Fade In on AFIFEST’s Wlaschin : Movies: The festival director is optimistic about the future of the L.A. event, despite the tough economic times.

His world stretches around the globe: from Rangoon to Walla Walla, Liverpool to the Riviera, from Beirut and Bombay to Budapest and Bangkok.

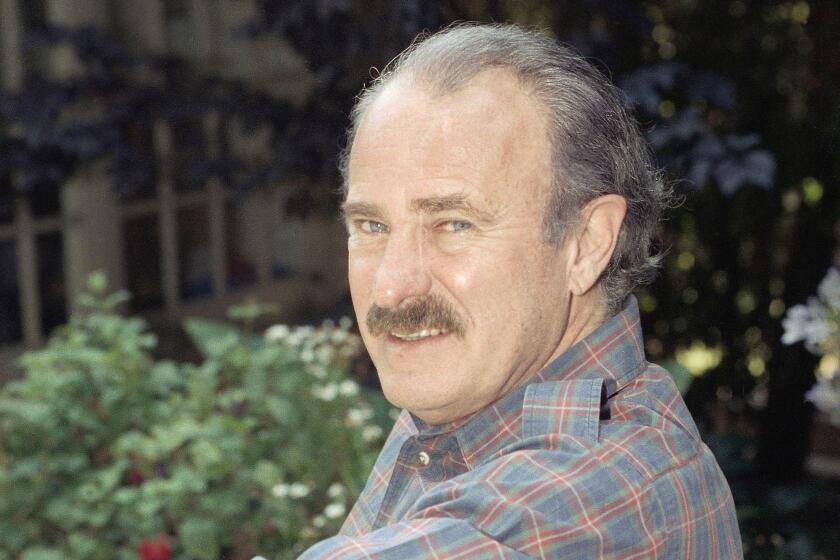

But though he’s the director of Los Angeles’ American Film Institute Film Festival (or AFIFEST)--which begins its seventh season Thursday at the Laemmle Sunset 5 in Hollywood, with a gala screening of the restored 1961 “El Cid”--Ken Wlaschin started out as a hometown boy from the Heartland. Scottsbluff, Neb. (pop: 14,000), to be exact.

“It’s one of those towns that Californians are fleeing back to these days,” Wlaschin says of Scottsbluff. Scottsbluff will never claim Wlaschin again, but he still looks and talks a little bit Midwest: tall, bright-eyed and gray-bearded, with that same snappy but mellow Midwestern twang familiar to us from Johnny Carson, Henry Fonda and other Nebraskans.

Yet, for the past seven years, Wlaschin has been saturated by all the sights and sounds of the planet’s movies. Programming AFIFEST, he personally selects each of the more than 150 films that make up the festival. And that’s not all. Wlaschin also programs the AFI’s National Film Theater at Washington’s Kennedy Center (about 1,000 films annually), AFI’s Video Festival (another 150 works), the AFI Women’s Fest (20) and the Festival of the Americas (30). Before the European Market withdrew its sponsorship, he also did Eurofest (25 more). That’s a staggering annual movie-watching diet--but it doesn’t take into account the movies he sees non-professionally, for fun. Or all the films he saw and didn’t pick. “Much more than people think,” he smiles.

This seemingly insatiable cinematic appetite is fed by a background that is, like most buffs’, eclectic. In the 1960s, Wlaschin wrote or co-wrote two thrillers, “To Kill the Pope” (which may reflect his Catholic boyhood) and “The Italian Job” (filmed with Michael Caine and Noel Coward in 1969). He also concocted “The Bluffer’s Guide to the Cinema,” a handy guide to name and term-dropping for the cinematically semi-literate.

His path to L.A. was international. Educated at Dartmouth, the University of Ireland in Dublin and the University of Poitiers in France, Wlaschin became programmer for the National Film Theater in London and then took over London’s Film Festival when Richard Roud left to devote full time to New York’s. Los Angeles beckoned in 1984, with Wlaschin taking over the last two troubled years of FILMEX. Then, after a year’s hiatus, the phoenix of AFIFEST bounded up from the ashes.

Asked about AFIFEST’s current status, Wlaschin is positive. But guarded. We are, after all, in a recession, many of the old arts funding sources have dried up or thinned out, and AFIFEST’s main sponsor, the Interface Group, left after the 1990 festival, not to be replaced. “Like all the festivals and nonprofit cultural organizations, we have funding problems,” Wlaschin admits. “They’re endemic, I think, to every single cultural organization in the United States. The trouble is that, when you’re in a recession, sponsors have to spread their money thinner and thinner.

