For 800 years, they were celebrated as martyrs to their faith. Just one problem: The Cathars may never have existed

They lived simple lives of austerity and abstinence and suffered horrifying deaths, cut down by marauding armies and burned at the stake as heretics — or so the legend goes.

For their considerable pains, the Cathars were memorialized and celebrated as martyred religious rebels by a region of southern France that, eight centuries later, still promotes itself under their name: Pays Cathare.

But in recent weeks, a debate has erupted across this region in newspapers, tourism offices, and in research conferences following an academic exhibition that explored a more modern-day heresy: The Cathars never existed.

“People imagine that these people died as heroes, in defense of their faith and against corrupt powers,” said Alessia Trivellone, a history professor at Paul-Valery University in Montpellier who organized the exhibit. “They feel that the very idea of going back to investigate this painful story is unbearable.”

Trivellone is one of a growing number of early modern Europe scholars who have cast doubt on the Cathars’ existence, and her role as organizer of the exhibit has made her the target of critics who call her a “negationist.” Along with other maverick historians, she is dismissed as an upstart just trying to generate buzz and further her career.

Yet the intensity of the backlash reveals something deeper: the lingering regional resentments over Paris’ domination of the country’s culture and economy.

The 13th century slaughter of the Cathars is associated with the region’s loss of autonomy to the kingdom of France, which proceeded to systematically wipe out the language and culture of the south in favor of northern values.

Such wounds remain fresh in a highly rural region that struggles economically, where people believe the north’s elite view them as unrefined hillbillies with odd accents. The anger bubbled to the surface in recent weeks with the “yellow vest” protests against President Emmanuel Macron.

“To people here, the crusade against the Cathars looks rather like a colonial war,” said Monique Boulze, who is in charge of promotion at the tourist office in Beziers, which was burned to the ground in one of the crusade’s most infamous episodes. “It’s something still present and alive in local history.”

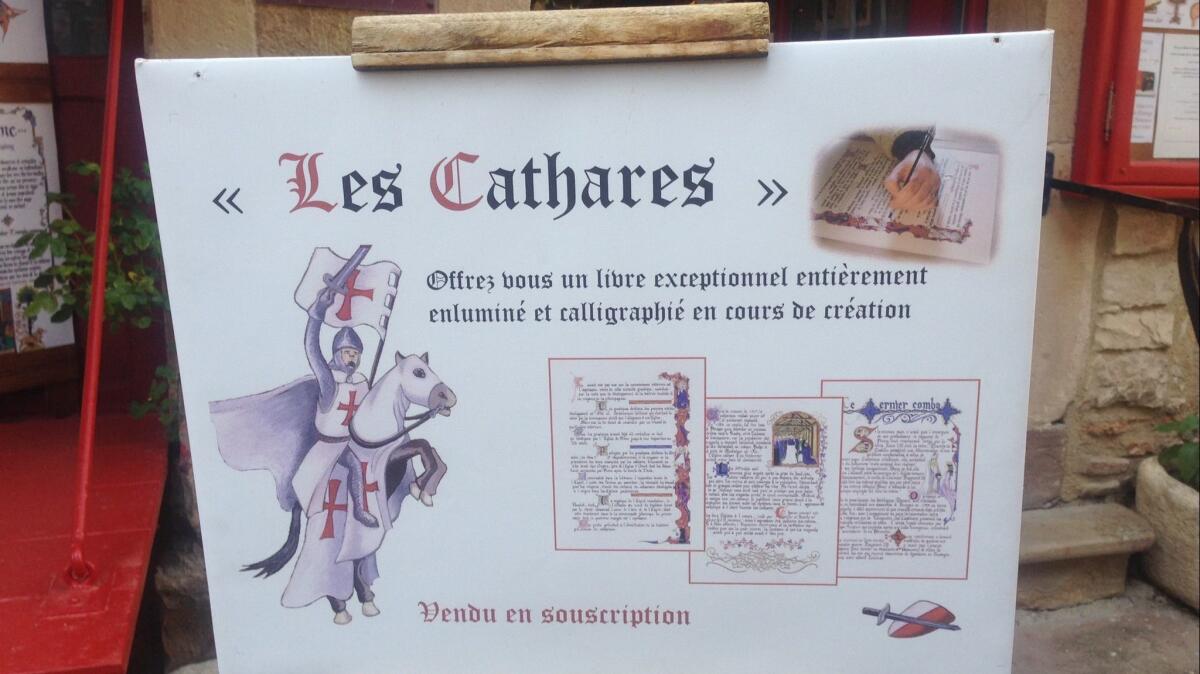

Any tourist visiting this region would find it hard to miss the ever-present signs and historical markers recounting the tragic tale of the Cathars.

