Taliban blamed for attack on Bhutto

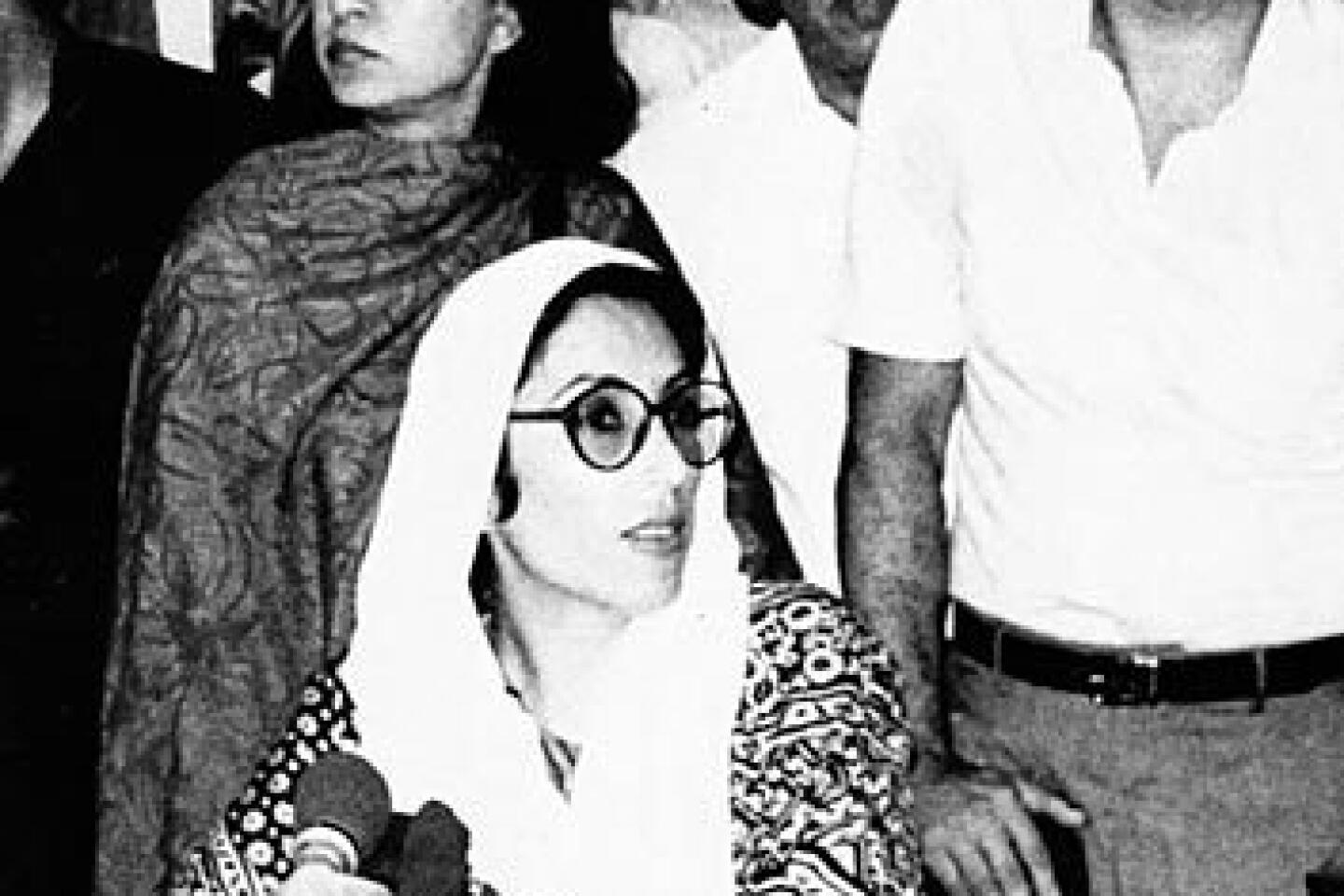

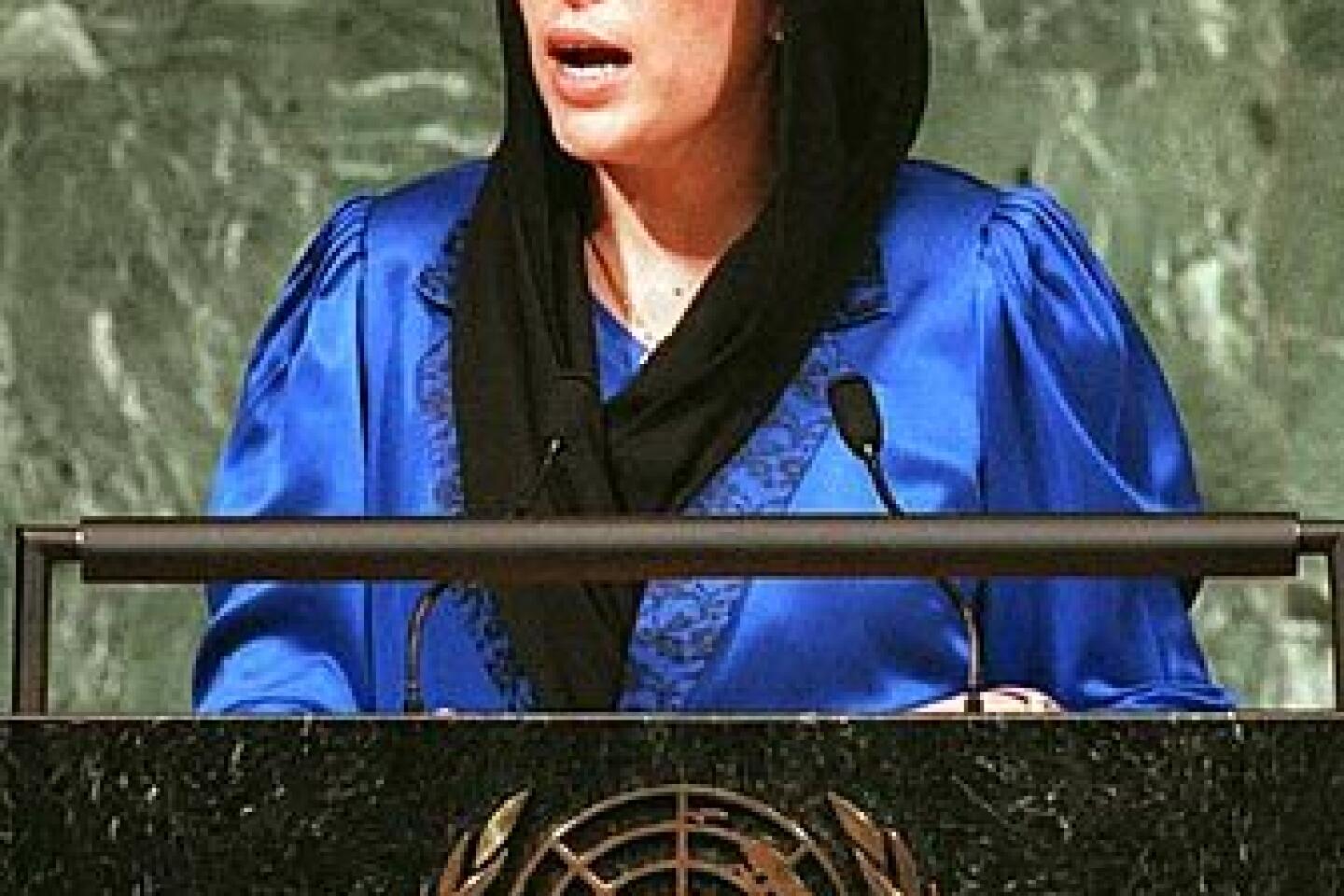

As slain opposition leader Benazir Bhutto was laid to rest Friday in her ancestral village, the government of President Pervez Musharraf blamed her assassination on a Taliban commander and said other politicians also were under threat.

The government cited intercepted telephone conversations in pointing the finger at Taliban leader Baitullah Mahsud, who operates in the regions bordering Afghanistan. It also blamed him for an earlier attack on Bhutto’s convoy in October; Bhutto had said she believed rogue elements within the intelligence establishment or the security forces had colluded with Islamic militants in the bombing.

Mahsud reportedly denied involvement in Bhutto’s death.

Musharraf has been accused of failing to provide Bhutto with adequate security, and in an apparent attempt to deflect popular anger, the government went on to make a startling claim: that she was killed neither by gunshots nor the bombing in Thursday’s attack in Rawalpindi, but instead died of a skull fracture when she hit her head on her SUV’s open sunroof. Her supporters scoffed at the assertion.

