Rockers, punks and cowboys find a rowdy haven at Cain’s in Tulsa, Okla.

Cain’s Ballroom, built in 1924 as a garage, is a national marvel among music venues. It has been presenting live music in Tulsa for close to a century, from country to punk and rap. This video tells what Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys did there, w

In the middle of a show at Cain’s Ballroom — when the maple floorboards are trembling, the neon star in the ceiling is gleaming and a high guitar note is bending toward bliss — you might suspect that the room was never intended for this.

You’d be right.

In 1924, before Bob Wills played his first dance at Cain’s, before Sid Vicious punched a hole in the wall, before artsy millennials started haunting the neighborhood, this broad brick building was supposed to be a garage or car dealership, owned by W. Tate Brady, a Tulsa founding father.

But Brady died. A dance instructor took over. The Depression hit. And the space was reborn as Cain’s — a great American music venue whose history of hope and hell-raising makes it a treasure.

You’ll find it in the Tulsa Arts District, across the railroad tracks from downtown’s Art Deco skyscrapers. Look for the red and white neon.

“When I walked through those front doors into this place, I got a chill,” Larry Shaeffer, the owner from 1976 to 2000, told me. “You could just feel that something great had happened here.”

For close to 90 years, the ballroom has housed dances, concerts, binges, brawls, mud-wrestling matches, a circus sideshow and one pig race. But its fame stems from 1935, when drought and dust storms began to assault large parts of Oklahoma, Arkansas and Texas.

Long-ago music stars

That year, a fiddle player named Bob Wills and his Texas Playboys band showed up and started playing — a free lunchtime show every weekday, plus dances Thursday and Saturday nights, all broadcast live throughout the West on KVOO-AM radio.

“He was the Elvis of his time,” said John Wooley, a Tulsa journalist and author who has co-written a history of Cain’s, so far unpublished. “When Bob walked onto the stage, everything was transformed.”

With a cowboy hat tilted on his head and a cigar clenched in his teeth, Wills (1905-1975) specialized in Western swing, an upbeat, dance-friendly genre that has elements of pop, jazz and blues.

“San Antonio Rose” was a Wills tune. “Take Me Back to Tulsa” was another.

Workers used to bring their sack lunches to the weekday shows. Tulsans say you could walk down the street and hear the Playboys on the radio in every home.

“Every day, he broadcast hope,” said Jeffrey Moore, executive director of the soon-to-open Oklahoma Museum of Popular Culture. “And it really became the soundtrack for people’s lives during this very difficult time of American history.”

The shows continued for about seven years, until the U.S. entered World War II and Wills headed to California.

“Merle Haggard told me the [radio] signal would come into Bakersfield,” Shaeffer said.

Though Tulsa was heavily segregated in those years, Wooley said, Cain’s owners regularly rented the building to promoters of African American musicians, including pianist and bandleader Count Basie and saxophonist Clarence Love, who played to black audiences.

On other nights, Wooley said, Wills and company joined after-hours jam sessions with black blues and jazz performers, such as local standout Ernie Fields, a pianist, trombonist and band leader.

Honky-tonk angels

All these years later, the room still holds 1,800, but it has no permanent seating. A yellow-and-red neon star glows above the dance floor, and a mirror ball dangles below.

A metal ceiling joist hangs just 9 feet above the stage, proof that the place was not built with live performances in mind. Higher above the stage hangs a banner proclaiming “HOME OF BOB WILLS.”

Oversized sepia portraits of long-ago country stars gaze down like honky-tonk angels. Kay Starr hovers over the bar. Hank Williams lingers nearby.

“Good, evenin’, Cain’s. Been a while,” drawled Marty Stuart, opening his show April 24. Behind him, the Fabulous Superlatives played tunes marrying country, rockabilly and sometimes a little surf guitar.

Spend 49 seconds in Tulsa and be startled »

Stuart, a 59-year-old singer-songwriter and sideman for Lester Flatt in the 1970s, looked as though he was born to play the room: big hair, wry wit, snappy suit, quick fingers on the fretboard.

Although the house wasn’t full, it was lively. I was near the front when bass player Chris Scruggs, grandson of the bluegrass banjo pioneer Earl Scruggs, took over an old steel guitar that had belonged to Bob Wills’ sideman Leon McAuliffe.

I was even closer when Stuart launched a solo mandolin rendition of “Orange Blossom Special,” a beloved instrumental from the ’30s that made me think of the early years of Cain’s.

Music history

In the first 20 years of the 20th century, the Oklahoma oil boom created thousands of jobs, made many families rich and pushed Tulsa’s population from about 1,400 to more than 70,000. Then came the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

White and black mobs gathered with weapons after rumors (never substantiated) spread about a black teenage boy assaulting a white girl.

