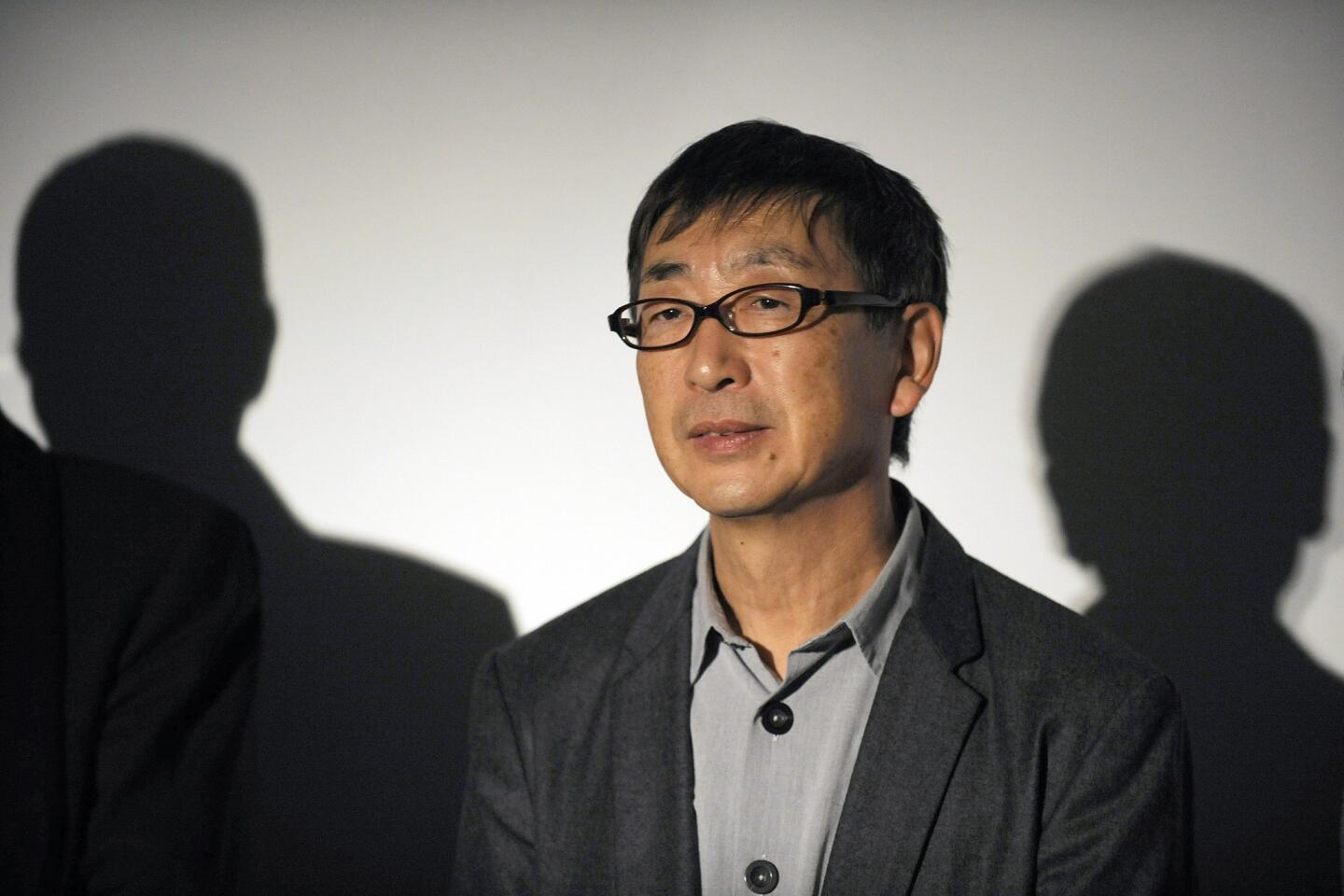

Toyo Ito’s architecture beckons a critic to Asia

Jet lag can do strange things to a person. But it wasn’t just a mixed-up body clock that had me awake at 3 a.m. during a trip to Japan a few years ago, madly scrolling through online ferry schedules and trying to plot a route by train, boat and taxi to a new architecture museum on the southern island of Omishima. It was also a long-standing interest — OK, maybe an infatuation — with the work of Japanese architect Toyo Ito.

