the brains behind smart tv : How John Hendricks Is Helping Shape the Future of a More Intelligent World of Television

Last winter, as the air in Washington rang with politicians’ cries to “zero out” government funding for public broadcasting, with some calling for the head of Barney the Dinosaur on a platter, John Hendricks was characteristically quiet. All he did was write a letter.

It would have been understandable if Hendricks, who runs cable TV’s Discovery Channel and The Learning Channel, had joined the public television lynch mob--if only to watch and gloat. After all, Hendricks, perhaps even more than House Speaker Newt Gingrich is nudging PBS--ever so gently--toward the precipice. By bringing PBS-style documentaries to cable television, Hendricks has helped to create an alternative for high-minded TV viewers and corporate sponsors, draining some of the lifeblood from PBS and making it more vulnerable than ever to its longtime critics.

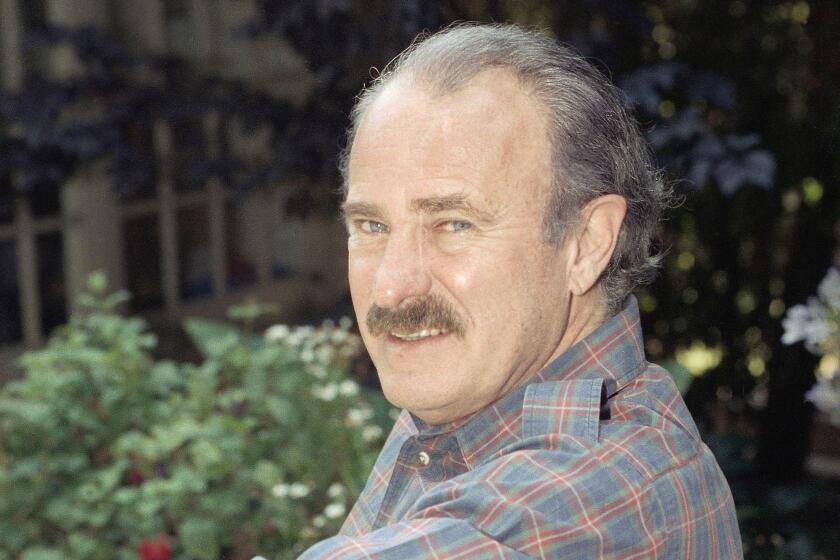

Still, Hendricks, 43, wasn’t about to join the crowd that was kicking PBS last December. For one thing, the soft-spoken, Southern-born entrepreneur is too polite. For another, he’s too smart. Hendricks instead sent a cordial note to PBS President Ervin S. Duggan, suggesting the following: Discovery would help pay production costs for top PBS shows such as “NOVA” and “Nature” if PBS would allow Discovery to show the programs first (with subsequent airings on PBS). It was a perfect solution for all, by Hendricks’ reckoning: PBS would save money, Discovery would have a couple of hot shows to sell to its advertisers, and no viewer--wired for cable or not--would lose out. That’s one way of looking at it; one might also surmise that in such a deal, PBS would lose an important piece of its established franchise, while Hendricks’ upstart Discovery Communications would just keep getting stronger.

To date, Duggan hasn’t responded to the letter, but Hendricks thinks it may be just a matter of time before PBS is compelled to seek out such partnerships. And he insists that if it joins him, the experience will be painless. “I like PBS,” he says, smiling beneath his thick mustache. “I don’t want to see anything bad happen to them.”

In the genteel business world of John Hendricks, it seems, everybody wins; it’s just that Hendricks wins more. During the past decade, Hendricks has created and shown more educational documentaries than anyone else in commercial television. And he has been rewarded with a company that has $2 billion in revenues and is poised to become an international multimedia empire.