Shots were fired. A few blocks east of Main Street, white Tulsans set about looting and burning Greenwood, the city’s biggest African American neighborhood, while most of Greenwood’s residents were taken into custody and held under armed guard.

In 18 hours, dozens died. Hundreds were hurt. Thousands lost homes. No arson or murder arrests were made.

Some historians say W. Tate Brady stood watch while the burning and looting continued. Many agree that Brady belonged to the Ku Klux Klan and joined in civic maneuvering to push black families away from downtown.

Sites and sounds: Visit iconic music venues throughout the country »

The more historians study Brady, the more squeamish Tulsa becomes about his name. In 2013, the City Council voted to rename downtown’s Brady Street for Civil War photographer Mathew Brady, who died in 1896 and had nothing to do with Tulsa.

In late 2017, the Brady Arts District — the booming bohemian neighborhood that includes Cain’s — was renamed the Tulsa Arts District.

To learn more, walk four blocks east from Cain’s to John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park (290 N. Elgin Ave.) and start reading plaques. The Greenwood District, anchored by two university campuses and a modest commercial block, still has many empty lots.

The bands play on at Cain’s. If the 1920s and ’30s are Chapter 1 of its story, Chapter 2 occurs in the 1940s and ’50s, when banjo and fiddle player Johnnie Lee Wills (Bob’s brother) led his house band here and crowds were notorious for their rowdiness.

New chapters, new acts

Chapter 3 is the hall’s decline in the ’60s and early ’70s. Chapter 4 is the arrival of Shaeffer, who, between mud-wrestling matches and circus sideshows, brought in up-and-coming acts such as the Police, Pat Benatar, Van Halen, U2, the Pretenders and the Sex Pistols.

Cain’s was one of just seven stops on the Sex Pistols’ first and last U.S. tour in 1978, probably chosen because their manager was looking to stir up controversy in conservative communities.

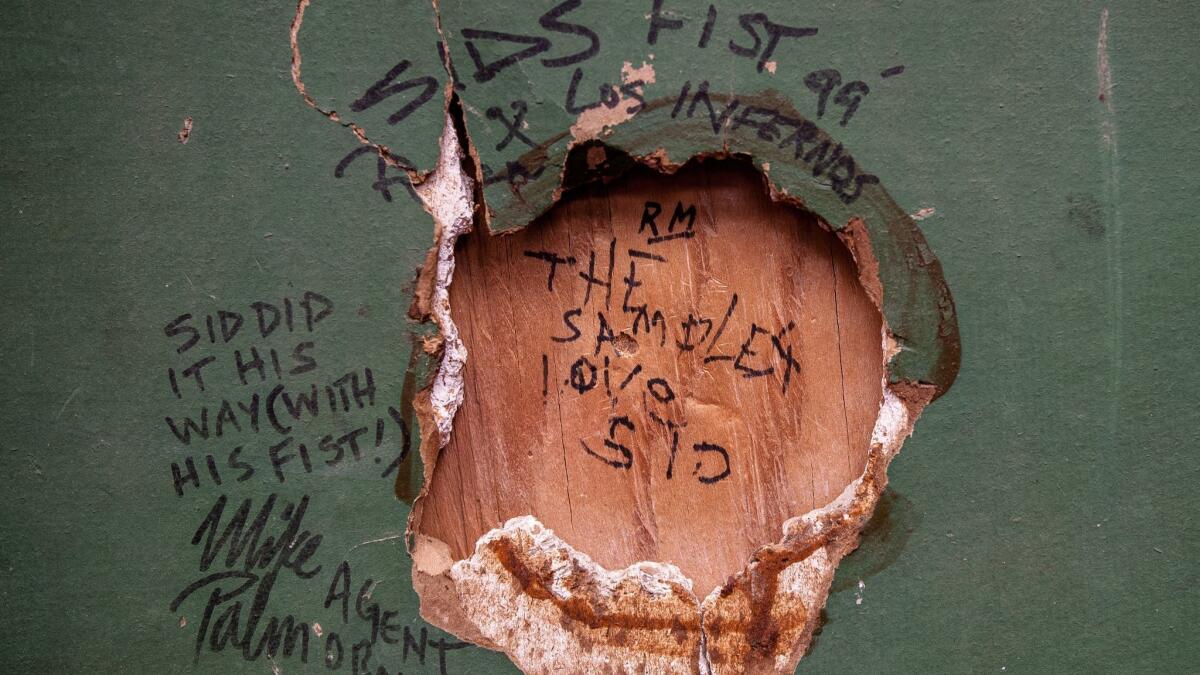

He got some. Christian protesters gathered outside, although it was a snowy January night. And Vicious, a heroin addict who would die the next year, apparently put his fist through a dressing room wall.

The current owners cut out the damaged bit of drywall, framed it and moved it to their office. The drywall, autographed by various musicians who came later, hangs above a red couch where Hank Williams passed out for hours one night in 1952.

