Fishermen in Goa, India, dread return of mining

In 2012, when the Supreme Court of India banned iron ore mining in the coastal state of Goa, fisherman Suresh Parab breathed a sigh of relief.

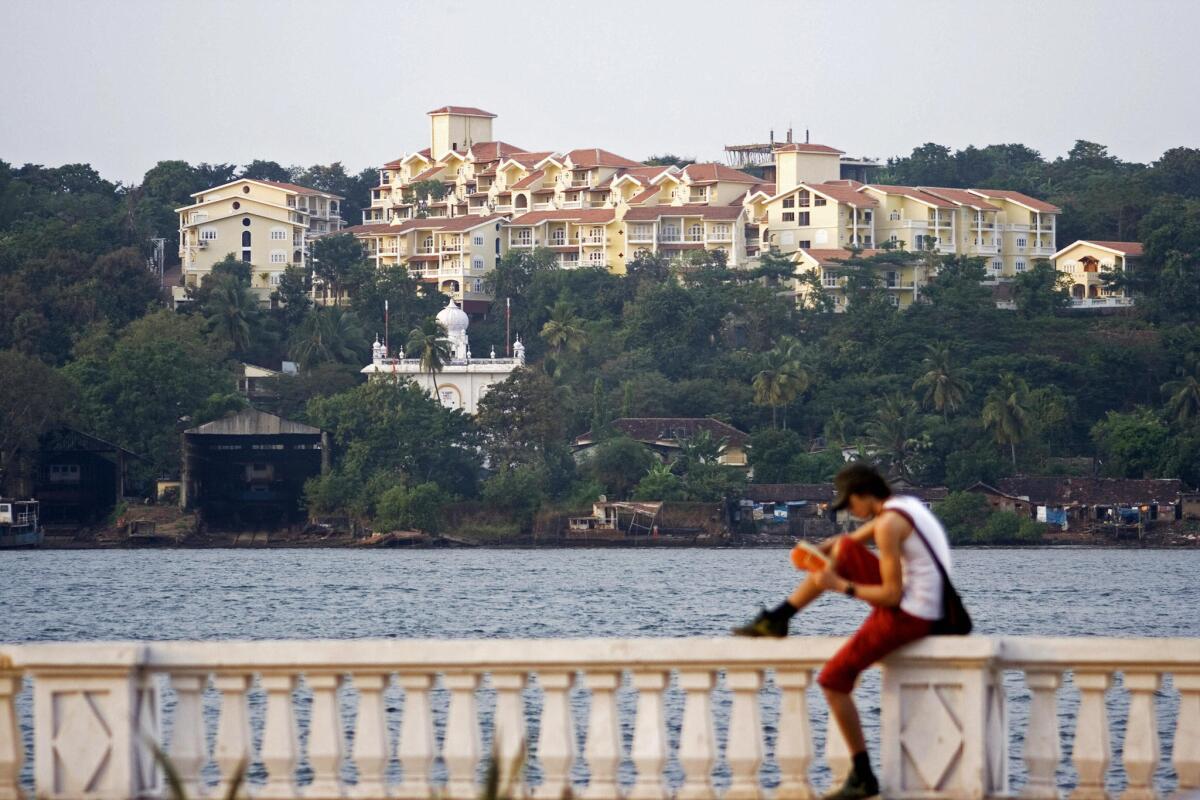

More than 20 large mines had been operating in Parab’s favorite fishing spot: the catchment area of the Mandovi River, Goa’s largest. Cargo ships traveling to and from the mines dripped oil and other contaminants into the river, he said, making “our lives miserable.”

“Time and again, the water pollution made the river turn red,” said Parab, 61, sitting in the veranda of his palm-fringed house in the northern Goa village of Amona. A tiny lane adjoining his house leads to the Mandovi, known as Goa’s lifeline.

“It was exceedingly difficult to find quality fish,” he said. “The customers knew it and negotiated a lot. Often we sold it at a throwaway price.”

The fishermen are now facing a return of the mines. In April, the Supreme Court lifted the ban and said mining could resume in Goa once companies obtained fresh leases. That could occur as soon as March.

The 2012 ban came after a government-backed inquiry found that 90 mines were operating without mandatory environmental clearances, costing Goa billions of dollars in revenue as companies rushed to feed China’s demand for iron. Activists say authorities even allowed mining in forest areas where wildlife was present.

Industry groups say as many as 1 million jobs were lost because of the ban, and have been seeking to overturn it. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government also is exploring plans to cut export duties on iron ore to help revive Goa’s mining sector, which produces metals mainly for export.

Fishermen and advocacy groups worry that water sources will again be severely contaminated and farms devastated by silt from the mines. They allege that waste from the mines, which contained graphite, collected on riverbanks and washed into the water during monsoon rains.

Environmental activist Ramesh Gawas said unlicensed mines caused irreversible damage to biodiversity, water aquifers, fisheries, agriculture and forests.

Mines that ran nearly the entire 65-mile length of Goa’s coastline generated more than 100,000 tons of mining waste per year, according to the Center for Science and Environment, a nonprofit research group in New Delhi. India’s National Institute of Oceanography found that 70,000 tons of iron particulates were deposited in the Mandovi annually because of the mining.

“For us, mining means trouble,” said Parab, fidgeting with his fishnet.

The Goa Foundation, an environmental action group, said that one of the 90 mining companies found to be doing business illegally, SESA Goa, made more than $821 million from 2003 to 2010. The government, meanwhile, took in $47 million from mining activities during the same period, the group said.

“Iron ore is a property of the government and Goans, not mine owners,” said Claude Alvares, executive director of the foundation, which filed the successful lawsuit against illegal mining in the Supreme Court.

But Vishram Gupte, a prominent writer in Goa, said the mining created jobs and improved the state’s economy, which also relies heavily on beach tourism.

“Getting completely rid of mining would be devastating for Goa’s economy,” Gupte said. “But it must happen within legal limits, not the way it transpired earlier. Mine owners made nonsensical profits.”

Many fishermen have left the trade since the stock in the Mandovi, which also included clams, shellfish and oysters, all but disappeared. The state forest and environment ministry in June ordered a probe into the die-off of clams at Velim, a coastal village in southern Goa.

Alvares said shellfish used to be a regular part of his diet. “But I do not remember the last time I had one,” he said.

Opponents of mining believe the government has been under pressure from companies to keep environmental impact information from becoming public. Activist Gawas labeled mine owners “the super-gods of Goa.”

In August, Madhav Gadgil, a respected ecologist commissioned by the state to study the effects of iron mining, said he had submitted his findings to state officials but they had not released them.

Officials say that new safeguards, including a transparent auction process and a blacklist of companies that mined illegally, will prevent past abuses from recurring.

“Mine owners who plundered natural resources and did business unethically will not be considered,” said Parag Nagarsekar, deputy director of Goa’s department of mining and geology. “Mistakes that happened earlier will not be repeated.”

Gupte and others said mining should return only on a limited scale. Areas where mining was undertaken are starting to become lush and green again, and air quality has improved noticeably, he said.

“It is important to strike a balance between environment and employment,” Gupte said. “If mining is done within legal constraints, it is possible to generate revenue without destroying our environment. But the question is: Do mine owners and the government have that honesty?”

Parth M.N. is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.