The Discovery Channel reaches 64 million homes, about two-thirds of television households in the United States, and Hendricks has begun piping the channel into Europe, Asia and Latin America. He has already created four additional cable channels--dedicated to nature, science, history and lifestyle documentaries--that will show up on some cable systems in coming months. Last month, he acquired a chain of stores that he will convert to Discovery retail outlets, selling nature and science videotapes and CD-ROM discs. And next year, Discovery will venture into movie theaters with big-screen nature films that, Hendricks hopes, may snatch some of the “Lion King” family-movie crowd from the clutches of Disney.

As his empire grows, PBS seems destined to keep shrinking, which means Hendricks could emerge as the leading proponent of “smart TV.” Walter Cronkite, the former network news anchor who now produces documentaries for Discovery, says of Hendricks: “He’ll be at the forefront of enlightened television for years to come.”

But will that be a good thing? Critics say that Hendricks’ programming steers clear of anything that might displease advertisers. Though it’s hard not to admire Hendricks--a squeaky-clean Alabamian who might be the only commercial TV programmer in America to have gotten rich by not underestimating the intelligence of his audience--some wonder whether he can reconcile the conflicting interests of commercialism and educational TV.

“What Discovery has tried to do runs parallel to public TV, but the question remains as to whether they, or any cable network, will take the leaps into daring programming,” says longtime PBS producer and news anchor Robert MacNeil. “Will they be willing to do something just because it’s a worthwhile idea, without being overly mindful of ratings and commercial concerns? The jury is still out.”

If Hendricks is the future of smart TV, viewers should prepare to receive a practical education because his company will never be mistaken for a benevolent public broadcasting bureaucracy. On the contrary, it is a model of marketing-driven, bottom-line pragmatism. At Discovery, enlightenment is good; but enlightenment that pulls ratings, helps sell luxury cars and can be spun off onto CD-ROM discs is even better.

*

Public television, Washington Post television critic Tom Shales once observed, tends to be dominated by “insects mating or British people talking.” John Hendricks, a young entrepreneur in search of a big idea back in the early 1980s, noticed something more: The bugs were more popular than the Brits.

An outsider who knew nothing about the TV business, Hendricks had studied PBS ratings history and saw that public television’s top-rated programs were nature and science documentaries--not the imported British parlor dramas or the controversial public-affairs programs that tended to anger Republicans. And so, in launching Discovery, he opted to take the insects and animals, and leave the rest.

Today, the Discovery Channel’s most reliable performer is the shark, star of the network’s annual, high-rated “Shark Week” marathons. Almost as popular are the lions, tigers and bears that roam through the weekly series “Fangs!” When not baring teeth, Discovery sometimes draws big ratings (which are small compared to the networks’) in a subject area that Hendricks refers to as “boy toys”--airplanes, space rockets and large ships. In March, Discovery set its own all-time ratings record with “Carrier: Fortress at Sea,” a documentary that spent two hours roaming the nooks and crannies of an immense aircraft vessel.

Such programming has led some to believe that Hendricks’ brand of TV is not just smart--it is also crafty. “Discovery tends to stay within the sphere of programming that is popular and safe,” says Paula Apsell, executive producer of PBS’ NOVA. “Anyone in this business knows that if you make a show about sharks or big ships, it’s going to be popular.”

But Discovery’s programming is not so easily categorized. With prime-time programs that, for example, probe the significance of bat dung, Hendricks has sometimes tested the attention span of viewers in ways that even PBS might not dare. In recent months, the channel produced and ran “The Promised Land,” a documentary series about the migration of African Americans from the South to northern cities. Another program, “Nightmare’s End,” featured seldom-seen film footage of the liberation of the Nazi camps, while “The Fall of Saigon” may have been the most exhaustive treatment to date on the denouement of the Vietnam War.

On Discovery’s sister network, The Learning Channel--which has a slightly more educational bent than the adventure-oriented Discovery--Hendricks drew a post-Super Bowl viewing audience this year with a science special on human reproduction and got TLC’s best ratings ever. And Hendricks’ “Great Books” series has already brought to the screen a number of tomes that were not exactly made-for-TV material, including Charles Darwin’s “Origin of the Species.”

