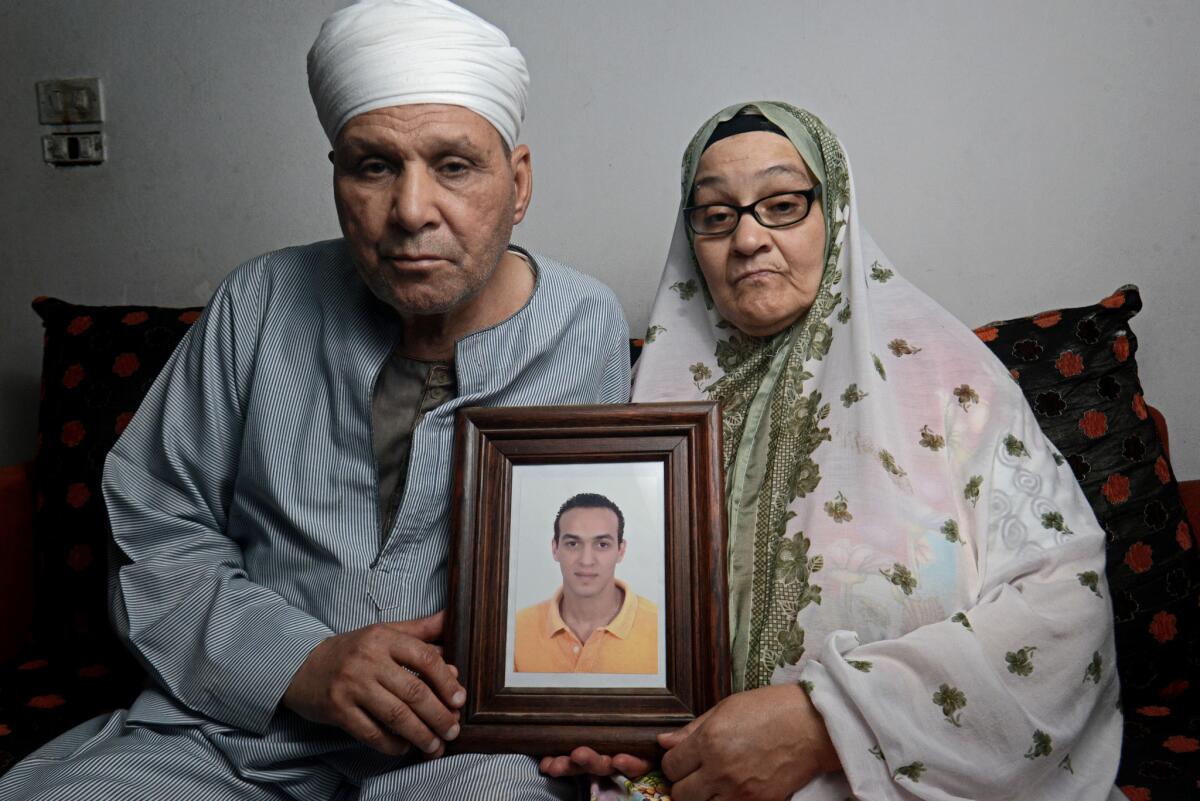

Jailed for 5 years, journalist arrested in Egypt could face death penalty. ‘We miss everything about him,’ his father says

“Who’s this?” Reda Mahrous Ali asked her grandson, pointing to the framed photo of a young man.

“Uncle,” responded 3-year-old Omar. The boy and his uncle had just met for the first time the day before.

Ali’s joy momentarily masked the grief she’s carried since her son was arrested five years ago while taking photographs of the bloody clashes between security forces and supporters of the former president. Hundreds were killed in the violence, and hundreds more were arrested.

An award-winning journalist who was on assignment for the former British photo agency Demotix when he was arrested, Mahmoud Abou Zeid is charged with a variety of criminal offenses — illegal assembly, possession of a weapon, murder, attempted murder — and could finally learn his fate this Saturday, when a verdict is expected.

Among the possible outcomes could be a death sentence if the courts find him guilty.

His family said Abou Zeid, who is widely known by the nickname Shawkan, is innocent and the charges trumped up. Reporters Without Borders, which promotes and defends freedom of the press around the world, said it considers the case against the photojournalist to be “one of the most appalling attacks imaginable on journalism.”

During his five years behind bars, Abou Zeid’s close-knit family — including his parents and two older siblings — have been his rock. They’ve structured their lives around his incarceration, visiting him, offering encouragement and trying not to let their own fears show. But it’s been a long and distressing journey for them too.

“He is scared and we are scared as well,” said Ali, a warm and jovial 62-year-old woman who cried as she described how good-natured and principled her son is, even in jail. “He told me to pray for him.”

Abou Zeid, 31, was arrested Aug. 14, 2013, while covering the violent dispersal of a sit-in held in support of former President Mohamed Morsi, who was overthrown by the military while the movement he belonged to, the Muslim Brotherhood, was banned. Human rights groups estimate at least 900 were killed that day and thousands more injured.

He was initially detained with an American and French journalist but they were released that same day. One of those journalists, Mike Giglio, wrote for BuzzFeed in 2015 that Abou Zeid was armed with nothing but a camera, and was only doing his job when he and others were swept up by authorities. Giglio said he believes he was quickly freed because he was a Westerner, while Abou Zeid was imprisoned because he was not.

“My last memory of Abou Zeid has him kneeling on the [basketball] court amid rows of other prisoners,” Giglio wrote.