The city of Albi is dominated by the massive Cathedral Basilica of St. Cecilia, a 200-year construction project launched by the Catholic Church after the Cathar crusade, supposedly to remind locals who was boss. Farther south, the town of Mazamet is home to the Cathar Museum. And in Beziers each August, the town shows a sound and light spectacular called: “The Cathars, the Treasure of Beziers.”

“What our region has retained from the tragedy of the Cathars,” says the narrator, “is the taste of rebellion. And the taste of liberty.”

At first blush, the Cathars make for unlikely modern-day heroes. They are said to have been fundamentalists who believed there were two gods: A good one who presided over the spiritual world, and an evil one who ruled the physical world. Cathars viewed even sex within marriage and reproduction as evil, and so lived strict lives of abstention.

More appealing today, however, is the idea that the Cathars mounted the first major rebellion against the Catholic Church. They saw Rome as corrupt, rejected the church’s hierarchy, and did not build cathedrals but rather worshiped outdoors. This lack of structure gave women more prominence and freedom, and because they were pacifists who repudiated all killing, they were vegetarians.

Much about the history of 12th and 13th century France may today be fuzzy. But there is no dispute that in 1209, at the urging of Pope Innocent III, a band of northern French nobles rallied an army that swept into the south, where they unleashed a crusade so bloody it would make “Game of Thrones” look tame by comparison.

This included the sacking of Beziers in July 1209 by an army under papal authority. Just before the attack, which would kill as many as 20,000 men, women and children, the pope’s man on the scene, Arnaud Amalric, is reported to have uttered one of history’s most famous orders: “Kill them all. God will know his own.”

To wrap things up after the majority of fighting was done, church leaders began a grand inquisition in Toulouse. Suspects were rounded up, forced to confess, and then sometimes burned at the stake. This became the blueprint for the much larger inquisitions carried out in the centuries to come.

In mid-October, as part of an annual nationwide science festival, Trivellone organized an exhibition called, “Les Cathares, une idee recue?” That translates literally as “The Cathars, an idea received” but implies something that is widely accepted as fact but probably not true.

The exhibition is modest, consisting of a handful of posters, a video, a comic book, and a few items that summarize the conclusions of some medieval scholars: There are no significant records from the time that support the idea that a single religious movement called the “Cathars” ever existed across southern France.

The subject, along with the exhibit’s somewhat provocative title, proved to be catnip to regional journalists, and soon local newspapers were publishing dueling interviews with scholars who were hashing out the details of ancient texts.

“Myths are the very foundation of a social group or of a civilization, a sometimes indispensable cement of societies,” Trivellone said. “The myth of the Cathars is even stronger because it allows people to identify with the vanquished of history.”

This latest wave of attention has been vexing to local Cathar scholars who have spent decades battling to have their work taken seriously. University of Toulouse history professor Pilar Jimenez-Sanchez, for instance, has been among those medieval scholars in the south who have been scouring what limited archives exist from that time to stitch together a picture of the Cathars.

It’s been a struggle, she said, because there was a feeling the broader French academy didn’t take the work seriously.

Cathar scholars say doubters are too hung up on the name. They acknowledge that at the time, such heretical groups sometimes used a variety of different names and that some rituals varied. But references to “Cathars” in letters by the pope as well as some other contemporaries, along with intensity of the crusade and the inquisition, offer ample support to prove the group as a whole existed.

Rather than being a marketing ploy, the reemergence of interest in the Cathars over the last half a century has been the fruit of that scholarship and digging, Jimenez-Sanchez said. In the wake of the Montpellier exhibition and the media attention, she organized a late October presentation in Carcassonne to rebut the idea that the Cathars were a latter-day invention.

The Cathar defenders pose a question to the skeptics: If the crusade was not about quashing this religious movement, then what motivated so many Christians to take up arms and kills thousands of other Christians?

“How do we resolve this question?” Pilar-Jimenez said. “How could people at this time have reacted in this manner?”

The Cathar debate doesn’t seem to be hurting the region — the revival of interest in its cultural history shows no sign of slowing. Two years ago, in an effort to shift some power away from Paris, the French government fused together regional governments to create far larger administrative zones.

In the south, the regions of Languedoc-Roussillon and Midi-Pyrenees were merged into France’s largest regional government by land size. In a vote to name the new region, the first choice of residents was clear: Occitanie — an homage to the language, Occitan (“langue d’oc”), a cousin of Catalan that was widely spoken in Cathar territory before the crusade.

And so, more than 800 years after the brutal crusade, Occitanie is the name of a geographic territory that is roughly the size of Austria.

“The medieval history of Occitanie is rich and fascinating,” Trivellone said. “It does not need the ghost of the Cathars to arouse interest.”

O’Brien is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.