On the cable dial, where sports, music videos and movies rule, Hendricks’ two docu-channels are a couple of quiet oases. “You feel like you’re entering a time warp when you turn on Discovery,” says critic Shales, referring to slow-paced documentaries that look as if they might have been shot anytime in the past 30 years. This quality seems to particularly appeal to older viewers; Discovery tends to attract viewers over 40 years of age. And yet, despite the decided lack of trendiness, the channel has become something of a hot item. Hendricks receives fan letters and calls from the likes of Hugh Hefner, Mick Jagger and Marlon Brando, while movie-star-of-the-moment Brad Pitt rhapsodized on the wonders of Discovery in a recent magazine profile. Hendricks is appreciative, but confides: “I think some people probably like to say they watch Discovery more than they actually watch it.”

*

Hendricks, on the other hand, would be a bona fide watcher of the Discovery Channel even if he didn’t own it. He has been fascinated with the notion of exploration since his boyhood in Huntsville, Ala., where he grew up in the shadow of the NASA space center that developed the Saturn rockets that took man to the moon. “I could hear the engines when they tested Saturn 5,” he says. “I could actually feel the rumble of those rockets when I was in my house.”

Hendricks was the type of kid who built his own telescope and who preferred watching science, nature and history documentaries to “Bonanza.” After studying history and astronomy in college, he ended up working in academia, as a fund-raiser for a couple of universities. His love of documentaries stayed with him, and as the cable TV industry burgeoned in the early 1980s, “I noticed that no one was doing a documentary channel,” he says. “And I became obsessed with this idea.”

It was not a popular one at the time. The broadcast TV networks had largely abandoned documentaries by the late 1970s, canceling hourlong news or science series such as Walter Cronkite’s “Universe.” “The problem with TV documentaries was never one of low ratings,” says Cronkite today; he notes that his show garnered strong ratings, but attracted the sort of viewers who simply would not stay tuned for the sitcoms or detective shows that followed. For that reason, Hendricks believes, “the networks decided to give up on thoughtful TV and go entirely with entertainment TV. But when that happened, a lot of people--perhaps a third of the country--were left feeling neglected by television. Aside from PBS, they had nowhere to turn for intelligent programming.”

In 1982, Hendricks rushed into that void with a plan to launch his network using recycled documentaries from overseas and from PBS. But in the midst of those gold-rush days of cable, Hendricks had trouble finding backers. Even Disney, a company that should have understood the potential of lions and elephants, walked away from an invitation to take a $6-million ownership stake (that investment today would be worth about $800 million, Hendricks doesn’t mind pointing out).

In need of credibility, he sought the authoritative voice of Cronkite, to whom Hendricks wrote. When they met, Hendricks’ quiet charisma--honed in his years of university fund-raising--immediately won over the journalist. “I was impressed by his total belief in this idea,” Cronkite says. So he provided Hendricks with a signed letter extolling the virtues and viability of documentary TV, which Hendricks then waved in front of wary investors.

By mid-1985, Discovery had enough money to go on the air, showing secondhand nature programs. Then, six months into his first season, Hendricks hit the wall. A major potential investor pulled out, and Hendricks found himself unable to meet his payroll. “I figured it was over,” he says. But in the 11th hour, Hendricks was bailed out by John C. Malone, chairman of Tele-Communications Inc., America’s largest cable distributor, who, along with three other cable companies, decided to take a majority stake in Discovery.

“I liked the idea of a documentary channel because I watch documentaries myself,” says Malone. But Malone, a dominant and controlling figure who presides over much of the entire cable business, had other reasons to form a partnership with Hendricks. With the cable industry facing regulatory attempts to restrict its rates, Hendricks, an erudite fellow with an easy smile and a slate of educational programs, would prove to be a good ambassador, one who could provide respectability for an industry previously dedicated to serving up pay-per-view films and prizefights.