Since the economic crisis of 2008, there’s been a substantial backlash against the idea that critics should write exclusively, or even mostly, about stand-alone buildings by prominent architects. We’ve found broader and more complex ways to explore the relationship between architecture and society. The culture of “starchitecture,” that overused if sometimes bluntly effective term, has lost its luster.

But we make an exception for Ito, who won the Pritzker Prize, the field’s top honor, in 2013. One of the deans (with Arata Isozaki and Tadao Ando) of Japanese architecture, he is, at 73, one of the few designers who can make a critic drop everything to get on a plane to see one solitary building in some remote part of the world.

In large part, his work appeals to even the most jaded observers of contemporary architecture because of its rich variety. Unlike Zaha Hadid, Norman Foster or Daniel Libeskind, whose buildings are stamped with a recognizable signature, there’s an elusiveness to Ito’s output. He’s designed small houses, aerodynamic glass towers and low-slung, geometrically complex museum buildings. A recent essay by architecture critic Thomas Daniell — with apologies, presumably, to Harrison Ford — calls Ito “The Fugitive.”

Ito has also incorporated technology and new construction techniques into his work without making a fetish of them, a skill that seems to keep his buildings from looking mannered or dated. An Ito project from the 1980s can seem as fresh and worthy of exploration as one that has just opened.

But more than anything, what makes an Ito building stand out is something quite basic: In an era when many architects such as Eero Saarinen, are acclaimed for impressive rhetoric or jaw-dropping computer renderings — or both — he has earned his following in purely architectural terms. He knows how to build, to shape space in a way that respects traditional craftsmanship and seems utterly contemporary.

I’ve seen buildings by Ito in Tokyo and other Japanese cities, but there are a number of important ones I’ve yet to visit. Because Ito has never built in this country — his elegant proposal for a new Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive was derailed by the 2008 downturn — my ideal Ito tour would be limited to Asia, stopping at each of his key projects.

I wish the first stop could have been the famed U-House that Ito designed in 1976 for his sister, recently widowed, and her two daughters in Tokyo.

The house was demolished in 1997, but it remains central to Ito’s career. At a time when other architects were just starting to experiment with the references to historic architecture that would come to be called postmodernism, a young Ito designed a house that was abstract and somber, even monolithic, with the legs of the U wrapping around a courtyard and the roof sloping down to lower interior walls.

The razing of the house only added to its legend, in part because Ito, having designed it in part as a place for his sister to mourn her husband’s death, didn’t protest the demolition. She left the house when she was ready to move on with her life.

Though the house is no longer there, architectural experimentation is very much alive in Tokyo, making it among the most attractive destinations in the world for anyone interested in contemporary design. As is true in Los Angeles, a healthy proportion of the city’s most innovative buildings are tucked away in the private realm. Houses by the Tokyo-based architects Sou Fujimoto and Go Hasegawa and the duo Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, heirs to the U-House in their layered, sophisticated minimalism, are worth seeking even if you can see them only from the outside.

Ito has also joined a number of leading contemporary architects in designing Tokyo boutiques for high-end fashion brands along or near Omotesando, a wide tree-lined avenue in the upscale Shibuya section of the city. From Ito’s store for Tod’s, a skinny glass box wrapped in a white skin that resembles a screen of tree branches, it’s a short walk to a Prada store by the Swiss architect firm Herzog & de Meuron, an Hermès branch by Renzo Piano and a Coach flagship by Rem Koolhaas and his firm, Office for Metropolitan Architecture.