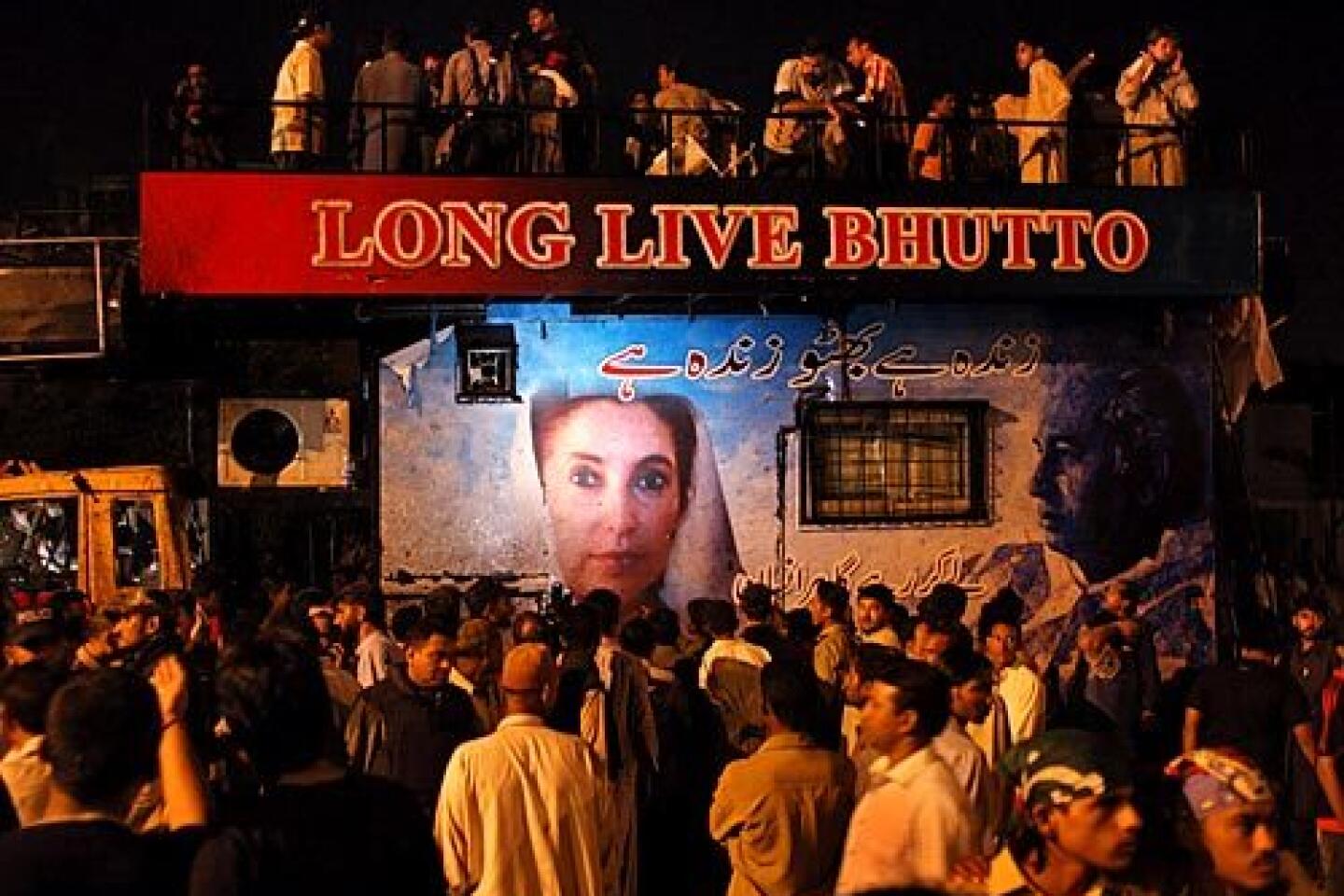

Violence flared in several Pakistani cities, leaving at least 30 people dead during the first 24 hours after the former prime minister’s death. The government deployed thousands of police officers, paramilitary troops and soldiers across the country, giving those in the most volatile areas shoot-to-kill orders against looters and rioters.

For many, the assassination of the country’s best-known political figure was a cataclysmic event, a collective tragedy. “It’s like your Kennedy assassination,” said college student Imran Ashfaq, his eyes reddened as he watched the TV news in a nearly deserted teahouse in Islamabad, the capital. “I’ll always remember this time.”

Much of the country was virtually shut down after the government decreed three days of mourning and Bhutto’s followers called for a general strike. In most cities and towns, streets were deserted and shops tightly shuttered; people stayed home from schools and offices.

