Venezuela may chill drama of Cuba-U.S. relations at Summit of Americas

The White House expected to bask in good wishes at the two-day Summit of the Americas for its historic opening to Cuba, but President Obama will face a problem: Venezuela.

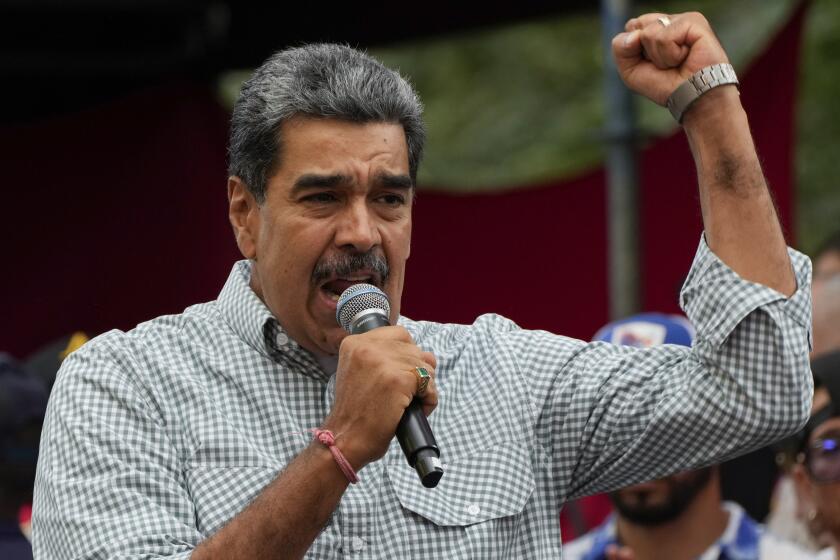

Angered by a White House order that identified his country as a threat to U.S. national security, Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro wasted no time Friday in letting the world know how he felt.

Direct from his landing at the Panama airport, Maduro hurried to the neighborhood most heavily damaged by the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama. There, as other presidents spoke in a fancy downtown hotel ballroom, Maduro paid homage to the “thousands of victims” of the military action that ousted then-dictator Gen. Manuel Noriega and laid a wreath in their memory.

“This is no longer a time for imperialism and threats,” Maduro said, surrounded by cheering students and other supporters. “This is a time for peace ... and respect for nations.”

When U.S. forces invaded, dozens of buildings were destroyed in the El Chorrillo slum where a key Panamanian military installation was located. Estimates of the death toll range from several hundred people to 1,000, with others injured, arrested or missing after the short conflict.

Maduro met with survivors, hugging a woman who said her son was killed, and promised to carry their demands for justice directly to Obama.

He also planned to hand-deliver to the American president a petition with 10 million signatures urging cancellation of the executive order that placed sanctions on several Venezuelan leaders. Other leftist governments, such as Cuba, have mounted a similar petition drive.

For Maduro, who has used the U.S. move as a way to rally support at home, the gesture would mirror that of his predecessor, mentor and hero, the late Hugo Chavez, who presented Obama with a book at the 2009 summit documenting what was called the pillage of Latin America by U.S. and European powers.

The sanctions announced by the administration classify Venezuela as a threat to U.S. national security. White House officials have downplayed those terms as “pro forma” language used in similar executive orders. But they view the situation in Venezuela as a major concern and hope to find allies at the summit to promote political reconciliation there.

The sanctions target seven Venezuelan officials accused of violating human rights.

“We don’t have any hostile designs on Venezuela,” Ricardo Zuniga, director of Western Hemisphere affairs for the National Security Council, told reporters before the gathering.

“A number of governments have expressed concern over the arrest of elected leaders by the government of Venezuela. We think it’s important that we continue to work together to reaffirm regional values on democracy and human rights.”

In reality, though, most Latin American nations have remained relatively quiet on Venezuela, in part because of their own domestic troubles or because of their reliance on Venezuelan oil.

Vice President Joe Biden met briefly with Maduro in January on a visit to Brazil, where he expressed the administration’s view that the relationship between the countries could be far better if Maduro took steps to release political prisoners, engage with his opposition or invite international observers into Venezuela.

“So far that’s not what has happened,” said an administration official who requested anonymity while discussing the administration’s efforts in the region. “The door remains open for us; we look forward to engaging in a conversation with Venezuela. But the ball is in their court.”

If Obama receives Maduro’s petition, some have suggested that he respond by presenting the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights.

This week, Thomas Shannon, counselor to Secretary of State John F. Kerry, went to Caracas to meet with senior Venezuelan officials in an effort to calm tension before the summit. It did not seem to have much effect. On the eve of his departure to Panama, Maduro presented one of his trademark marathon speeches, rallying his supporters with anti-U.S. rhetoric.

“A new America has been born,” he said. “Our America.”

It is not yet clear how much of a following Maduro will muster here. Cuba, allowed to attend the summit for the first time, may not want Venezuela to steal the spotlight completely. Contact between Obama and Cuban President Raul Castro is a much-anticipated moment in the summit, their first personal “interaction,” as the White House puts it, since the December announcement of renewed diplomatic ties between the countries after more than half a century.

“My guess is the Latin Americans in general will not want to follow Maduro over the cliff. I don’t even think that the Cubans will want Maduro to take the summit over the cliff,” said Richard Feinberg, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution’s Latin America Initiative.

“I think the Cubans will say to the Venezuelans, ‘Yeah, look, you can have your moment in the sun, but this is really our fiesta and we want to have the headline be the photo op showing harmony and progress rather than divisiveness.’”

Officially, the theme of the summit, formally opening Friday night, is prosperity and equality, two elements that rarely go hand-in-hand in the Americas.

Obama, speaking at a parallel summit for big business, said integration was the key to the region’s fair development. He symbolically made that point by visiting the Panama Canal and praising Panama’s efforts in “bridging two continents and bringing the hemisphere together.”

Obama also spoke of the economic development of the region, contrasted with a period 30 years ago when, he said, there tended to be two forms of economies: a statist system or a free market.

In his single allusion to Venezuela, he said that now, everyone in the region has “a practical orientation. Maybe not everybody, but almost everybody.”

The audience laughed.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.