“The actual budget on AFIFEST is in the neighborhood of $400,000; that doesn’t count the year-round operation. And that’s, relatively speaking, minimal for an international film festival.”

Minimal? “Well, Berlin costs $6 million. Venice is part of the Biennale--an overall arts package--but I would assume they’re in the $3- to $4-million range. Cannes (which shows 600 to 800 films, and which Wlaschin no longer attends, due to AFIFEST conflicts) costs $6 million--and they get it mostly from the French government. The Tokyo Festival gets $8 million.”

*

And what about London, where for 15 years, Wlaschin ran both the London Film Festival and the British Film Institute’s National Film Theater? “In Great Britain, the BFI gets, from the government, 20 million--about $33 million, now--a year, to subsidize all its operations. The BFI’s National Film Theater alone operates with a subsidy of somewhere close to a million pounds a year. The American Film Institute, in a rather richer country, gets $1.5 million from the government; that’s down to $1.2 million now.”

Of course, in America, there are numerous business organizations to take up the slack; they’ve assumed the mantle of the old European aristocracies. But, in Los Angeles, Wlaschin points out, there’s a difference. “The movie studios, traditionally, in Los Angeles, have not supported the arts. And not just film (festivals): They don’t support theater or music or anything else. . . . It’s interesting. Traditionally, in most large cities, it’s the largest industries that support the arts.”

*

Lazy writers tend to stereotype foreign-film enthusiasts as esoteric, tea-sipping elitists, dripping with ennui, jargon and condescension. But Wlaschin is far more a movie populist. Asked once for a personal all-time Top 10 list, his top two choices were both French (Vigo’s “L’Atalante” and Dreyer’s “Passion of Joan of Arc”). Some others came from foreign countries (Angelopoulos’ “Travelling Players,” Ozu’s “Tokyo Story” and Wajda’s “Kanal”). But there were also, nestled among his favorites, an MGM musical (Minnelli’s “The Band Wagon”), a Western (Ford’s “My Darling Clementine”), a silent Buster Keaton comedy (“The General”), a thriller (Hawks’ “The Big Sleep”), and even a big-budget special effects sci-fi extravaganza (Spielberg’s “E.T.”).

How does Wlaschin explain the consistent drop in foreign film viewing among its old bulwark audience: college students? “The people who teach film at USC and UCLA say that their students have no real knowledge of non-American cinema,” he says. “One thing that hurts is the collapse of repertory cinema; you don’t have a Fellini festival where you go and educate yourself about Fellini. Students have never seen a Fellini film.

“In England, subtitled films are shown regularly on all of the TV stations and people don’t mind. A million people will watch a Bulgarian film with subtitles. But here, there are only one or two channels for that: mostly PBS or cable.”

Asked where he thinks the primary non-Hollywood cinematic heat emanates from these days, Wlaschin says, “The odd thing is England--where the industry is virtually dead, where there’s no major company left, and most of the money comes from TV--yet they continue to produce exciting filmmakers and exciting films. Mike Leigh, Stephen Frears, Ken Loach, Peter Greenaway. . . .

“And the other one: the American independents. It’s very exciting now. You saw it in last year’s Top 10 lists: the Carl Franklins, the Quentin Tarantinos and Allison Anderses. Certainly, the Europeans feel this a lot. They pay a lot of attention to what’s happening in the American independent scene.”

Of course, these movies gross less than the huge Hollywood blockbusters. “But you shouldn’t pay obsessive attention to numbers. Take ‘The Marriage of Figaro.’ In its time, after 12 shows, it was taken off, and it wasn’t revived again for 20 years. One of the greatest operas ever written--but it wasn’t liked, at first.”

Opera, film, theater, patrons, audiences, critics, money: It all suggests a complex web, which, year after year, first at London, now in Los Angeles, Wlaschin has has to weave, reweave and then weave again. But he doesn’t seem fatigued. When asked to close with a comment on AFIFEST’s future, he responds, brightly: “Our future is pretty optimistic.”

And, when asked if there’s anything he’d like to do that he’s unable to do now, his reply is instantaneous: “Go to Cannes!”

And see 600 films? A snap.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.