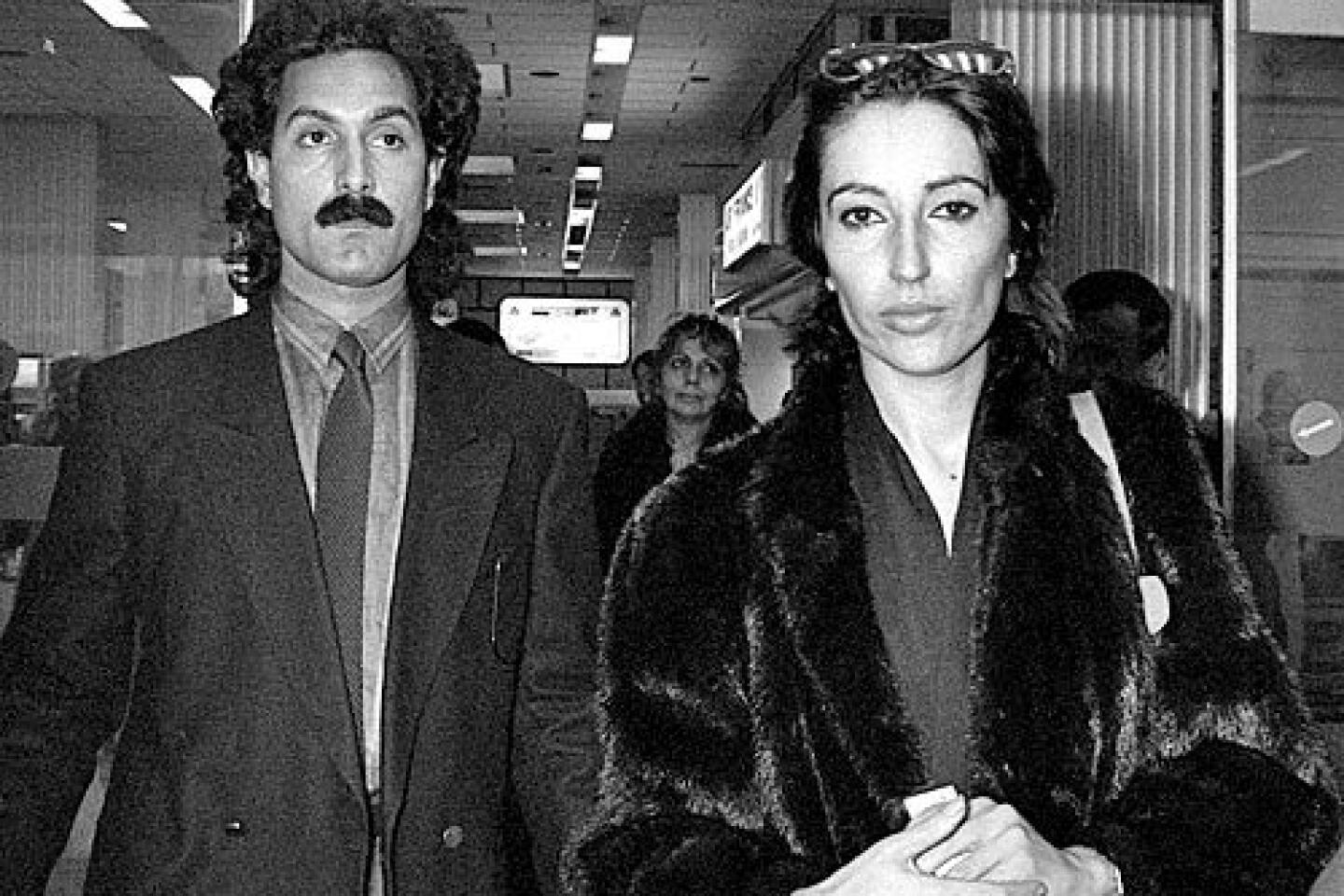

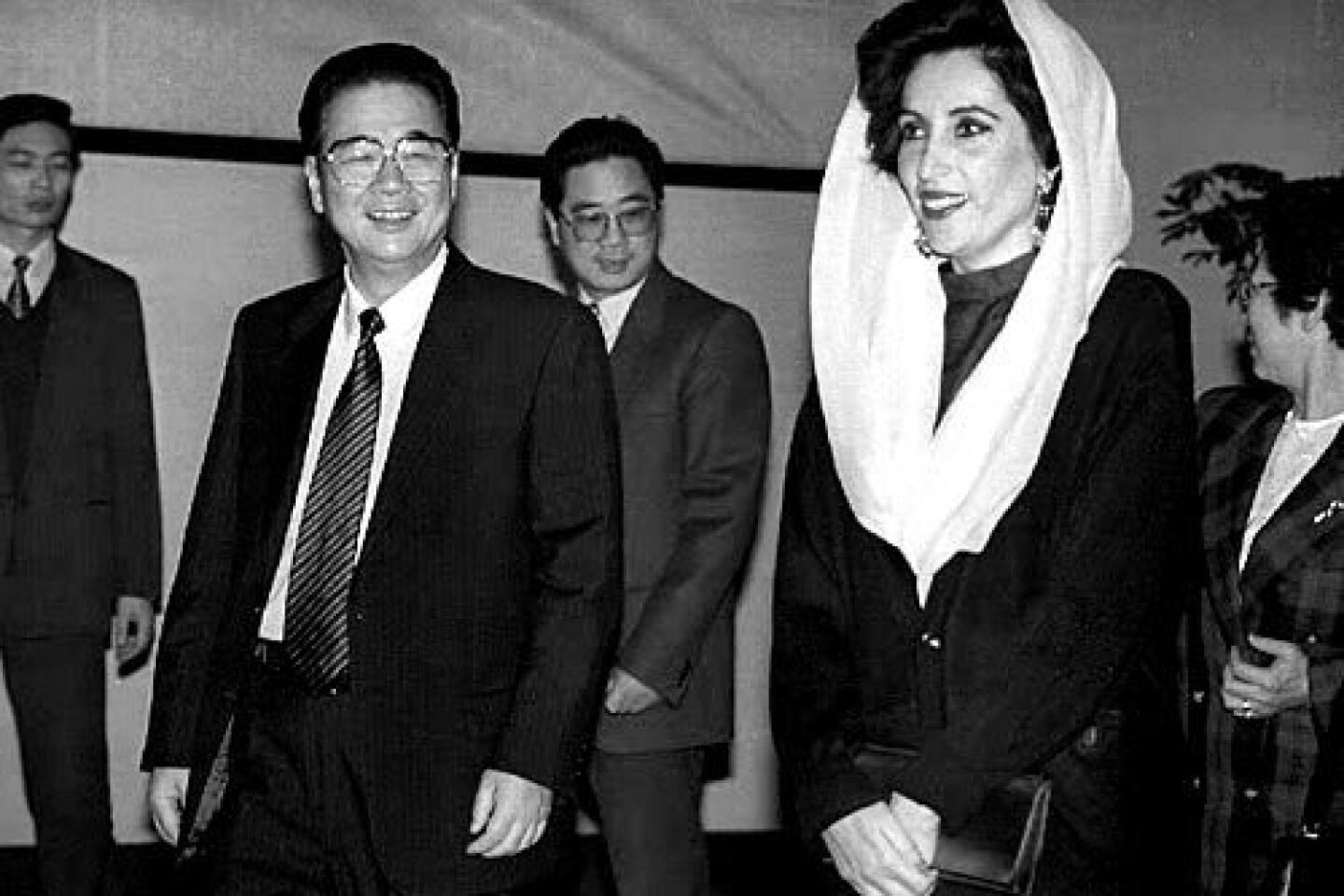

Pakistani television stations played endless footage of Bhutto, showing old black-and-white photos of her as a gawky teen, a glamorous, reed-thin young woman, a dark-eyed mother cuddling her young children.

Banner headlines in many Pakistani newspapers were unabashedly emotional. “Cry the Beloved Country,” read the headline in the English-language paper the News, its white-on-black type stained red as if with drops of blood. “Farewell Benazir.”