After Tokyo, the next stop on an Ito tour would be the Mediatheque building, which opened in 2001 in Sendai, a pleasant midsized coastal city in northeast Japan, and instantly raised the architect’s international profile. The seven-story building holds a library, gallery space and community rooms — a complicated collection of spaces that Ito unifies through ingenious structural means. His design wraps the building’s mechanical equipment inside 13 vertical tubes, which also make up the structure of the tower, leaving the rest of each floor free of columns.

The building’s innovative structural approach was vindicated when it survived the powerful 2011 Japan earthquake with virtually no damage. When I toured the building about 10 months after the quake, it appeared unscathed. Mediatheque also stands out in Sendai because of its thoroughly unremarkable surroundings. It rises on an extensively landscaped boulevard lined on either side by nondescript if upscale shops, restaurants and apartment buildings. Imagine an innovative Frank Gehry tower on one of the nicer stretches of San Vicente Boulevard.

Praise for Sendai Mediatheque from critics and architects around the world helped Ito land a number of commissions outside Japan. Our next stop, as a result, would be 1,500 miles from Sendai in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, where Ito’s World Games Stadium opened in 2009. Stadium design in the United States is an architectural backwater, with firms churning out either bland nostalgia palaces wrapped in red brick (for baseball) or sleek, oversized stacks of luxury boxes (for football). Ito’s stadium, which uncoils like a snake across its waterfront site, its skin of nearly 9,000 solar panels glinting in the sun, suggests there’s life in this building type yet.

Also in Taiwan is the Taichung Metropolitan Opera House, a project that seems destined to define Ito’s late-career work. The hulking box of a performance space, covered with a spray-on concrete skin, has been producing more anticipatory buzz among architecture critics than any other building in the world.

Set to open next year, the opera house will offer a test case for whether Ito’s personal, patient and idiosyncratic style, which has worked so well for houses and towers with small footprints such as Mediatheque and the Tod’s store, can be stretched to fit a full city block.

I never made it to Omishima Island on that trip to Japan, but it qualifies as a perfect final stop on my ideal tour of Ito’s work. Omishima is one of a constellation of islands in the Seto Inland Sea, about 300 miles southwest of Tokyo, dotted with museums and other cultural facilities. It was there in 2011 that Ito designed a museum to show, catalog and celebrate his own career. The Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture occupies a pair of buildings: a silver steel hut (a re-creation of Ito’s own 1984 house in Tokyo) and a dark-brown steel hut.

As architects’ monuments to themselves go, this one is modest. It’s also driven by an interest in stripped-down yet muscular geometry that appears almost nowhere else in Ito’s work. The brown steel hut is a pile of hard-edged forms, pyramids on top of rhomboids; the silver hut is covered by a seemingly mismatched collection of vaults.

In part, this approach flows from a reaction to the landscape. The view is of the wide ocean and undulating coastline and is frequently obscured by clouds and rain. To produce something gracefully curvilinear here would have been to ape nature in a manner that Japanese architects tend to distrust as too much on the nose. Instead Ito tried to give the site precisely what it didn’t have — not just to avoid repeating the lines that were already there but also to carve out a powerful space for architecture to do its own work.

Maybe in the end that’s why we architecture obsessives will happily travel so far, or imagine doing so, to see a lone building or two. That odd and productive co-dependence of design and place, architect and site, is a relationship that doesn’t really exist in any other art form.

Sculptors who work on a large or public scale do something similar, and I suppose photographers and certain filmmakers try to knit their work into a particular setting.

But in the end it’s only architecture that does so directly, without detachment or mediation.

As a result, there’s a reward in reaching a landmark that’s palpable — and can provide a jolt of energy. I often run myself ragged trying to find an obscure building by a talented architect. But once I’ve found the place and started looking and walking around, that sense of exhaustion disappears right away nearly every time.

This story is part of the Los Angeles Times’ Image Magazine spring fashion and travel issue.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.