CIA torture report not likely to result in reforms or prosecutions

A Senate committee report describing the CIA’s torture of detainees and accusing the agency of lying to top White House officials about its secret program may be the most detailed excavation of government officials’ misconduct in years. Still, the prospect that Washington will respond with major reforms, legislation, firings or criminal prosecutions was slim.

The day after the release of the report’s executive summary, the White House dodged questions on whether President Obama agreed with its core findings and suggested he already has done all he believes to be necessary to prevent a repeat of the brutal interrogations that he said “constituted torture in my mind.”

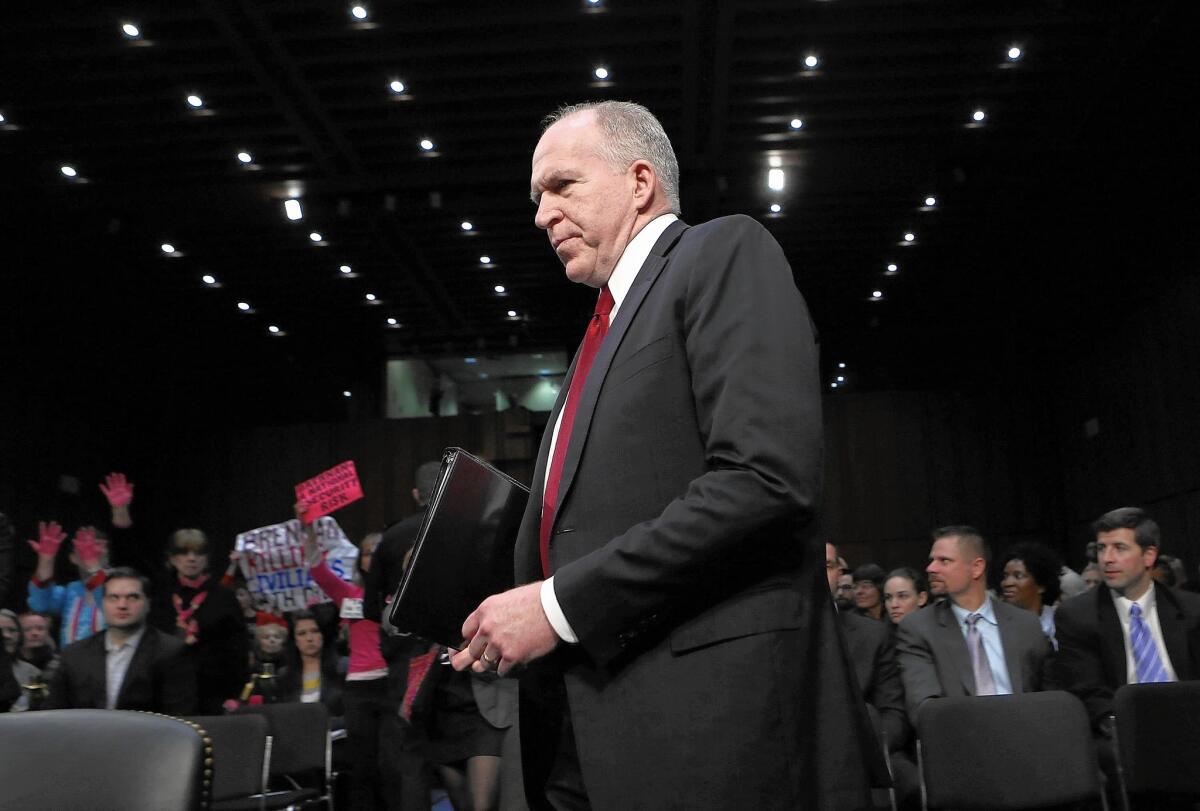

Amid a fresh call for a major shake-up at the highest levels of the CIA, the White House expressed support for agency Director John Brennan, who was the deputy executive director in 2002 when the interrogation program was designed and implemented.

The Justice Department defended its decision not to prosecute those involved, saying the report would not trigger reconsideration.

And in Congress, where lawmakers split along party lines over the accuracy of the findings and the wisdom of releasing the 500-page redacted summary, there were few signs of momentum behind legislation.

The apparent stasis after what some experts described as a seminal retelling of a dark chapter in U.S. history was expected to disappoint those who have long pushed for public accountability for the agents and officials involved.

“No one has been held to account. Torture didn’t just happen.... Real actual people used torture,” Democratic Sen. Mark Udall of Colorado said Wednesday on the Senate floor as he called for Brennan’s resignation and a purge of top CIA officials. “What’s to stop the next White House and CIA director from supporting torture?”

Still, the prevailing approach among the White House and Republicans primed to take control of key committees in Congress was that the report is more useful as catharsis than a call to action. The fixes have already been made, they contended.

The White House emphasized that Obama signed an executive order banning torture as one of his first acts as president. He also ordered the Justice Department to review the treatment of detainees and formed a task force to review practices of transferring prisoners to other countries. A CIA inspector general also has reviewed the program.

“The commander in chief concluded that the use of the techniques that are described in this report significantly undermined the moral authority of the United States,” White House spokesman Josh Earnest said.

Similarly, the Justice Department has cast the matter as a closed case.

A department official said Wednesday that federal prosecutors will not reopen their investigation of whether criminal laws were broken by CIA guards and interrogators for mistreating detainees.

That review began in 2009 when Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. directed an investigation to determine whether the CIA mistreated detainees at secret “black sites” who were tied to the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the United States. The review generated two criminal investigations, but Department officials “ultimately declined those cases for prosecution” because of insufficient evidence, said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Prosecutors have read the Senate committee’s full report and “did not find any new information” that would warrant reopening the case, the official said.

Human rights advocates have contended that the investigation was too narrow. At the start, Holder made it clear that his department “would not prosecute anyone who acted in good faith and within the scope of the legal guidance” given by the George W. Bush administration that approved some of the interrogation techniques.

The American Civil Liberties Union, among other groups, is calling for the Justice Department to appoint a special prosecutor and hoping Senate Democrats will raise the issue at confirmation hearings for U.S. Atty. Loretta Lynch, Obama’s choice to replace Holder. Advocates are pushing lawmakers to put Obama’s executive order into law, a recommendation made in the report, as well as mandate smaller changes that would shift the culture at the CIA.

An Intelligence Committee aide said Wednesday that such recommendations will be released in coming days.

Sen. Richard M. Burr (R-N.C.), who will replace Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) as head of the Intelligence Committee in January, said this week that he has no plans to revisit the findings of the Democratic-led report.

“We’re going to focus on real-time oversight. We’re not going to be looking back at a decade trying to dredge up things,” he said.

Outgoing House Intelligence Committee Chairman Mike Rogers (R-Mich.) has also strongly criticized the report.

Even one of the few Republicans to support the Feinstein-led review, Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.), suggested Wednesday that legislation in the new year to address findings of the report was unlikely.

“All of this stuff happened before we passed the Detainee Treatment Act,” he said of the 2005 law that prohibits “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment” of detainees. “We cured it.... Now it’s against the law.”

Without a legislative response, the Senate inquiry would stand apart from its two comparable investigations of the past, said Loch K. Johnson, an expert on the CIA relationship with Congress. The Church Committee inquiry of CIA abuses in the mid-1970s and the Iran-Contra hearings of a decade later resulted in legislative reforms, said Johnson, who was a top aide on the Church Committee.

Neither of those investigations led to prosecutions, he noted.

“The attitude has been that the shame of it is a powerful thing,” he said.

Times staff writers Brian Bennett and Richard A. Serrano contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.