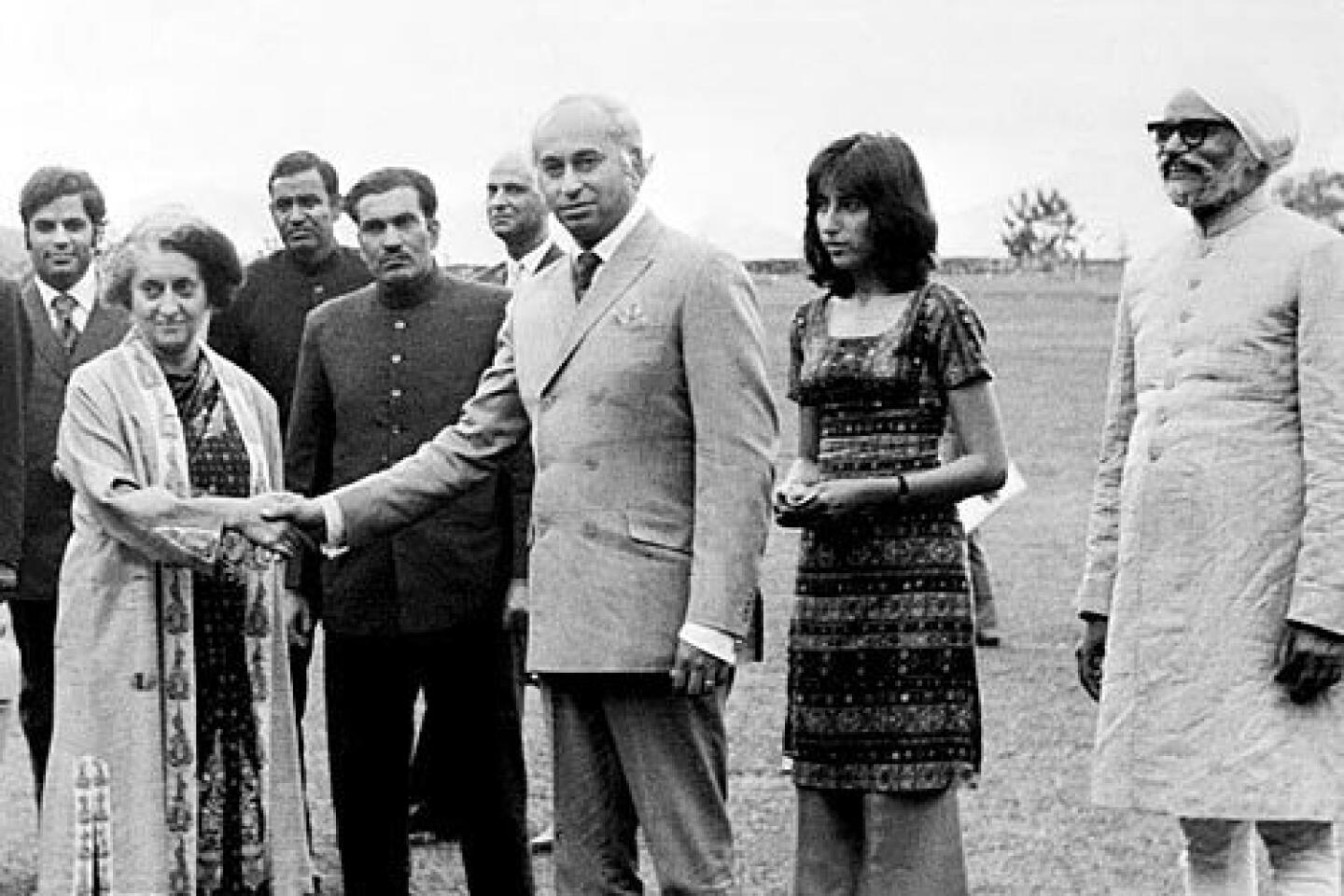

In Bhutto’s remote ancestral village of Naudero, in Sindh province, tens of thousands of weeping, chanting mourners lined the route taken by an ambulance bearing her simple wooden coffin. Her husband and three teenage children escorted the body to the family shrine for burial beside her father, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was hanged nearly three decades ago by the military regime that had overthrown him.

Bhutto’s death threw Pakistani politics into chaos less than two weeks before parliamentary elections that were to have shown the West that this precarious country was moving toward democracy. On Friday, interim Prime Minister Mohammedmian Soomro said the government did not plan to postpone the Jan. 8 elections, despite Bhutto’s death and boycotts announced by other opposition politicians.

The Bush administration has pushed for the elections as a way to signal that this vital U.S. ally in its “war on terror” was moving toward meaningful democracy. In the hours after Bhutto’s slaying, the administration said the elections should go ahead as planned, but on Friday, there appeared to be some easing of that stance.

“We believe that if elections can proceed as scheduled, smoothly and safely, then we would certainly encourage that happening,” State Department spokesman Tom Casey said.

“I think regardless of whether they happen on the 8th or some date shortly thereafter, what’s important is that there is a certainty on the part of not only Pakistan’s political leadership but the Pakistani people that there will be a date certain, that they will be choosing their new government and new leadership.”

The Pakistani Interior Ministry’s assertion that Bhutto had not been hit by either bullets or shrapnel contradicted reports by witnesses and doctors.

Interior Ministry spokesman Javed Iqbal Cheema told journalists that Bhutto, who had been standing up in her SUV to wave to supporters, was fatally injured when the percussion of the blast caused her head to hit the sunroof’s handle. “No bullets . . . were found in her body,” he said.

Incredulous aides to Bhutto rejected the claim. “We all saw what happened to her,” said one senior associate, who spoke on condition of anonymity. After the attack, witnesses described seeing a bloodied Bhutto.

Violence over Bhutto’s killing was concentrated in the southern cities of Hyderabad and Karachi, both in her home province of Sindh, where troops were sent into the streets after furious protesters set fire to cars, buildings, railway cars and fast-food restaurants. Unrest also hit Peshawar, capital of the North-West Frontier Province bordering Afghanistan and a frequent tinderbox.

