Commentary : ‘TINKER IN TELEVISION’: MANDATORY READING FOR THOSE MAKING A LIVING TINKERING WTIH TELEVISION

As with the rest of the world, the Romper Room known as network television is managed by Do Bees and, more often, Don’t Bees. Grant Tinker is a notable example of the former.

So here’s the buzz on NBC of the early 1980s, when, as its chairman, Tinker led the network back from the brink and made it No. 1:

-- DO BE willing to leave talented people alone to do what you hired them to do.

-- DO BE patient with your programs, nurture them, and leave them on long enough to let the audience come to share your enthusiasm.

-- DO BE concerned about your viewers, as well as your numbers.

Almost a decade after he left NBC, Tinker can’t help getting exercised about the grudge match briefly waged between CBS and his former network as they fired their medical shows against each other on Thursday nights.

“I wouldn’t have done that,” he says. “At least, I hope I wouldn’t. It’s forgetting your first responsibility--to the audience.”

Meeting with a reporter in a midtown Manhattan hotel suite that happens to look out on Tinker’s former workplace, the RCA Building--whoops, make that GE Building--he is talking about his new book, “Tinker in Television: From General Sarnoff to General Electric” (Simon & Schuster), which he co-wrote with former NBC associate Bud Rukeyser.

The book is a revealing memoir of a man who first came to NBC in 1949, when its founder, the legendary General David Sarnoff, “was still in the building--he was up there on the 53rd floor and I was delivering mail on the sixth.”

“Tinker In Television” is also a valuable crash course in the history of the TV business, which Tinker was there to witness and help elevate.

Besides three hitches with NBC, he worked the other side of the street by founding MTM Enterprises, the creative salon that produced some of TV’s most beloved programs, including “Lou Grant,” “The Bob Newhart Show” and, of course, the series that starred his business partner and then-wife, Mary Tyler Moore.

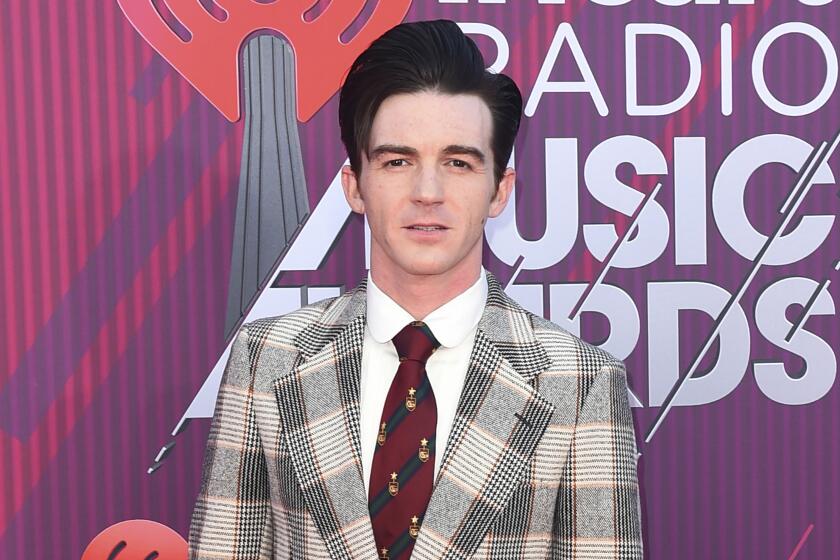

“I just had the good luck to be around people who did the kind of work that the audience appreciates,” says Tinker, who, at 68, is as well-known for his self-deprecating manner as for his lean good looks and California tan. “The success just rubbed off on me.”

In 1981, he brought this low-key approach back to NBC, which, in terms of earnings, ratings, programs and morale, barely had a pulse.

Five years later, when Tinker left to return to independent production, NBC was flush--and, with its parent RCA, about to be bought by G.E. Referring to GE boss Jack Welch, Tinker writes, “I left him an NBC that was the 1927 New York Yankees, and some good advice about how to keep it that way.”

But under the management of Welch and the man he put in Tinker’s old office, Robert Wright, NBC was soon the cellar dweller again and the operative question echoed that of Casey Stengel: “Can’t anyone here play this game?”

Even now, it’s hard to say.

More than inside baseball, the issues Tinker raises in his book make for interesting reading. They also are a balm for viewers fed up with such network antics as schedules that have the stability of a stock-market ticker.

“Our practice was to make a judgment about a show,” Tinker recalls, “and, if we deemed it worthwhile, to really stay with it until it succeeded.” Two shining, oft-cited examples of Tinker’s steadfastness: “Hill Street Blues,” a slow starter in 1981, and, one year later, “Cheers,” a consistent ratings flop--that is, the first of its 11 seasons.

Neither series will soon be forgotten, nor will the Thursday-night time slot each so dependably occupied.

Question: Could most viewers, or even Bob Wright, recall what show occupied most network time slots as recently as last week? Or want to?

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.