Many Iranians pessimistic about reaching deal to ease sanctions

As a Monday deadline looms for Iran and global powers to craft a nuclear accord, the official media here are already priming weary citizens for the possibility that no agreement will be forthcoming. Commentators leave little doubt who will be responsible.

“America should be blamed for any failure,” an anchor on state-run television advised viewers Friday.

At Friday prayers in central Tehran, Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati ticked off a few words of advice for negotiators in Vienna.

“Do not be scared of America,” the powerful cleric counseled Tehran’s team in the Austrian capital. “Do not accept humiliation.”

Speculation was rife Friday that an extension could be in the works after four days of negotiations with no apparent breakthrough on disputed points, including future nuclear enrichment levels for Iran and a schedule for lifting economic sanctions. Both sides have been cool to the idea of an extension, which would publicly signal stalled progress on one of the major security issues on the global agenda.

After almost a year of contentious debate, with Iranians being bombarded with obscure details about spinning centrifuges, uranium enrichment processes and the idiosyncrasies of heavy water reactors, many citizens appear to have lost hope that a comprehensive accord will emerge by Monday. A sense of pessimism seems to have replaced last summer’s buoyant confidence that things could be looking up for the nation’s sanctions-battered economy.

“I’m fed up with so much talk and no results,” said Akbar Baseri, 42, who was visiting a print shop here in the capital with his two children. “The negotiating team is wasting time and money, and at the end of the day people will have to pay the soaring prices.”

Many Iranians are keen for a deal that could help tame inflation and yield more jobs, especially for young people with college degrees but few prospects. But the prolonged talks and the profound divisions have left many discouraged.

“I have no hope for a deal,” Reza Hasani said, sipping coffee at an upscale cafe in north Tehran. “The supreme leader has the final say, and he does not want to compromise with America and its allies.”

Indeed, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the ultimate authority on policy decisions, recently embraced the concept of a “resistance economy,” one shielded from sanctions and other outside economic pressure. Many perceived that as a hint that a deal was doomed, even though the supreme leader has approved of the talks and hailed Iran’s negotiating team.

President Hassan Rouhani, a moderate cleric and longtime government insider, was elected in 2013 on a vow to undo sanctions and help end Iran’s international isolation. The nuclear negotiations are a linchpin of that strategy. Without a deal, Rouhani’s entire modernizing agenda, including enhanced personal freedoms and rapprochement with the West, could be threatened, as could any hope for a second four-year term.

Even if an accord is reached, analysts say, it seems probable that sanctions relief would be limited at first and unlikely to produce a quick turnaround in the economic fortunes of most Iranians. Popular disappointment may be inevitable.

“President Rouhani is a loser in the event there is no deal, a bad deal or the extension of talks,” noted Mojgan Faraji, a political analyst in Tehran. “He either miscalculated or he knew his promise was impossible and he deceived the people to win votes.”

The president’s hard-line foes have mounted a spirited rear-guard action against any nuclear accord.

For many conservatives, the talks in Vienna are a smokescreen for nefarious Western aims that have nothing to do with nuclear proliferation. Many view sanctions as one component of a broader, U.S.-led strategy to undermine and ultimately bring down the Islamic Republic.

In pre-sermon comments Friday from the religious city of Qom, Brig. Gen. Hussein Salami, deputy commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, called on the negotiators to spurn “excessive demands of enemies,” the Tasnim News Agency reported.

Powerful interests, including Revolutionary Guard commanders and members of the clerical establishment, see a nuclear deal and any possible detente with the West as a betrayal of the 1979 Iranian Revolution — and a threat to their interests.

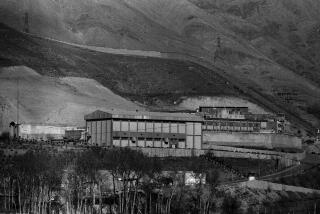

Sanctions-busting — the smuggling into Iran of products ostensibly not available because of sanctions — has become a lucrative business. Conservatives repeatedly point to the nuclear program as a source of pride, even as others contend that it has brought more problems than benefits, contributing little to the electrical grid.

“We have spent billions of dollars for nothing, with lots of political and economic costs for the nation,” said Sadegh Zibakalam, a political scientist at Tehran University who is among the few willing to make such comments on the record.

Iran’s leadership has long disavowed a drive to build nuclear arms, insisting that its program is strictly for energy generation and other peaceful purposes. However, the United States and its allies, including Israel and Saudi Arabia — which both view Iran as a major regional rival — suspect that Iranian authorities see nuclear weapons capability as a hedge against external attack.

The stated goal of the Vienna negotiations is to craft a comprehensive blueprint ensuring that Tehran’s nuclear efforts are strictly for peaceful use.

In recent days, both supporters and opponents of a nuclear deal have ramped up the rhetoric. The Iranian news media have covered the run-up to the final round of talks like the days before a championship football match.

“We hope Nov. 24 will be a day for national celebration,” blared the headline on a moderate daily favoring a deal by Monday’s deadline. In contrast, the Kayhan newspaper, a voice of hard-liners, warned that “without lifting all sanctions, the deal is invalid and nullified.”

For many Iranians, the intricacies of the nuclear issue have become overwhelming and tedious.

“The talks are so complicated that I don’t dare to make a prediction,” said Hossian, 50, a civil servant who declined to give his last name for privacy reasons. “I’m too busy trying to make a living for my family.”

Special correspondent Mostaghim reported from Tehran and Times staff writer McDonnell from Beirut.

Follow @mcdneville on Twitter for news out of the Middle East

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.