Government officials said “criminal elements” were taking advantage of the disorder and joining in the violence, looting shops and banks.

Islamic militants were blamed for a bombing that claimed the lives of six people affiliated with a pro-Musharraf party. The attack took place at an election meeting in Swat, a district in the North-West Frontier Province where government forces have been battling Islamic militants. Their leader, a radical cleric named Maulana Qazi Fazlullah, remains at large despite the government’s claim to have “broken the back” of the insurgency in Swat.

The Interior Ministry said the government accusation against Taliban commander Mahsud was based on an electronic intercept of a telephone conversation. Mahsud is a fugitive based in the tribal area along the Afghan border. He is believed to have links to Al Qaeda, and to have issued a threat against Bhutto.

The phone transcript released by the Interior Ministry includes comments attributed to Mahsud about the “spectacular job” by the attackers.

“They were very brave boys who killed her,” Mahsud says, without mentioning Bhutto by name, according to the transcript.

The government did not disclose how the intercept was obtained, or when and where the recording was made.

A purported spokesman for Mahsud who goes by the name Maulvi Omar told the Reuters news agency by telephone today that the militant leader “strongly” denied playing any role in the assassination.

“Tribal people have their own customs. We don’t strike women,” he said.

Mahsud’s forces, mainly locally recruited, operate freely in South Waziristan, the tribal area that has been the focus of fitful attempts by Pakistani forces to root out Taliban and Al Qaeda figures. So great are his reach and influence in the remote, rugged frontier area that he is known among many there simply as the “emir,” or leader. His followers enforce a Taliban-style social code, keeping women from schools or jobs. They have beheaded dozens of tribal leaders accused of colluding with the Pakistani government or the U.S.

Two years ago, Mahsud entered into a truce with the government, promising not to engage in attacks or provide assistance to militants from outside the area, including Al Qaeda-led fighters. But that pact broke down and his forces redoubled their attacks.

Mahsud has publicly denied having threatened Bhutto before she returned to Pakistan. A Pakistani newspaper had quoted him as saying she would be greeted with a suicide attack if she returned.

