In Darfur, another obstacle to peace

TULUS, Sudan — Three years after it was burned to the ground, the village of Tulus in Darfur is springing back to life.

Corn and sesame sprout from fertile fields. Children play around newly built huts. Smoke from cooking fires once again rises from the land.

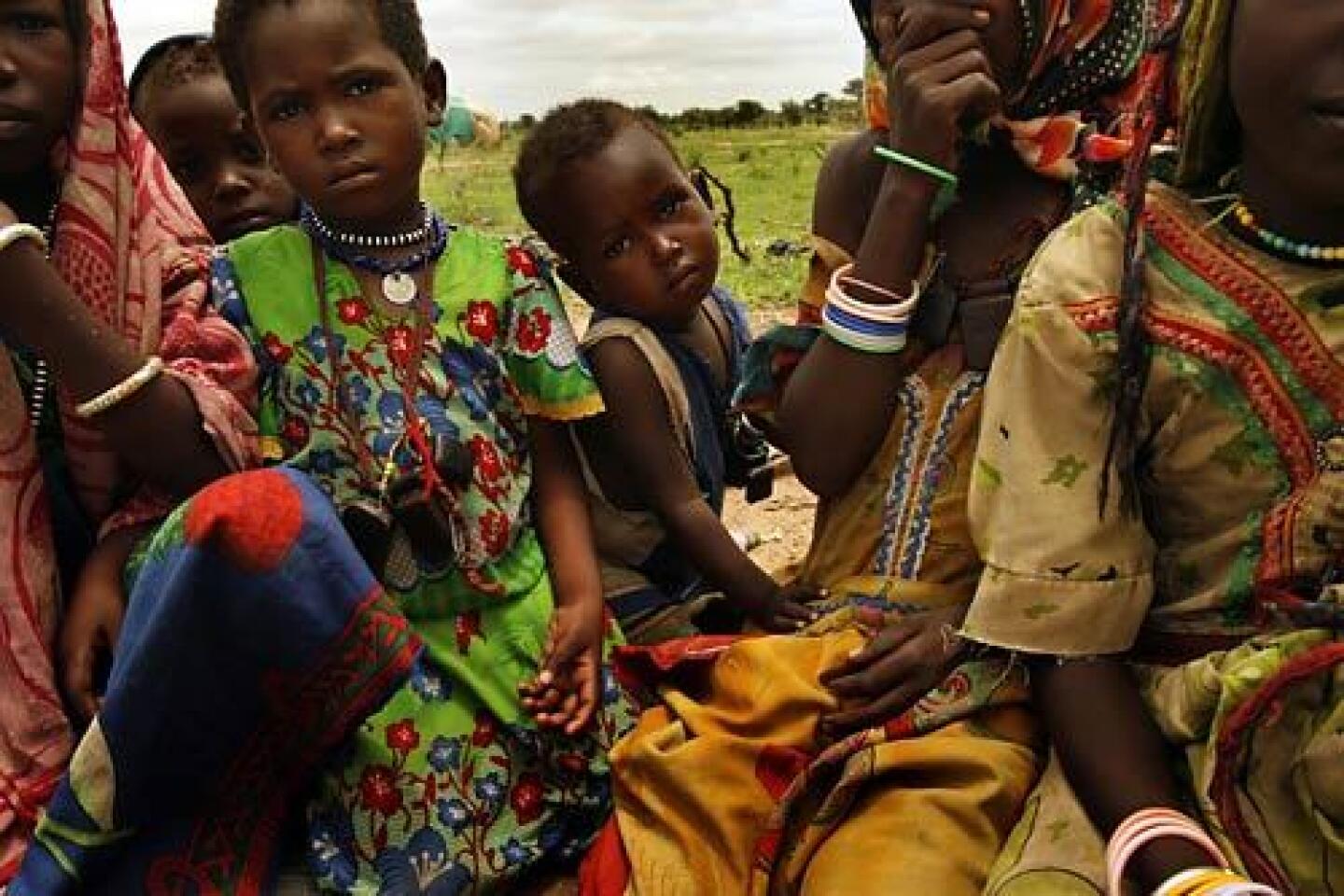

Problem is, those rebuilding Tulus are not the original inhabitants, who were chased away by pro-government Sudanese militias in 2004 and are afraid to return. Instead, their place has been taken by Chadian Arabs, who recently crossed the border to flee violence in their own country.