“Malone and the cable industry began to trot Hendricks out as the good guy of cable,” says Richard Katz, who covers the cable business for Multichannel News. “He became the man in the white hat.”

Hendricks got plenty out of the partnership, too. In addition to pumping in the funds to keep Discovery alive, Hendricks’ partners had access to half the cable boxes in America. By 1990, the Discovery Channel was the fastest-growing cable channel, reaching 50 million homes. Then, as Hendricks sought to expand his operation in 1991 by acquiring The Learning Channel, Malone once again seemed to be instrumental.

At the time, Hendricks found himself competing with Lifetime Television, which signed a letter of intent to purchase The Learning Channel for $39 million. Malone then reportedly advised his cable outlets around the country to remove The Learning Channel from their lineups. (Malone says he simply stated that TLC “should not count on our continued distribution.”) Lifetime subsequently pulled out of the deal and Hendricks claimed TLC for a lower price of $32 million. A suit filed later by the original owner of The Learning Channel, charging TCI and Discovery with “anti-competitive use of monopoly power,” was eventually dismissed. But it was clear to observers that the amiable Hendricks was now playing in the rough, tough big leagues. Says Katz: “There are some who might say that Hendricks is propped up by the evil empire of TCI.”

*

The alliance hasn’t tarnished Hendricks’ pristine image much. “He has no enemies, which is very unusual in the television business,” says Jon Mandel, a senior vice president at Grey Advertising, a top Madison Avenue agency. Even Hendricks’ competitors are admirers. Nickolas Davatzes, president and CEO of A&E; Television Network, says: “Perhaps because he worked in an academic environment, there’s something professorial about him--and that’s refreshing in this business, where you have so many accountants, lawyers and production people running things.”

At times, Hendricks can seem almost too good to be true. He actually uses the word “gosh” in conversation. He never misses his 13-year-old daughter’s or his 10-year-old son’s soccer games. He is a paternalistic boss who recently created a company photo yearbook because, says Sandy McGovern, a former employee, “he was embarrassed when he’d be in the elevator with someone and he didn’t know their name.”

Ensconced in Bethesda, Md., Hendricks remains “an outsider in the TV business,” says Advertising Age media editor Joe Mandese. He doesn’t spend much time in Los Angeles or New York if he can help it. He has no particular ties to the local politicians of either party (“I try to stay independent,” he says). His few celebrity friends seem to be cut from the same wholesome cloth as Hendricks himself: Olympic hero Bruce Jenner, astronaut Buzz Aldrin, children’s TV actress/producer Shelley Duvall. Duvall bubbles over when asked about Hendricks, saying, “He’s like the Walt Disney of educational television.”

There is no reason to doubt that Hendricks’ nice-guy image is authentic, though a cynic might point out that in his case, it certainly pays to be good. His white hat and earnest manner have served him well as he has occasionally lobbied for higher cable rates and for access to more homes. And his educational, thoughtful programming makes him a popular fellow on Madison Avenue these days. That alone may be one of Hendricks’ more significant accomplishments: He seems to have demonstrated that it is possible for advertising and sophisticated television to coexist. “One needn’t drive away the other,” Hendricks insists.

Considering the state of commercial TV just a few years ago, when sponsors seemed to gravitate toward the banal, Hendricks’ success with advertisers may represent a significant shift in the commercial sensibility. It also suggests that one of the guiding principles of public TV--the belief that commercialism automatically leads to a “dumbing down” of programming--may be out of touch with the realities of television in the 1990s.

When public television was created more than a quarter-century ago, the broadcast TV networks favored a mass-appeal programming approach, geared to pleasing advertisers “who simply wanted to reach the most bodies at any given time,” says Don Schultz, professor of integrated marketing communications at Northwestern University.