Cheema, the Interior Ministry spokesman, said authorities had determined that Mahsud was behind the attack on Oct. 19 against Bhutto’s homecoming procession in Karachi on her return from eight years of self-imposed exile.

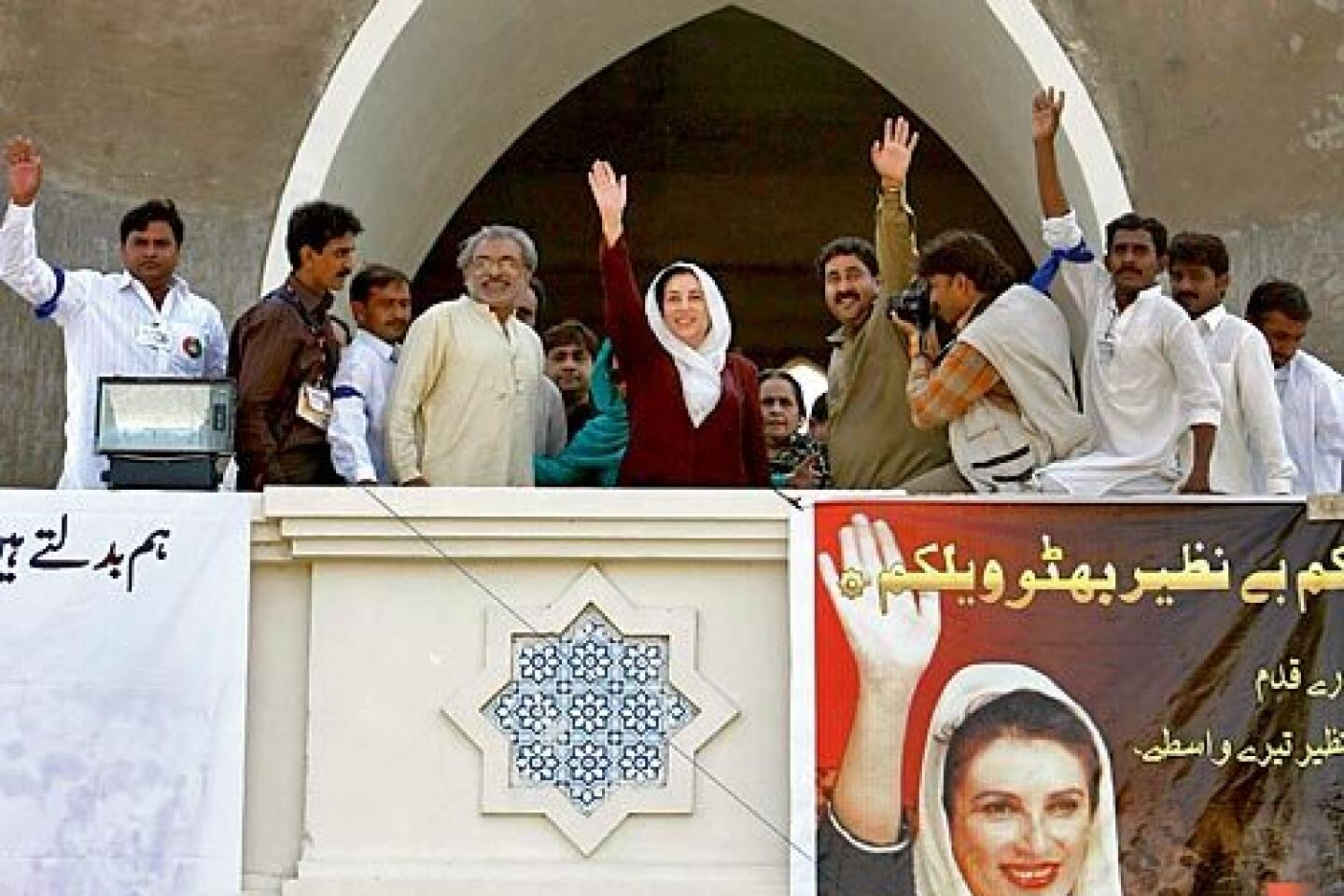

Bhutto escaped injury in that double bombing, but more than 140 people were killed. Until now, authorities had not made any claim to have solved that case, and the timing of their announcement, when angry demonstrators are blaming Musharraf for Bhutto’s death, struck many as suspicious.

