Swiss Filmmakers Find Gold

The UCLA Film Archive’s “Switzerland and World War II,” a series of eight films screening tonight, Saturday and Sunday at James Bridges Theater in Melnitz Hall, could scarcely be more timely, considering the current scrutiny of the supposedly neutral country’s relationship with the Third Reich.

Actually, even before World War II was over, Swiss filmmakers were delving into their country’s not-so-covert support of Hitler and its anti-Semitic policies. It’s a smart move on the part of Pro Helvetia, the arts council of Switzerland, to have assembled this series showing that Swiss filmmakers have for a long time tackled what their government has evaded.

Thomas Koerfer’s “Embers” (1983) launches the series tonight at 7:30 p.m. with a compelling drama starring Armin Mueller-Stahl as a Swiss armaments manufacturer supplying the Third Reich. He and his wife (Katharina Thalbach) and small son (Thomas Lucking) live in a 19th century castle worthy of royalty. It is the perfect setting for the tragedy that occurs inevitably and which lays bare the plight of Polish refugees. “Embers” is neither as stylish nor as decadent as Luchino Visconti’s “The Damned,” inspired by the German industrialist family the Krupps, but is highly effective as a traditional narrative. Also featuredis the dazzling Polish actress Krystyna Janda.

You can believe that Alfred Hitchcock could have exclaimed, as reported, of “The Last Chance,” “Talk about suspense! This has it!” Actually, the 1945 film, which screens following “Embers,” has remarkable parallels to 1991’s best foreign-language film Oscar-winner, “Journey of Hope,” in that it deals with a group of refugees struggling to get to the Swiss border in the midst of a snowstorm--and offers a wryly critical commentary on Swiss hospitality.

The film opens in the final treacherous days of World War II in Northern Italy, where two Allied soldiers--one British (E.G. Morrison) and one American (Ray Reagan)--who have escaped from a prison camp are trying to make their way to Switzerland, and eventually risk their lives to help a group of refugees of assorted nationalities.

There is a bit of heavy-handed propaganda for brotherhood, but on the whole, the beautifully photographed black-and-white film is still remarkably suspenseful and poignant. The wonderful character actress Theresa Giehse plays a stalwart Jewish refugee; today, she is best remembered for her final film appearance as a bizarre old woman in Louis Malle’s surreal 1977 “Black Moon.”

Erich Schmid’s 1995 “He Called Himself Surava” (Saturday at 7:30 p.m.) is a thoroughly engrossing documentary about the amazing and harrowing life of journalist Peter Hirsch, which shows how freedom of the press can never be taken for granted.

Looking back on his life, Hirsch tells us that in 1940, at the age of 28, he became editor of the weekly Die Nation, which throughout the war maintained an anti-Nazi stance. But as circulation rose from 8,000 to 120,000, the paper won the enmity of the Swiss government, which censored it so heavily that by the beginning of 1945 Hirsch, who had taken the pen name of Surava (after an Alpine village), finally resigned. But that was just the beginning of his persecution--and of 45 years of working under a series of aliases--that lasted until 1991.

In the 1980 Oscar-nominated “The Boat Is Full” (Sunday at 7 p.m.), Swiss writer-director Markus Imhoof demolishes the widespread assumption that if refugees from Hitler’s Germany were lucky enough to reach the border of neutral Switzerland they were home safe. In the process, he has made a most harrowing film. Imhoof, whose background is in documentaries, wisely trusts in the overpowering quality of his material and tells his story as simply and directly as possible.

What actually happened was that by the summer of 1942 the Swiss government declared “the boat is full,” having accepted 8,300 refugees, most of whom were only passing through to other countries, primarily the United States. Nevertheless, emigration policies were established that were so stringent as to all but close the Swiss border--especially to Jews. No longer could a Jew request sanctuary as a political refugee.

We first see some Swiss soldiers bricking up a railroad tunnel, cracking anti-Semitic jokes as they work. Then we’re thoroughly dislocated as a train comes to an abrupt halt and people start scrambling from their hiding places on board, trying to flee some soldiers, apparently German. The next thing we know, a sturdy Swiss woman (Renate Steiger) opens her barn door and comes face to face with six bedraggled people.

Imhoof, whose ensemble cast--headed by Tina Engel and Curt Bois--is in every way remarkable, takes pains to clarify that not all his fellow countrymen are prejudiced. He suggests that the air in 1942 was thick with a virulent anti-Semitism.