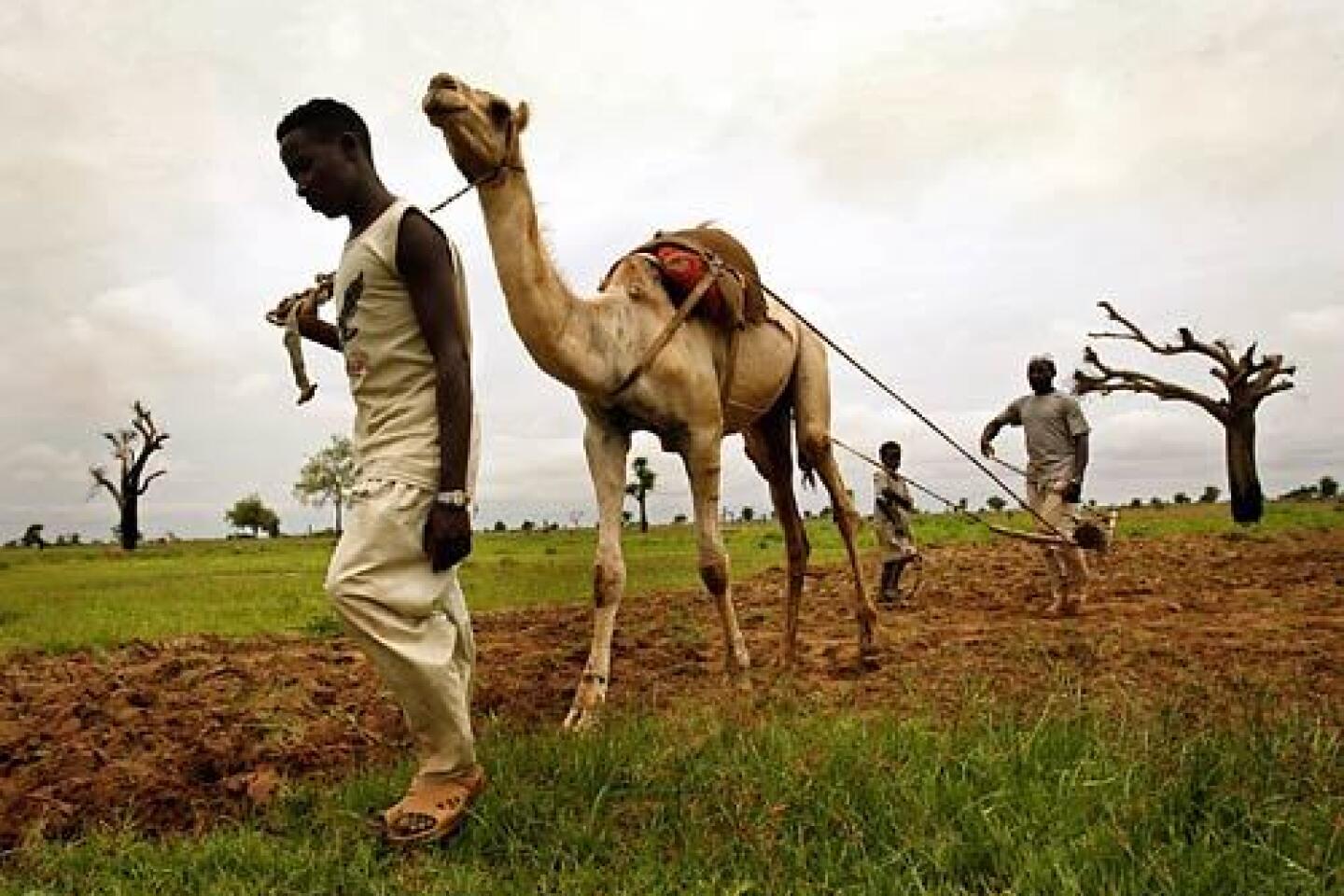

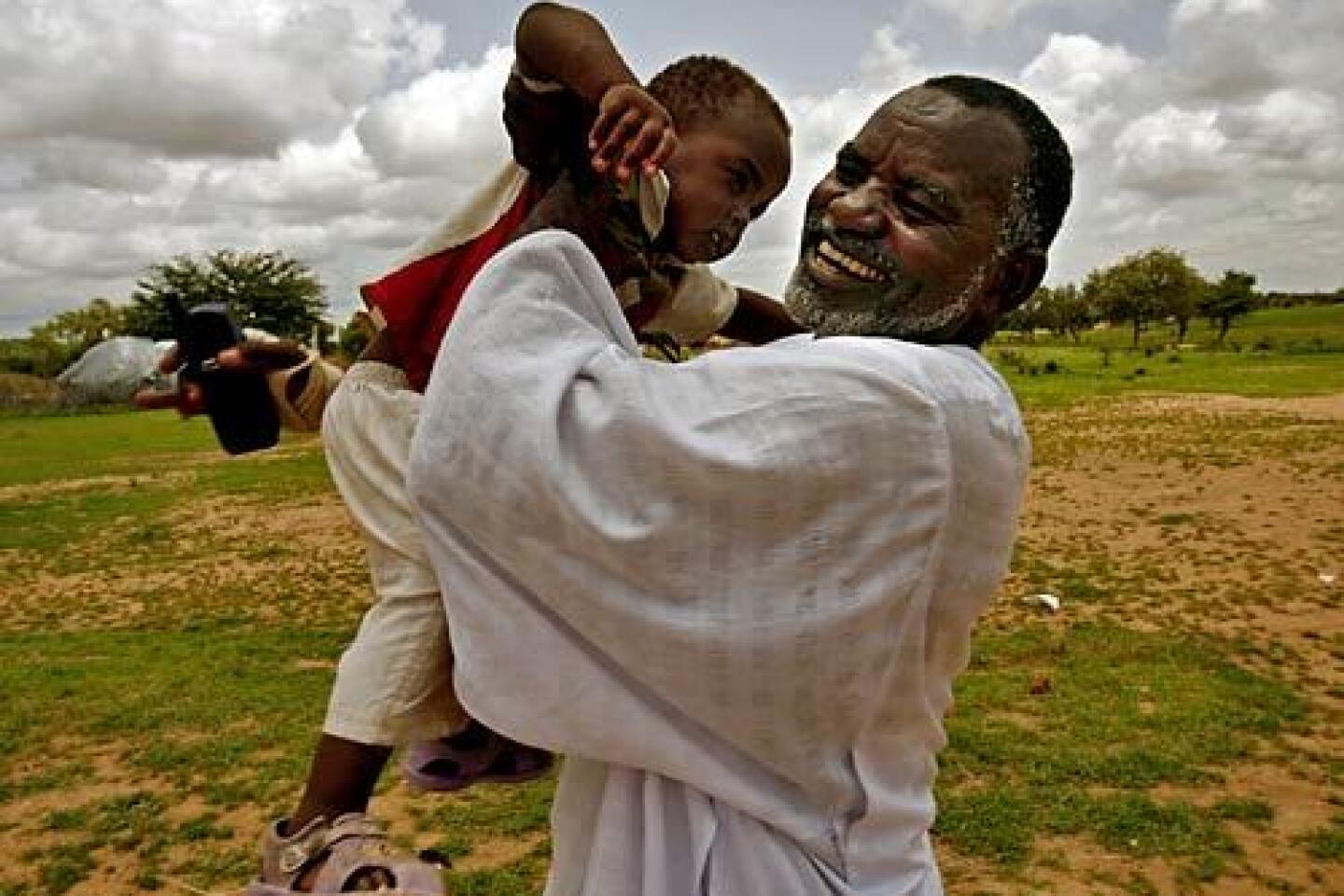

“It’s comfortable here,” said Sheik Algooni Mohammed Zeean, 42, leader of 150 Chadian Arabs who in March settled on a grassy plain not far from the ruins of Tulus’ abandoned homes and school. Gesturing toward the fields bearing their first harvest in Sudan, he smiled. “I feel like this is my home now.”