Meanwhile, public TV, free of commercials, aired programs that were more “niche” oriented, targeted to opera lovers, history buffs and others with refined tastes. Many of the people at PBS believe that this dichotomy still exists today. “You have to have public TV,” insists PBS’ star documentarian, Ken Burns, “because commercial television automatically gets pulled toward higher ratings. The commercial marketplace will, for the most part, tend toward the safer ‘Gilligan’s Island.’ ”

But others note that Gilligan is long gone. “Television across the dial has gotten smarter in recent years,” says Betsy Frank of Zenith Media Services Inc., noting that on almost any given night one can find an “NYPD Blue” or other top quality program. Even sitcoms, a la “Seinfeld,” are increasingly geared to more sophisticated viewers. Part of the driving force has been advertising, which is more targeted and demographics-conscious than in the past. “Advertisers are no longer concerned just with how many are watching,” Schultz says, “it’s now more a matter of who’s watching.”

Automotive companies, the single largest advertising category, are particularly hungry for a “quality male” demographic. “Over the years,” says Frank, “the auto companies found that the educated male was spending less time with traditional TV. Smart guys just weren’t watching sitcoms.”

Hence, the car marketers were realizing much the same thing Hendricks was--that a segment of the population was being shut out by commercial primetime TV. Some of those people were watching PBS, but PBS would not sell commercials to advertisers, forcing them to settle for paid “mentions” of an underwriter company’s name at the start of a program. And so when Hendricks arrived, offering the same kind of audience as PBS--educated, higher-income, with light viewing habits--with none of the commercial restrictions, advertisers welcomed him. And since his sharks and “boy toys” particularly drew male viewers, the car companies, financial companies and computer makers flocked to Discovery. “Hendricks’ two channels took some of the PBS franchise, and indirectly they’re one of the reasons for the demise of PBS,” says Mandese of Advertising Age.

Because he has captured the elusive “light viewer,” Hendricks can charge advertisers a premium--in industry parlance, a high CPM (cost-per-thousand). “Hendricks has done a magnificent job of selling the image of smart television,” says Grey’s Mandel. “He has created an aura around the channel. The thinking is, who else but an educated person would sit still for these programs? We’re talking about a channel that does a special all about bat s- - - and somehow gets good ratings with it.”

*

Attracting desirable viewers is only one part of the business equation at Discovery. The company is also a leveraging monster. One might not suspect that a documentary, seemingly the least commercial form of filmmaking, could be marketed as if it were a widget. In fact, the documentary is the perfect widget--which, again, is something Hendricks understood at the outset.

A documentary can be recycled endlessly--”A program about an elephant is timeless, it’s an evergreen,” Mandel says--and is usually relatively inexpensive to produce; the on-camera talent literally works for peanuts, and, as one Discovery producer points out, “the big cats don’t get residuals.”

In addition, the demand for documentaries is almost unlimited. They can be sold to libraries and schools, which Discovery does. They can be spun off into other media; last year, Hendricks created a multimedia division that now takes Discovery jungle treks and converts them into CD-ROM programs that retail for $50. Finally, the programs can be resold--with a little dubbing of the voice-over--nearly anywhere in the world. “Nature and science documentaries are one of the few programs that can run in almost any country,” Hendricks says, “because there’s no cultural or political bias to these programs.”

This elaborate process of selling smart TV is achieved via a well-oiled machine that Hendricks has assembled in Bethesda. Discovery’s staff of about 600 includes an army of enthusiastic young executives, who tend to race from meeting to meeting, occasionally toting cellular phones, and often speaking a language of brand-marketing buzzwords.

On a recent morning, Discovery President Greg Moyer, who wears Gordon Gekko-style suspenders, announced to a visitor: “Now the game is to expand our brand off TV, to become a global brand in a multitude of media.” Bill Goodwyn, who heads up distribution, was in a nearby office, sketching diagrams and saying: “Once you’ve got the distribution, you can sell your ancillary products--CD-ROM, videos, whatever.” Later, Goodwyn explains: “There are viewers who just want to see animals, nothing else, and by having niche channels, we can make sure that that particular product is available to those people at all times.”

