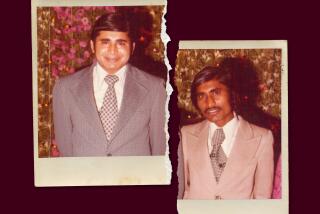

One of Few to Kick Habit Tells About Life on the Edge

Mike Franz was 18 when he first started shooting heroin during a 16-month stint in the California Youth Authority, where he was serving time for smuggling three jars of amphetamines over the border from Mexico.

“I had been selling and taking speed and crystal since the age of 16, so when a guy in jail offered me some heroin, I gave it a try,” Franz recalled.

It was the beginning of a 17-year habit, an agonizing odyssey that sent Franz into four drug programs, two mental institutions, six county jails, three penitentiaries and eight hospital emergency rooms for treatment of overdoses.

He committed burglaries, fenced goods stolen by others, and ripped off his family and friends to maintain the flow of heroin into his veins.

Today, Franz is a tan, fit 37-year-old man with a gentle voice and an inclination to smile. After two years of total abstinence from drugs, the program manager of the MITE detoxification program is a sharp contrast to the person who once was willing to “do anything and betray anyone” to get a fix.

Before he started using drugs, Franz, who grew up in a middle-class neighborhood of Villa Park in Orange County, said he “ran track, got decent grades and stayed out of trouble.”

That changed. After he started using drugs such as amphetamines, he was sent to the California Youth Authority, where he was introduced to heroin.

When Franz got out a few months later, the man who had given him the heroin--a dealer from Hollywood--asked him to begin selling the drug.

“The first time he fronted me a quarter ounce of stuff and I ended up with $200,” Franz said. “The next time I just broke even. With the third batch I ended up owing him money.”

Within a month, Franz stopped taking speed and begun to feed his heroin habit full-time.

“The first few times I tried heroin I didn’t even like it,” he remembered. “I kept getting sick and throwing up.

“But while I was in jail all my friends had begun doing heroin, so I said to myself that there must be something really good about it. Then later I started getting fixed real well and forgot everything else.”

As his need for the drug swelled into a habit of several hundred dollars a day, Franz said, he became unreliable even as a drug dealer.

“Essentially, heroin users are not good people to do business with, since they’ll do whatever (drugs) they can get their hands on,” he said. “Rather than thinking over the long term, the junkie’s time horizon tends to go only as far as the next time he is going to shoot up.”

The only time the cycle was broken for Franz was when he was put in jail and his access to heroin was severed.

Franz said that he used to be “almost grateful” when his offenses began to mount and he was sent to jail.

“You would get so tired of scraping up the money all the time, and you knew that if you went to jail you would get healthy.

“Each time I got clean, I swore to myself that I would stop for good. But the minute I was back out on the street, I would start the same cycle all over again.

There were at least eight times when he overdosed--either by misjudging the strength of the drug or by combining heroin with other drugs--and he was rushed to hospital emergency rooms. Each time, he said, “they were able to bring me back through antidotes.

“For a long time, I was absolutely convinced that I would die with a needle in my arm,” Franz admitted. “You know it’s sick, but whenever someone (an addict) does die, the first question people ask is, ‘Where did they buy their stuff?’ since they know it must have been good.”

A string of misfortunes brought Franz to the point where he decided to enter the MITE detoxification program and give up heroin for good.

In 1980, Franz was sent to Chino State Penitentiary for two years for burglary and receiving stolen goods. Because his cellmate was a dealer, he was able to maintain his habit.

“The penitentiaries had really changed since the last time I was there,” he said. “For one, I didn’t have the crutch of knowing I was going to get clean anymore. Also, the guys there seemed younger and more violent.”

While in jail, Franz watched his closest friend die in his arms after being beaten by other prisoners with golf clubs during a race riot. After serving his term, Franz moved in with his sister in Ocean Beach.

He began a methadone maintenance program, although he said it did not prevent him from continuing to shoot up.

“In my opinion it’s poison,” he said about methadone. “I think they should blow up all those . . . clinics. Even though methadone reduces the frequency that you have to take it, you still remain tied to that drug.”

When Franz’s sister, a reformed alcoholic, discovered that he was not keeping clean, she kicked him out of her house, and he spent several weeks sleeping on a piece of cardboard thrown under a bush. After being caught for two more burglaries, Franz decided to enter MITE.

Franz today refrains from using any drugs, including alcohol and marijuana, because “they would be just a roundabout way back to heroin.”

Putting the 17-year odyssey into heroin addition to an end has made Franz one of the few addicts to beat the dismal odds they face when trying to quit.

“I guess I got to the point where I just didn’t have any other choice,” Franz said.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.