When No Green Card Means No College

It is law that leaves students suicidal, disbelieving, or quietly hopeless. It leaves high school teachers enraged and weeping, and drives a few to risk their careers, and even become accomplices to fraud.

But to its advocates, it is fair and necessary that federal law and court decisions have effectively barred most undocumented students from going to college.

Even defenders of the policy acknowledge that it has created one of the most wrenching and painful immigration conundrums facing the state, particularly in Los Angeles’ poorest urban high schools.

And in a confounding twist, some of the students barred from college are high achievers, even valedictorians.

Most large central Los Angeles-area schools, such as Franklin, Belmont, Garfield and Roosevelt, seem to have significant numbers of seniors who are illegal immigrants. At some point, usually late in their high school careers and often after winning acceptance to prestigious schools, students there and throughout California come to realize that the door to higher education is closed.

“I’ve had kids break down in my office,” said Antonio Reveles, a counselor at Bell High School. “I’ve had to sit with them for hours.”

Court rulings require states to offer public education to all children, regardless of their immigration status. But the legal right to attend school as other California residents do ends after 12th grade.

Undocumented students can apply, and be accepted, at California universities, but they are barred from receiving in-state tuition discounts or financial aid for college--the result of years of political and legal battles.

They must pay full out-of-state tuition, just like international students, even at community colleges. Students are asked their citizenship status, under penalty of perjury, to determine tuition costs. If they are not citizens, they must show evidence that they can legally establish a domicile here--usually by showing proof that they have permanent residency status.

Immigrants who lie jeopardize their chances of ever becoming legal residents, immigrant advocates say.

Those who can’t meet the requirements must pay out-of-state rather than in-state tuition. In the UC system, for example, the difference is $14,043 a year versus $3,429. Even at a community college, the costs are far higher--$3,900 versus $330.

Immigrant advocates have long fought the tuition rules, arguing that kids shouldn’t be punished because their parents brought them to the U.S. illegally.

Such children speak English, and have little connection with their homeland, they argue. Why shouldn’t the state benefit from their contributions as college-educated adults?

Mexican President Vicente Fox added his voice to the debate this week as he toured California, urging the United States to remove the barriers blocking illegal immigrants from attending college.

But defenders of the policy say a basic issue of fairness is at stake.

“Why should an illegal alien be given more rights than a person who’s grown up in Arizona and whose parents have paid taxes all their lives?” asked Richard Knickerbocker, a Santa Monica attorney involved in the court cases.

The right to pay resident tuition in California is often sought by citizens and legal residents, and not always granted. For example, the frequent moves of military families can make it difficult to establish residency in a state. The aim of the federal law is to ensure that such people aren’t being denied a benefit that is given freely to illegal immigrants.

Citing conflict with federal law, Gov. Gray Davis vetoed a bill last year that would have allowed undocumented students to pay in-state tuition at California universities, provided they had attended California high schools for three years and were actively seeking legalization of their immigrant status.

A version of the bill has been reintroduced by its author, Assemblyman Marco Firebaugh (D-Los Angeles), and in his meeting with Fox this week, Davis promised Fox he would seek solutions. But Davis also warned that legal obstacles remain firm.

The issue is “frustrating and heartbreaking,” said Diana Michel, Davis’ undersecretary for education. The tuition barrier is really just the beginning of a lifetime of daily problems if they fail to secure legal status, she said, adding: “It’s not just this issue of post-secondary education.”

In Los Angeles schools, though, the legal issues are obscured by the swath of pain and anger that the policy cuts through the ranks of senior classes.

The number of students affected is hard to determine. Officials at Huntington Park, Garfield and Roosevelt high schools estimated that 10% to 15% of their seniors may be undocumented. At Belmont and Franklin, estimates were as high as 25% or 30%. But educators acknowledge that the numbers are based mostly on guesswork rather than hard statistics.

Many teachers echoed the perception that undocumented students are disproportionately high achievers scholastically, but this, too, is difficult to test. Some students drop out, or never come to anyone’s attention.