Over the last six months, nearly 30,000 Chadian Arabs have crossed into Sudan, many of them settling on land owned by Darfur’s pastoral tribes that have been driven into displacement camps, aid groups say.

This migration has quickly become the latest obstacle to peace in western Sudan, drawing the attention of international observers and protests from those displaced from Darfur, who accuse the Sudanese government of orchestrating an “Arabization” scheme by repopulating their burned-out villages with foreigners.

“This is a government plot to give our land to Chadian Arabs,” said Mohammed Abakar Mohammed Adam, 27, a farmer from the village of Bechabecha, which he said was abandoned after armed nomadic tribes known asjanjaweed, widely believed to be backed by the government, attacked in 2003. But in recent months, Chadian newcomers have begun building homes atop the remains.

The Darfur conflict began in early 2003 when rebels attacked government forces to protest the poor resources and services in the neglected area. The regime in Khartoum, dominated by Sudanese Arabs, is accused of stirring up ethnic hatred by arming militias to attack villages that supported the rebels, many of whom increasingly call themselves “Africans.” U.S. officials have labeled the government’s campaign genocide. An estimated 200,000 people have died, mostly from disease and hunger in the early days of the crisis.

The recent influx of Chadian Arabs reflects the conflict’s spread over the border, where similar clashes based on ethnic differences are destabilizing eastern Chad. Over the last year, nearly 50,000 Chadian refugees have sought shelter in Darfur, though most of the earlier arrivals were not Arab and settled in refugee camps.

Government officials in Khartoum have said little publicly about the recent influx.Sudanese Arab leaders in West Darfur are welcoming the Chadian Arabs, directing themto the vacated land and assisting them with food and supplies. They insist they are simply helping their Arab brethren at a time of crisis and that the newcomers will return to Chad as soon as it’s safe.

But for some displaced Tulus villagers, now living less than 20 miles away in Habillah, news that strangers are cultivating their land has brought suspicion and anguish.

“That is our land,” said Miriam Yahya Ahmed, a 60-year-old widow with four adult children. “Those people should go.”

In Tulus, she lived on a small farm with fields of corn and peanuts. Now, the hunched, gray-haired woman struggles to nurture a few dozen corn stalks on a dirt patch behind her straw hut. International humanitarian groups worry that disputes over the land might reignite violence in western Darfur and lead to further delays in resolving the region’s massive displacement crisis, with more than 2 million people driven from their homes.

“The mere presence of people on this land will make it more difficult for [displaced persons] to return home,” said Ita Schuette, head of the Habillah branch of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the world body’s refugee agency, which has been monitoring the influx.

Tensions have been heightened by rumors that some Chadians have been offered Sudanese identification cards or papers to help them establish citizenship. One Darfur hospital was reportedly asked to forge 100 birth certificates, according to a U.N. official. In another reported case, Chadians were allegedly photographed for ID cards in the city of Foro Burunga.

U.N. officials have been unable to confirm those reports and said they have found no ID cards or evidence that the government was plotting to get Chadians to immigrate. After interviewing hundreds of Chadians, the agency has concluded that many are entitled to refugee status because of the violence in their home country.

But leaders with the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, the former rebel army in the south, lodged a complaint in parliament in May about the Chadian migration. SPLM officials, who reached a power-sharing agreement with Khartoum in 2005, fear that Chadians will be issued fraudulent voting cards in an effort to sway the upcoming national census or next year’s presidential election.

