Hallucinations and Spellbound Reality : HALLUCINATING FOUCAULT by Patricia Duncker; The Ecco Press $19, 192 pages

First novels are often fraught with agonized self-exploration, predictable plots or histrionic, cartoonish characters. They tend not to soar above daily life but flounder in it. The author runs the risk of doing what all young parents are fruitlessly warned against: growing up alongside their children.

Here is an unusual first novel, an imaginative leap into the mind of a dedicated reader--referred to throughout simply as “the reader”--who is writing his thesis at Cambridge on the writer Paul Michel, bad boy novelist of French letters, creator of five novels and one collection of stories between 1968 and 1983. “He was the wild boy of his generation,” says the student, noting the influence of the philosopher Michel Foucault on Michel’s work. Both were “captivated by the grotesque, the bizarre, the demonic.” But while Foucault’s narratives are “huge, dense, Baroque,” Michel “wrote with the clarity and simplicity of a writer who lived in a world of precise weights and absolute colors.” Foucault “was the idealist. Paul Michel was the cynic.”

Our reader is minding his own business, drawing neat parallels between Foucault and Michel in the university library when he falls under the spell of an intense Germanist, studying Schiller in the Rare Books Room. “Look,” she says when they speak for the first time. “I live in a two-room flat, so you can’t move in. But I’d like to go to bed with you. So why don’t you come round tonight.” He does just that. “She was like a military zone,” he thinks. “Some of it mined.”

The Germanist (not a soft and fuzzy Muse, but a Muse nonetheless), of course, knows more about Michel than the reader, including the fact that “He’s in the madhouse. Sainte-Anne in Paris. He’s been there nine years. They’re killing him with their drugs, day after day.”

She is disgusted by the fact that this student of Michel’s writing has so utterly neglected love in his relationship to his object of study that he has failed to learn of Michel’s whereabouts. She as much as dares him to go find Michel and rescue him from the asylum.

“She was the huge swell beneath me, the extraordinary energy itself, for all my undertakings.” She messes up his neat thesis. Michel, she says, “fell in love with Foucault. It is absolutely essential to fall in love with your Muse. For most writers the beloved reader and the Muse are the same person. They should be.”

He goes to Paris (passive researcher turned knight errant) to find Michel. When asked by the hospital’s administration about his relationship to the patient, he says, “I’m his reader. . . . And even if he doesn’t write anymore I am still his reader.”

He does gain access, he does spend many hours with Michel, and he is able to negotiate a leave of two months for the patient. In the course of their conversations, he emerges now and then from the veil of charm surrounding his author to ask some real questions about, for example, “the chill in that beauty [of Michel’s writing], that cynicism, that detachment. A terrifying indifference.” Michel answers that “Maybe the remoteness of my texts is the measure of my personal involvement? Maybe that chill you describe is a necessary illusion?” The reader discovers in Michel “a grandeur, a simplicity of spirit that was incapable of lies. . . .”

They spend many happy hours in the sun of the Midi. And then it ends when the author, finally, escapes.

Which is more than we can say for our reader, who is haunted for the rest of his life, as much as he tries to stick strictly to the texts, by the author and his Muse.

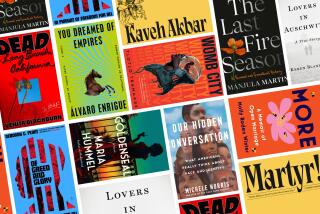

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.