Especially hateful is the local cop (Michael Gempart), whose evil is rooted in an abysmal ignorance. It’s the old story--if you can regard those different from yourself as something less than human, you can eventually justify any treatment of them whatsoever.

*

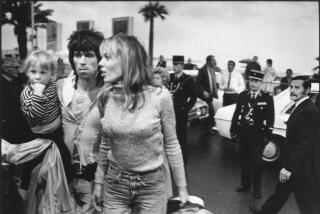

The American Cinematheque’s “Fast Forward: Recent French Filmmaking, 1986-1998” continues Friday at 7:15 p.m. at Raleigh Studios’ Chaplin Theater with Philippe Garrel’s “I Don’t Hear the Guitar Anymore” (1990), followed by Olivier Assayas’ 1986 “Desordre,” unavailable for preview, and his “Winter’s Child” (1989).

No one takes l’amour more seriously than the French, and “Guitar” and “Winter’s Child” avoid humor at all costs. Garrel focuses on some marginal types relentlessly but gradually draws you into the transient relationship between a beautiful woman (Johanna ter Steege) and a pensive man (the late Benoit Regent) as they drift into drug addiction and beyond that to separation, survival and a problematic reunion.

Whereas “Guitar” grows steadily in power, “Winter’s Child” grows glum, an instance of a director with a compelling style unable to make his people compelling. It’s a study of obsession, centering on a talented young set designer (Clotilde de Bayser) consumed with love for an actor (Jean-Philippe Ecoffey) with whom she has had a run-of-the-play romance he regards only as casual. Meanwhile, a young architect (Michel Feller) hastily rejects his pregnant lover (Marie Matheron) only to regret it the rest of the film; meanwhile, Bayser and Feller futilely try to console each other.

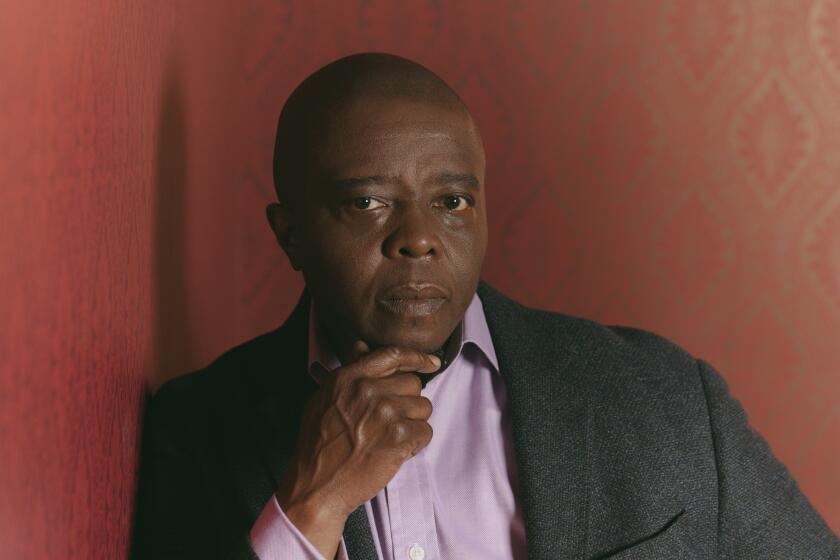

A complex and truly original film, Arnaud Desplechin’s 1991 “La Sentinelle” (Saturday at 9:30 p.m.) on the surface is the story of a young medical student (Emmanuel Salinger) adjusting to life in Paris after spending years in Germany as the son of a diplomat.

At the outset, however, two tremendously jarring incidents--Salinger’s exceptionally harrowing interrogation by a seemingly deranged border patrolman and his discovery of a mummified head in his luggage--let us know that we’re in for more. For all its Hitchcockian twists, “La Sentinelle” is a lot closer to Jacques Rivette’s “Paris Belongs to Us”; the Cold War may be over, but its paranoia lingers on dangerously. Information: (213) 466-FILM.

*

Saturday and Sunday at noon at the Nuart, Filmforum presents Michael Bockner’s tedious, arch “Johnny Shortwaves,” dealing with a resistance movement set in an oppressive future. It’s said to have been inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s “Alphaville.” You’re better off renting a tape of the Godard classic. Information: (310) 478-6379.

*

LACMA’S “Chaplin: A Life on Film” retrospective continues Friday at 7:30 p.m. in Bing Theater with a program of shorts followed by Peter Jones’ new documentary, “Charles Chaplin: A Tramp’s Life.” Screening Saturday at 7:30 p.m. is another program of shorts followed by “The Gold Rush” (1925). Information: (213) 857-6010.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.