlisted men.

The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. Everett said later in a letter to Lincoln, “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes.”

And that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the Earth. Five hundred thirteen days later, Lincoln was dead. Nearly 54,000 days after Lincoln’s death, this country is still alive.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.