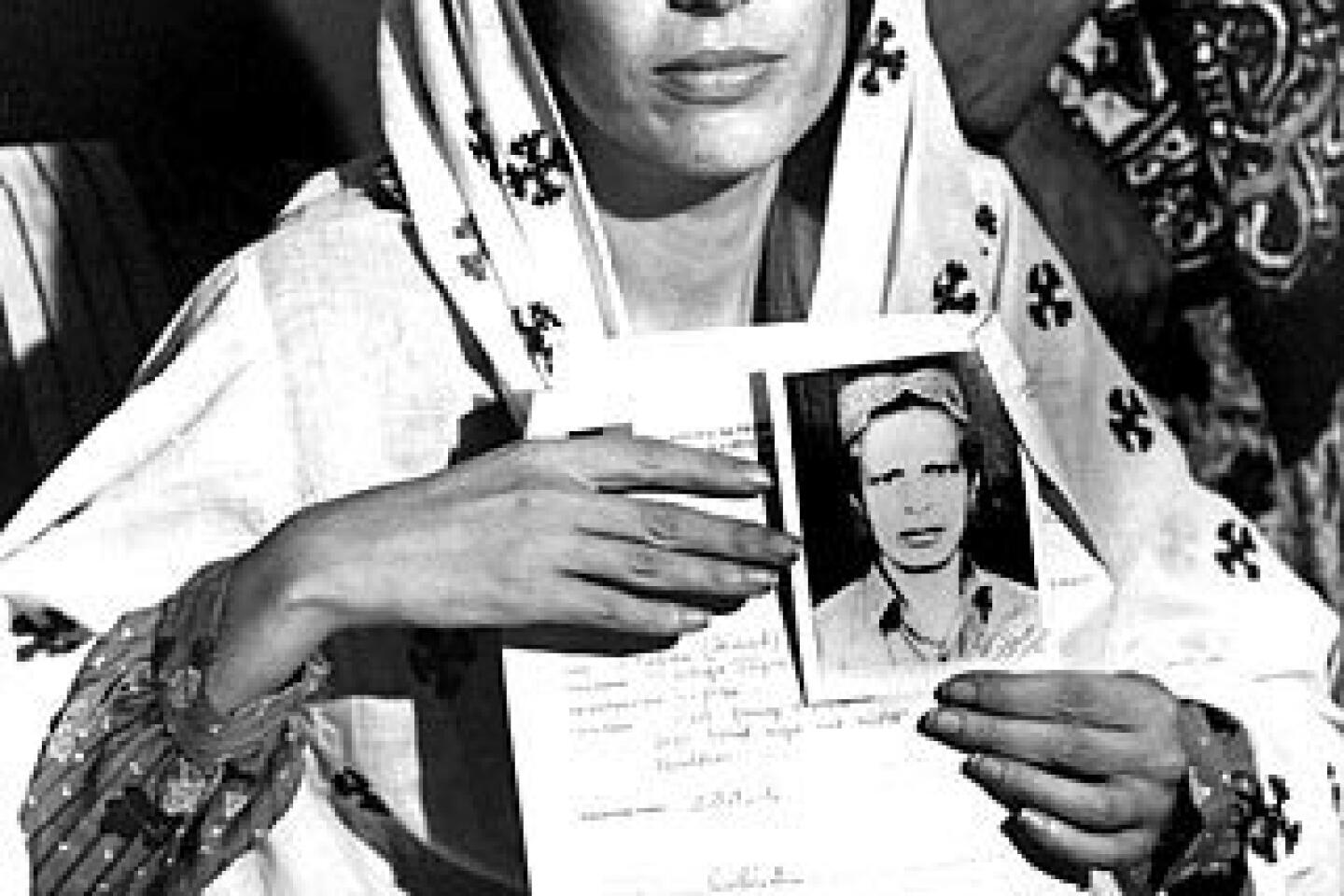

Many of Bhutto’s supporters accuse Musharraf of at least indirect responsibility for her death. Before she was killed, the former prime minister had complained about what she said was insufficient security provided by the government, including a lack of jamming equipment to help forestall remotely detonated bombs.

At the time of Thursday’s attack, Bhutto was standing in her armored SUV, waving at supporters from the sunroof. Witnesses said the vehicle was first hit by gunshots and then, almost immediately, rocked by the powerful suicide bomb.

On Friday, the government disclosed that opposition leader Nawaz Sharif was also under threat of attack. Sharif, also a former prime minister, has been holding mass rallies around the country, including a huge homecoming celebration last month when he returned from exile.

Some political opponents expressed fears that by airing alleged threats against politicians, Musharraf might be seeking a pretext to reimpose a state of emergency, or de facto martial law. The Pakistani leader suspended the constitution and assumed sweeping powers during an emergency decree imposed Nov. 3 and lifted Dec. 15.

Under it, he jailed political opponents, imposed restrictions on independent television stations and fired senior judges whose rulings had angered him.

The deposed chief justice, Iftikhar Mohammed Chaudhry, remains under house arrest in Islamabad.

Although Bhutto’s death triggered an outpouring of rage against the government, most of her followers, especially the poor and downtrodden she had championed, mourned her in silence and solitude.

Early on the morning after her killing, an elderly man was riding his bicycle on a dirt track in the capital, sobbing. He was carrying a heavy load of branches on the back of the bike, and so had to keep both hands on the handlebars and did not even try to wipe away his tears.

Encountering two foreigners, he paused for a moment, nodded, and said simply: “Bibi” -- literally “lady” -- the endearment by which Bhutto was known to all.

Times staff writer Paul Richter in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.