To get the “product” just right, Discovery programming is largely designed from within--unlike PBS programs, which are usually conceived by independent filmmakers and local TV station producers. At Discovery, a small brain trust headed by Hendricks and top programmer Clark Bunting decides what to air based on three prerequisites: “It has to adhere to our quality mission, we must be able to sell it to the advertising community, and it must get ratings,” Bunting says.

The concern among outsiders is that advertisers and ratings might take precedence. “I don’t think you’ll ever see Discovery take the kind of risks PBS would,” Shales says. “Because they’re advertiser-supported, they tend to be apolitical, and they shy away from anything that might breed controversy.” For example, Shales notes, when TLC ran its popular documentary on human reproduction, co-produced with British television, it cut out incidental nudity that was in the original version of the documentary. “That’s the kind of wimpy thing you do when you’re worried about advertisers,” Shales says.

Asked about the influence of advertisers, Hendricks looks puzzled. “I really can’t think of any instance in which advertisers have told us not to do something,” he says. He acknowledges, when pressed, that Chrysler had direct input into the creation of a program that the car-maker sponsored. This fall, a new how-to home improvement series on Discovery will be produced by the retailer Home Depot, which suggests “infomercial” possibilities. And the recent “Carrier” documentary starring a naval ship was sponsored, in part, by the U.S. Navy (though the Navy pulled its ads after seeing the finished film, in which a seaman, in one scene, complains about having to clean the toilets).

But the problem that critics have with Discovery is not that the channel is slanted toward sponsors; on the contrary, they say, there is simply no slant at all. “Part of the reason advertisers like Discovery is they know they won’t have to deal with controversy--it’s a safe, quality environment,” Mandel says. “Don’t look for Discovery to do anything edgy.”

On the other hand, the same is being said of PBS these days. In the past two years, public TV has been repeatedly accused of shying away from controversial programs. “For the last several years, it’s been difficult to produce social-issues films for PBS,” says documentarian Steve Fischler, whose Pacific Street Films has worked with PBS. “PBS tends to be nervous--understandably--about doing anything political these days.”

Fischler also points out that PBS has become increasingly dependent on corporate underwriting in recent years. “And the fact is, corporations don’t support social or political films,” he says. “So what we’re seeing is that both public TV and cable are reluctant to tackle anything difficult, and it will probably continue in that direction.”

Hendricks is aware of the criticism that his channels don’t take risks. “It tends to be jarring to our viewers to go from a quiet nature documentary to a social-issue program,” he explains. He says he would prefer to handle tougher subjects on a separate channel. “I could see us developing a channel that focuses on issue documentaries, in the tradition of Edward R. Murrow,” he says. Would advertisers support it? “They won’t have to,” he says. “The viewers will pay for it. The viewers will have more control in the future of television.”

*

The future, as Hendricks envisions it, holds limitless opportunities, which will be ushered in by the miracle of digital technology. As the video signal fed into homes is expanded in coming years, there will be room for more channels, more viewer options. Some might see this as a growth of TV clutter, or--since the new viewing options will likely be paid for by viewers--a further commercialization of television.

But Hendricks contends that the new era will bring a greater democratization of TV. When the broadcast networks ruled, says Hendricks, “the country was held hostage by the viewing habits of the majority.” Cable changed that by providing more alternatives. The next wave will further explode the number of options available to viewers.

Talk of TV’s future has grown tiresome of late, with much speculation and hype emanating from cable companies, telephone companies and consortiums; amid the prognostications about coming miracles, hard facts and proven results have been scarce. Hendricks, though, is one of the few who has gone beyond talking. He has already created a first-generation interactive TV platform.

That Hendricks managed to invent something like Your Choice TV in his spare time (it’s separate from his Discovery operation) says something about both his energy level and his common sense. Hendricks observed that while the delivery of expanded TV signals into homes is imminent (beginning next year), expanded programming is nonexistent. So he created an interactive system based on existing television programs.

