Stravinsky That Packs a Punch

Stravinsky’s pre-World War I ballets--”The Firebird,” “Petrushka” and “Le Sacre du Printemps”--not only revolutionized music but later played a critical part in the evolution of modern recording technology. Their rich orchestration and wide dynamic range made them obvious test-pieces for microgroove recording--that is, the long-playing record, which went public in 1948--and then for stereo and its various permutations, including digital and four-channel.

Just as London’s FFRR--Full Frequency Range Recordings--set an industry standard at the dawn of LP, so its FFSS--Full Frequency Stereophonic Sound--was for many listeners the epitome of clarity and depth for stereo in the mid-1950s. In both instances, the designated showpieces were the early Stravinsky ballets, with Ernest Ansermet, the composer’s friend, conducting the ensemble he founded in 1918, the Geneva-based Orchestre de la Suisse Romande.

Now, these recordings are back, in London’s inexpensive “Double Decker” series (443 467, two CDs), and they still pack a hefty punch.

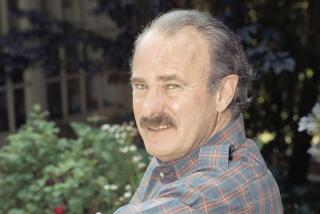

Ansermet (1883-1969) was a ballet conductor when this music was young, and the suppleness of his leadership--bodies in motion, rather than studio-bound instrumentalists are suggested--remains a major attraction in the reissued 1955 “Firebird.” One of the first modern stereo recordings, it has lost none of its sonic impact. But it’s not only recording technique that keeps this performance beguiling. It is the insightful way its every measure is projected by this most intelligent and least self-serving of the master conductors.

Ansermet’s work combines a feel for the shape of the music, for its sensuous curves as well as its incisive rhythms.

It’s difficult to imagine a more seductive “Round of the Princesses” or “Berceuse” than Ansermet’s, while the more dramatic portions have plenty of punch and animation, without showy overemphasis on either quality.

“Petrushka” blazes with wit and color, and with Ansermet there is the added dividend of attention to detail, such as the subtly colored and molded lurchings of “The Moor’s Room,” which in other hands sounds merely like a quirky interlude between the festive scenes.

“Le Sacre du Printemps,” however, uncovers major problems that are only fleeting irritants in the other scores: the playing of the Suisse Romande orchestra, its struggling woodwinds in particular. Ansermet whipped his personnel into a responsive body over the years, but here the hardships imposed by strict Swiss labor laws, which prevented him from importing the first-class players needed to supplement the products of Swiss conservatories, shows.

Still, what Ansermet accomplished was impressive, even in this clarified but hardly small-scale “‘Sacre,” where the notion of dance--rather than of a symphonic blockbuster--is always discernible.

The set is completed with the first stereo recording of the most savagely rhythmical of all Stravinsky’s works, “Les Noces,” scored for pianos, percussion and voices, whose world premiere Ansermet led in 1923. But it doesn’t work here. The use of a vowel-oriented French translation rather than the consonantal original Russian creates an unbridgeable gulf between the instruments and voices.

Stravinsky’s music of the late 1930s and early ’40 didn’t make much impact in the concert hall or on recordings (unsympathetic critics didn’t help) until the early 1960s, when the young and little-known Colin Davis became one of its chief spokesmen. The recordings made under Davis’ direction became to World War II-era Stravinsky what the interpretations of Ansermet and Pierre Monteux were to the early ballets.

Davis’ performances of the terse, harsh Symphony in Three Movements and the cooler Symphony in C--with the London Symphony in its eager, athletic prime--have returned, sounding nattier than ever in a Philips “Duo” bargain package (442 583, two CDs).

The rest of the set is devoted to non-Davis Stravinsky performances, all significant in their time and able to withstand the subsequent competition: the “Symphony of Psalms,” recorded by conductor Igor Markevich with Russian musicians; a laser-like Violin Concerto from the late Arthur Grumiaux and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra under Ernest Bour, and the “Ebony” Concerto and Symphonies of Wind Instruments from the Netherlands Wind Ensemble led by Edo de Waart.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.