More shows, less drama

These days, there are more shows and less backstage drama.

Brothers Chad and Hunter Rodgers, who bought the building with their parents in 2002, have installed air conditioning; lifted the drop ceiling; added a mezzanine at the rear of the dance floor; and outfitted a vast green room with couches, a big-screen TV, a pool table and a Ping Pong table. A dining room serves barbecue dinners.

They booked 132 shows in 2017, including country, rock, folk and rap. Jack White has appeared at least four times. Bob Dylan kicked off a tour here in 2004, as did Robert Plant in 2005. Kansas City-based rapper Tech N9ne and Tulsa-born singer-songwriter St. Vincent have played the hall, too.

Industry surveys regularly rank Cain’s among the world’s 25 busiest venues for its size.

Still, at the beginning, Chad Rodgers told me, “I didn’t realize what the building meant.”

On my last night in Tulsa, Cain’s was offering MisterWives, a New York-based indie-pop band that was kicking off a 14-city tour to promote its second album.

No cowboy hats, no punk posturing — just the relentless energy of six musicians, especially Mandy Lee, MisterWives’ 25-year-old singer, who sings about independence, positivity and the trials of modern youth.

In her hands, even “This Little Light of Mine” became a ferocious anthem that the roaring crowd embraced.

“I’m gonna remember this night for the rest of my life!” Lee hollered at one point.

Then, she grabbed a front-row fan’s cellphone and took it on a tour of the stage, mugging for the camera as she went, before handing it back amid more roaring.

In a hall so full of 20th century memories, this was a 21st century move. But if Bob Wills had had the chance, maybe he would have done the same.

Other arts around town

The Tulsa Arts District is bookended by the BOK Center, a gleaming arena for music and sports that opened in 2008, and ONEOK Field, a ballpark that opened in 2010.

At 102 E. Brady St., behind a door that says “No weapons allowed except guitars,” you’ll find the Woody Guthrie Center, one of many neighborhood projects bankrolled by the Tulsa-based George Kaiser Family Foundation. In April the center unveiled a new exhibit that features a virtual-reality dust storm.

Most of its other exhibits have to do with music, featuring instruments, notes and artifacts from Guthrie (1912-1967), who was born in Okemah, 64 miles south of Tulsa. (He never played Cain’s, but his son Arlo has.)

On Guthrie Green at 111 E. Brady St., locals gather for fitness classes. Vinyl thrives at Spinster Records (11 E. Brady St), and art-lovers head for the downtown branch of the Philbrook Museum at 116 E. Brady St. The big brick Brady Theater, built in 1914, stands at 105 W. Brady St.

The Prairie Brewpub pours fancy beer at 223 N. Main St. The Tavern at 201 N. Main St. serves modern pub fare. The bars Soundpony (409 N. Main St.), Yeti (417 N. Main St.) and Inner Circle (410 N. Main St.) share the same block as Cain’s.

The Oklahoma Museum of Popular Culture is due to rise on that same block by the end of 2020. A Bob Dylan Center is also expected to open in coming years, featuring a 6,000-item archive now open only to scholars at the University of Tulsa’s Helmerich Center for American Research.

If you go

THE BEST WAY TO TULSA, OKLA.

From LAX, American, Delta, Southwest and United offer connecting service (change of planes) to Tulsa. Restricted round-trip airfare from $365, including taxes and fees.

WHERE TO SLEEP

Fairfield Inn & Suites Tulsa Downtown, 111 N. Main St., Tulsa; (918) 879-1800. Standard summer rates for doubles from $114.

Mayo Hotel, 115 W. 5th St., Tulsa; (918) 582-6296. Downtown gem from 1925, renovated in 2009. Great batch of historical documents and photos in second-floor museum room. Standard summer rates rooms for a double from $121.

WHERE TO EAT

Chimera, 212 N. Main St., Tulsa; (918) 779-4303. Great for breakfast or light dinner; nothing more than $13.

Burn Co. Barbecue, 1738 S. Boston Ave., Tulsa; (918) 574-2777. Tasty brisket, pulled pork, sausage, etc. Often a line. Family-style indoor picnic tables. Open 10:30 a.m.-2:30 p.m.; closed Mondays. Lunch $9-$20.

The Bull in the Alley (also know as the Lounge), 11 E. Mathew Brady St., Tulsa; (918) 949-9803. No sign outside, just unmarked green doors beneath a small dangling bull. Dinner only. Dark room with groovy starburst chandeliers. Main dishes $25-$62.

TO LEARN MORE

Cain’s Ballroom, 423 N. Main St., Tulsa; (918) 584-2306

Tulsa Arts District. First Friday art crawls each month.

Tulsa Convention & Visitors Bureau

christopher.reynolds@latimes.com

twitter: @mrcsreynolds

Instagram: mrcsreynolds

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.