Abou Zeid’s plight has garnered international attention and, to many, he has become the face of Egypt’s fierce crackdown on press freedoms under President Abdel Fattah Sisi, who was elected in 2014. Amnesty International calls the photojournalist a “prisoner of conscience” and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization honored him last spring with their press freedom award.

“We know he is innocent,” said his father, Abdel Shakour Abou Zeid, 70.

“Year after year keeps passing and we are tired, as we are old, and we have suffered over the past five years. We’re physically and mentally exhausted and it’s also hurting us financially.”

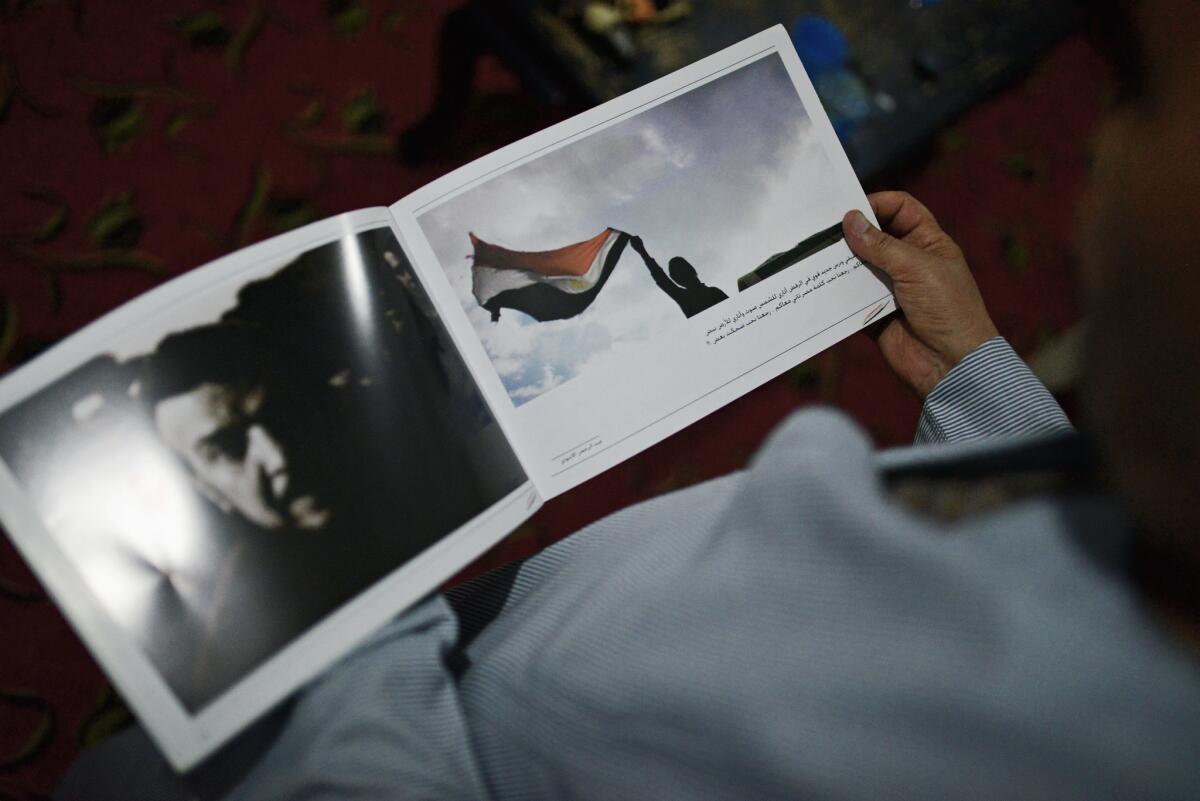

Abou Zeid's father speaks in a calm and composed tone. Sometimes he thoughtfully looks straight ahead as he speaks; other times he looks as though he’s holding back tears.

His wife, their 38-year-old daughter Asmaa and her four young children live in Qena in southern Egypt. They usually make a weekly trip north by train to visit their son in Cairo’s Tora prison, staying in a small plain two-bedroom apartment in Giza’s working-class district of Faisal, where Abou Zeid and his brother Mohamed once lived.

Mohamed, 35, an archaeologist working for the Ministry of Antiquities, moved out of the apartment when he got married — one of the many milestones Abou Zeid has missed during his incarceration. The family continues to rent the place.

Explaining what he missed most about his brother, he pointed at a red armchair and smiled broadly. “He used to sit in that seat and would start working to sell his pictures to [photo] agencies, and we would stay up together until 6 or 7 in the morning,” said Mohamed, referring to the revolutionary years of 2011-13 when freelance journalists like Abou Zeid were in high demand.

“He was my main social life, and we went out together all the time,” Mohamed said.

For their father too, it’s the small moments he’s desperate to regain with his son. “He used to sit in the balcony and I would make coffee for him. Last time [I saw him] he told me he misses my coffee, and he wants to get out so I could make him coffee again and we would drink it together like the old days,” he said.

“We miss everything about him.”

So they wait outside the prison in the hot sun for the chance to see him and buy him the expensive brand of cigarettes he likes. Since before his arrest, Abou Zeid has suffered from hepatitis C and anemia and his parents worry about his health. “His veins are showing from under his skin,” said his mother.

His mother said she remembers warning her son about the risks to journalists who covered the street violence in 2013. She said she told Abou Zeid that he should quit photography when he’s out.

“I told him, ‘When you get out, God willing, stop doing this for good.’ He says, ‘How, Mum? It’s in my blood, I can't.’”

Islam is a special correspondent.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.