Classroom Computer Program Pays Off in Fun for Students, Profit for Teacher

When each 21-minute session in the computer room at Capri Elementary School ends, the children groan in disappointment.

Loudly. Collectively.

It’s not quite rebellion, but it’s not the kind of thing you expect to hear in elementary school classrooms when a lesson ends.

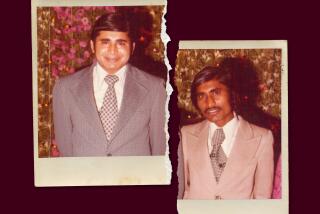

The groans are music to Cecil Hannan’s ears. Hannan, chief executive officer of a fledgling corporation, is testing an instructional computer program at Capri and two other elementary schools in Coronado and Vista. And he believes the children’s dismay means his multimillion-dollar project is on the right track.

Of course, there is other evidence. The Capri school’s computer lab has been visited by educators from the Virgin Islands, Washington, Texas, Missouri and communities in California, to name a few.

Hannan, who said he spent five years and about $6 million developing the $36,000 software system, believes he will have 40 of them installed in schools around the country when classes begin in September. That number will increase to 100 by January and 1,000 in two years, he predicted.

The San Diego Unified School District, for example, is leasing two of his systems for city elementary schools. Schools in Chicago, New York, Seattle and Texas will use his computer system beginning this fall, Hannan said.

His privately held firm, Education Systems Technology Corp., is now worth $12 million, Hannan said. In two years, it will be worth $100 million, he predicted.

“With a little bit of luck, I’m going to make a lot of money,” said the former vice chancellor for the San Diego Community College District. “But that’s not my primary motive. My primary motive is to help kids learn.”

Teachers believe that the ESTC system may do that too, though some experts in the field warn not to expect too much from computer-assisted instruction systems like Hannan’s.

The ESTC system divides the reading and math curricula for kindergarten through sixth-grade into small units, teaching and reviewing each concept with splashy graphics, much repetition and endless praise.

Students must demonstrate mastery of a concept before the computer will allow them to go on to a new one. Printouts allow lab technicians--paid by ESTC--to monitor each student’s progress.

In addition to keyboard communication with the computer, students listen on headphones to computer-generated commands--in- cluding short tunes of congratulation when they choose a correct answer--and talk to the unit through a microphone. They can also move images on the screen with a “mouse.”

The result is a highly individualized instructional method that can be tailored to students’ learning speeds and needs--creating, in effect, an electronic one-room schoolhouse.

The programs are designed to supplement instruction students receive from teachers--not replace the teachers. People still provide the best teaching, Hannan and other educators believe, offering human contact that computers cannot.

Sue Coyle, the principal at Capri, said that in the year that her fifth-grade students have been using the system, their reading and math scores on the Comprehensive Test of Basic Skills have increased an average of nine points on each test.

Hannan believes his system will be especially useful for students who have difficulty learning, and troubled students who might be prone to dropping out. A similar, much older, system named Plato is used in the Sweetwater Union High School District in an experimental project that is luring dropouts there back to school.

“There is no reward for being the class clown,” Hannan said. “There is no reward for failing to learn.”

A vice chancellor for the San Diego Community College District for eight years, Hannan founded ESTC with Mesa College English teacher Burl Hogins. He said he has been working on the idea for about five years, although the Sorrento Valley-based corporation founded with the help of venture capitalists is about 18 months old.

Hannan and Hogins wrote the initial curriculum, then hired experts to review it. Then, one hundred teachers they hired divided the curriculum into individual lessons. Screen designers and artists then prepared the millions of frames seen by students on their computer screens.

Although the men may have spent more time and money developing their system than other manufacturers and the system appears to have generated rapidly-growing interest, such computer-assisted instruction projects are not new or unique.

According to Bernie Dodge, associate professor of educational technology at San Diego State University, about a dozen major companies and hundreds of small manufacturers are producing similar products. Computer-assisted instruction is about 20 years old, he said.

Research shows that computer-assisted instruction is no better and no worse for students than receiving the same kind of training from an equally capable teacher, Dodge and other experts said.

At a cost of $36,000 to lease the ESTC system, plus about $70,000 to buy the hardware, the package is fairly costly for a school district the size of the Encinitas Union School District, where the Capri school is located, Rybolt said. Another drawback is that the system does not involve teachers very often, because ESTC provides lab technicians to help students, he said.

But Dodge and Colin MacKinnon, coordinator of computer education programs at United States International University, worry most of all that school systems are becoming locked into using such systems as “electronic workbooks” for drill and practice, instead of teaching students to use computers as learning tools. The future of computer-assisted instruction, they said, will be the latter.

ECST and comparable systems are “going to be a third of what goes on with educational technology,” Dodge said. “It’s an important third. It’s training. It’s mastering measurable skills that can be identified. The other two-thirds is using the computer as a tool to explore the outside world.”

“I would invest,” MacKinnon said. “But I wouldn’t make it a long-term investment. I think you’re going to see it wane.”

Hannan, who said his program does teach higher order thinking skills, sees an expanded future for his product. He plans to begin writing programs for junior high and high school students.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.