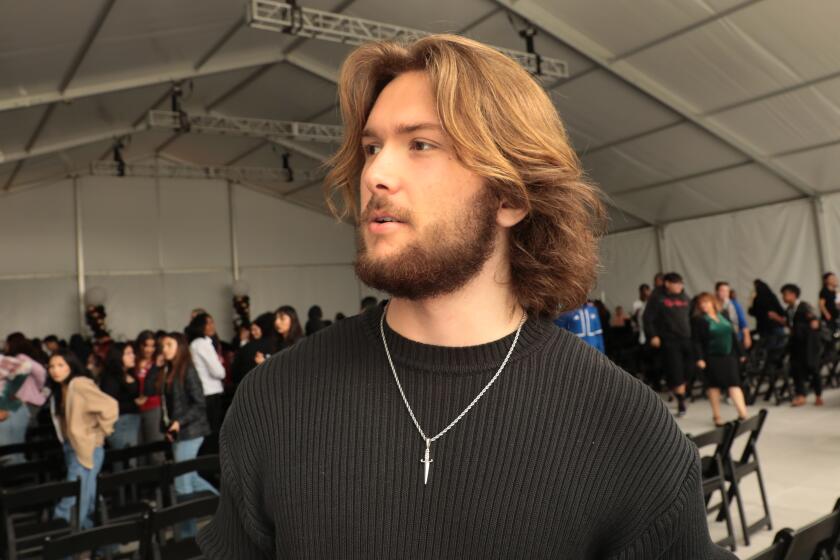

But one illegal immigrant at Roosevelt--a soccer player with such high science marks that he aspired to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology--said he believes many kids like him try harder.

“I thought maybe there would be some hope if I got straight A’s,” he said.

Stories of undocumented honor students, yearbook editors and athletes abound. Two large urban Los Angeles Unified high schools have had valedictorians in recent years who were illegal immigrants. Franklin counselor Sally Conway said that nearly every year five or six such students make the top 5% of her senior class.

This year’s class of L.A. Unified graduating seniors includes a 4.0-student at Roosevelt trying to win an athletic scholarship because he heard college coaches can bend rules for students like him; a 3.8 student at Belmont who says she wants to be civil rights lawyer; and an honor student and cross-country runner at Roosevelt who says she wants to find someone to marry so she can get her papers.

There is also Brenda Pintor, one of a few students who allowed her name to be used in this story. Her father is a legal resident awaiting his citizenship interview in a month, and she believes she will soon get documents.

Pintor, a Garfield student in the Advanced Placement program and a founding member of the girls’ golf team, developed leukemia last year. She spent six months in a hospital, completing some course work from bed. When she felt strong enough, she volunteered to help sick children who were hospitalized with her.

The disease now in remission, she has managed to finish high school on time and has been accepted to UC Irvine.

“I want to feel a part of this place, to be successful, to help my community, and California,” she said.

One undocumented Roosevelt senior, who has gone to California public schools since kindergarten, described how she realized suddenly that she wouldn’t be able to attend college after a teacher alluded to the tuition rules in class.

“It changed my life totally,” the student said, her mouth trembling as she fought back tears. “I used to be an A student. But I just dropped everything. I don’t get good grades anymore.”

A Garfield senior with a 3.7 grade-point average and a love for computer science kept pausing and taking deep breaths as he talked about not going to college. “I just don’t know what to do,” he finally said, almost whispering.

Counselors and teachers struggle with their feelings, too.

“What are we supposed to do? Tell them everything is going to be OK? Everything is not going to be OK,” raged Steve Zimmer, a social studies teacher at Marshall High School.

Zimmer said one of his undocumented students, a girl with a 4.0 grade average, is now working in a factory.

Educators and administrators acknowledged a strong temptation to try to bend the rules when confronted with such students. A few educators admitted skirting the law. There are stories of people helping students set up phony marriages, of college officials quietly turning a blind eye.

Other teachers described trying to do everything they could legally to help such students--chiefly by seeking the rare scholarships that don’t require legal U.S. residency. One counselor had even held fund-raisers in her home.

But when asked about the law’s merit as policy, complicated views emerged. Teachers and students advocated solutions ranging from opening the borders to locking them and legalizing people already here.

Immigrant advocates hold that most of these students will never return to Mexico or other countries, and tend to leave them out of the debate entirely. But in interviews, both teachers and undocumented students questioned Mexico’s obligation to these young people.

“How come [Fox] doesn’t help us?” said an undocumented Garfield student from Mexico. “The presidents should talk to each other and agree to something.”

Other students and educators point out that the situation in local high schools results from a contradictory mix of immigration policies: a legal right to attend primary and secondary school, but not college.

“It’s terrible,” said Julie Neilson, college counselor at Garfield. “We have created this.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.