Others worry that the presence of Chadian Arabs will draw attacks by Darfur rebels and further destabilize the region.

West Darfur’s Gov. Abu Gasim Imam, a former rebel commander whose group signed last year’s controversial peace deal with the government, said he plans to dispatch about 1,000 troops to keep the peace. He expressed solidarity with displaced Darfur residents and said the Chadians should be relocated to refugee camps.

“We are very engaged in protecting the land for the original owners,” Imam said. He said some Chadians might be legitimate refugees, but suggested others had ulterior motives and might be working in conjunction with Sudanese Arabs.

“This is not simply a refugee crisis,” he said. “It’s a strategic attempt to occupy land.”

U.N. officials are pressing leaders in Khartoum to publicly reaffirm the property rights of the displaced. Under the 2006 Darfur peace agreement, the government granted the right of return to those displaced by violence, but an existing Sudanese law states that owners lose their rights if they abandon land for more than a year.

The U.N. also wants the government to designate the Chadians as refugees, which would allow them to be relocated to camps. Such a move might also alleviate citizenship concerns, since it would be difficult for people registered as Chadian refugees to later claim they are Sudanese.

The majority of Chadian Arabs have rejected offers of humanitarian aid and efforts to relocate them to camps, saying they brought most of their belongings with them, including food, seeds, tents and herds.

“For those who need help, we are giving out of our own pockets,” said Al Hadi Ahmed Shineibat, a Sudanese Arab sheik who has been assisting Chadian arrivals asthey cross the border. Shineibat is the brother of Abdullah abu Shineibat, an alleged janjaweed leader cited by the State Department for attacks against Darfur villages in 2003 and 2004. Last year, Human Rights Watch accused Abdullah abu Shineibatof launching attacks in eastern Chad.

Ahmed Shineibat and other Sudanese Arab sheiks appear to be taking the lead role in assigning Chadian arrivals to disputed land in Darfur. In some cases, they have sent trucks to transport newly arrived Chadians to their assigned land. Some are also charging rent, even though they do not own the land.

So far, the influx of Chadians has avoided problems usually associated with sudden, conflict-driven displacements, such as food shortages or overcrowding. “It appears to be very well organized,” Schuette, the U.N. official, said.

Resting under a tree in his home village of Um Samgamti, Ahmed Shineibat dismissed claims that the Chadian migration was part of a government-organized land grab. He predicted most Chadians would return as soon as it was safe.

“We told them when they first arrived that when the owners of the land return, they will have to leave,” Shineibat said. “The land is not being occupied. It’s just being used temporarily by guests. They are not Sudanese. So eventually they will have to leave.”

He said Chad and Sudan have a long history of cross-border migrations and land sharing, particularly during periods of strife, and that land is traditionally returned to the original owners.

Despite his assurances, some Chadian Arabs appear to be digging in their heels. A group of about 300 who arrived in Tulus before the most recent wave initially identified themselves to U.N. interviewers as Chadian. Earlier this month, their sheik changed his story, claiming the group was from Darfur.

“We’re Sudanese,” said Sheik Ismail Mohammed Shein, 57. “This is our land. We are not leaving.”

He claimed to have a government ID card to prove his assertion, but declined to show it.

A few miles away, those who arrived more recently with Zeean take a more conciliatory approach. They say they were chased from their village by Chadian soldiers and walked seven days with only what they could carry on their backs.

At first, the group’s leader feigned ignorance about the original inhabitants of Tulus, saying he assumed the land was abandoned. Later Zeean acknowledged he was aware of the controversy over their arrival and the fears of the former residents. He vowed to leave the land if the owners returned.

“Our land in Chad is better anyway,” he said.

Asked what he would do if he returned home to find strangers occupying his property, Zeean didn’t hesitate: “I’d tell them to leave,” he said. “That’s my land.”

edmund.sanders@latimes.com

Times staff writer Maggie Farley, who was recently in Darfur, contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.