The idea behind Your Choice TV is simple: The viewer scrolls through a listing of some of the best TV programs that have run during the past week, then chooses one; for 79 cents (rates vary), you get to see the episode of “Saturday Night Live” that you missed a few days earlier. Yes, you could have videotaped the show and saved the 79 cents, but Hendricks is betting that you forgot, or couldn’t be bothered.

Your Choice TV is available to viewers in a few test markets around the country, and most of the major broadcasting and cable TV networks have signed on, providing access to their shows. So far, it’s testing well with viewers, despite a couple of limitations on the system. It’s not an instant video-on-demand system; you have to wait until a start-time on the hour or half-hour to watch the selected program. And right now, the system doesn’t include “Seinfeld” or many of the other network shows owned by Hollywood studios, which have opted not to release their shows to Your Choice.

Still, Hendricks’ achievement is impressive, says Advertising Age’s Mandese. “He’s been able to coalesce an entire industry behind this system,” he says. “With all the talk about interactive TV, this is the only thing that’s producing measurable results right now. Hendricks is perceived as someone who’s leading the way into the next level of TV.”

Whether Your Choice TV will eventually become an industry standard is uncertain. Nevertheless, Hendricks should flourish in the multi-channel, interactive TV world for a more fundamental reason: “As TV becomes more crowded, with more choices to be made, brand recognition becomes important in attracting viewers,” says Hendricks. And Discovery is, surprisingly, one of the strongest brands in all of television; a recent Equitrend quality survey among the general public found Discovery to be the most admired name on TV, ranking ahead of the other cable channels, the broadcast networks--even ahead of PBS, which ran close behind.

With PBS in trouble, Discovery stands to inherit even more of the “quality viewer” market--though Hendricks insists that he would rather see PBS survive “because they help promote quality television, and that can only help us.” That’s part of the reason Hendricks wants to “help” it with co-productions. But would a partnership with Discovery really help PBS? PBS’ Duggan (who declined to be interviewed for this story) has said that he is concerned that cable companies might wish to “pick apart” its lineup.

“The idea of occasional co-productions with Discovery is fine,” “NOVA’s” Apsell says, “but I’m not sure it would be appropriate to allow a commercial company to reap the benefits of the “NOVA” brand name, considering all that taxpayers have invested in that brand.” She also worries about editorial control. “Could we do less attractive subjects? Or would they tell us which subjects were appropriate?”

Regarding the issue of control, Hendricks says simply: “If we provide the majority of funding, then we would have editorial control.”

While the co-venture would provide some financial relief for PBS, A&E;’s Davatzes says, “It would be just a Band-Aid for PBS--it won’t solve their real problems.” Indeed, it might create new ones, perhaps by luring the companies that underwrite “NOVA” and “Nature” away from PBS to Discovery.

For now, Hendricks will let PBS sort through such concerns; he’s made the invitation, and it’s not his manner to push things. Besides, he has other concerns to focus on, including his newest venture, Discovery Pictures (the unit’s first theatrical film, “The Leopard Son,” will be released early next year), and his burgeoning retail chain. Hendricks has 11 stores now, but hopes to open as many as 300, perhaps featuring in-store virtual reality displays that will allow visitors to wander into the wilds of the Serengeti without ever leaving Cleveland.

Do we really need this much Discovery in our lives? It’s possible Hendricks may be overreaching. “Discovery is trying to do a lot of things simultaneously,” Davatzes says, adding, “It’s not an approach that we would take.”

But Hendricks isn’t worried. He may have watched too many exploration documentaries, but he seems to have no fear of venturing into the unknown. In fact, lately he has talked with NASA officials about the possibility of putting Discovery cameras on a lunar expedition. That seems appropriate: Thirty years after listening to the roar of the moon rockets in his childhood home in Alabama, Hendricks may finally get to climb aboard.

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.