Wild knights on Broadway?

Eric IDLE’S stiff-as-a-board leg is stretched out before him like an Arthurian battering ram barging its way toward the Holy Grail.

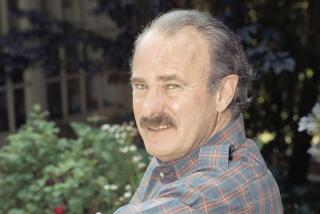

He’s wheelchair-bound after knee surgery, but his voice -- perhaps the only one in existence that combines the ease and snobbery of the Queen’s English with the pugnacious provincialism of every besieged little man -- is going at full throttle. His small eyes -- the shifty properties of which are forever branded on the brains of all obsessive fans of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus” -- dart around quizzically.

He’s careening wildly through the Paris hotel in Las Vegas, looking more like the propagator of a whacked-out Python sketch than the architect of “Monty Python’s Spamalot,” the most anticipated new musical of the 2004-05 Broadway season. The show, directed by Mike Nichols and starring David Hyde Pierce, Hank Azaria and Tim Curry, begins performances in Chicago on Dec. 21 and plays through Jan. 23. The New York opening follows on March 17.

“Spamalot” is based on -- or, in Idle’s savvy, disarm-any-potential-criticism-by-first-making-it-yourself language, “lovingly ripped off from” -- the troupe’s 1975 film, “Monty Python and the Holy Grail.”

In Las Vegas, the sight of a Python on wheels leaves casino patrons utterly unfazed.

Idle is in Vegas for the opening of “We Will Rock You,” the campy British musical featuring the music of Queen. The opening has drawn a plethora of B-list celebrities, aging British rockers and assorted English showbiz types who’ve flown in from London to support the writer-director, Ben Elton.

Idle is friends with Queen’s onetime manager. And he’s on the rent-a-celebrity list: He gets a free suite in return for trolling the red carpet.

The 61-year-old Idle is nice to the many Python fans leaning over the shrubbery to shake his hand. But he does not easily inhabit the role of beloved-but-faded comedy veteran at someone else’s opening of a second-tier show.

Heck, he’d just done his own second-tier show. “The Greedy Bastard” bus tour was an intentionally ragtag touring compendium of Pythonalia bereft of appearances by other Pythons, living or dead.

He did that tour for complicated reasons -- re-creating youth, cementing a legacy, accepting his fate that once a Python, always a Python. Most of all, he needed to prove himself.

The stakes surrounding “Spamalot” are much higher. But Idle’s reasons for doing it are much the same.

The “Holy Grail” film had mainly been Terry Jones’ idea. He had talked the rest of the Pythons into doing it. But this musical has been conceived, written, spearheaded, promoted, revised and dragged by its scruffy neck into existence by Idle.

If it hits, it may end up playing to millions of people. But the audience Idle cares most about numbers only five -- John Cleese, Terry Gilliam, Michael Palin and Jones. And Graham Chapman, who looks on from beyond the grave.

“Eric is more invested than the rest of us in this thing,” says the typically dry Cleese over the phone from his office in Santa Barbara some days later. “Thank goodness. The rest of us wouldn’t want to have to work that hard.”

The financial arrangements, Cleese says, take that into account. “Spamalot” is produced by Ostar Boyett Productions, with the Pythons sharing the potential booty with various other investors. Idle gets the lion’s share of the Python cut from “Spamalot” early on; the other Pythons’ share kicks in if it turns into a multi-company hit. This is Eric’s party; he is doing the work and taking the risk.

And, of course, if the show tanks, it will be Idle taking the hit to pocketbook and ego.

There is an Anglo American ocean of Python obsessives, many of whom can be found on the Internet at all hours, reciting lyrics and reliving classic sketches. But perhaps the most qualified Boswell is Kim “Howard” Johnson of Ottawa, Ill. The author of numerous books on the Pythons, Johnson hung out with them all, on and off, for decades.

“Eric was sort of the loner in many ways,” Johnson says, noting that the other Pythons tended to write in pairs. “He was behind the other Pythons in school. He was a bit overshadowed by them.”

So that’s why Idle never really moved on like the others? “He went to Hollywood,” Johnson says, “and found that people there had a limited idea of what an ex-Python should be doing.”

All of them worked according to their own silly but nonetheless carefully defined universe. Cleese and Chapman usually played the authority figures. Jones played the sleazeballs. Palin did the downtrodden weirdos. Gilliam played Gilliam. And Idle always played the cheeky striver.

Talk about typecasting.

If you don’t get too uptight about the minor difference in their numbers, the history of Monty Python has a lot in common with that of the Beatles. Perhaps that explains why the late George Harrison was one of Idle’s best friends.

Both groups were composed of cheeky lads who had a long creative run; both were consummate innovators who changed the form of their art; both smashed the perceived cultural barrier between Britain and the United States; both came to a premature end.

There were big differences, though. The Beatles did not inspire the word for junk e-mail. And the Pythons own all their material.

“The smartest advice we were ever given was ‘Get control of the material,’ ” Idle says. “Instead of getting the money, we got the masters.”

As it stands, the Pythons have collective control and veto power over all projects that use their name and material.

“Each Python has control only as long as they are living. Wives get the money, but not the veto,” Idle says. “We shall keep control of our legacy until the last Python kicks the parrot.”

But they haven’t really used Python material in the last 20 years. “Sometimes Python things float past us on a fax,” Cleese says, a tad wearily. “But no, nothing significant has ever really got off the ground.”

Until this month in Chicago.

In the beginning

The Pythons started gradually in the late 1960s. Chapman, Cleese and Idle were at Cambridge University; Jones and Palin went to Oxford.

The Pythons-to-be appeared in various permutations in such shows as “The Frost Report,” “At Last the 1948 Show” and a hysterical children’s show called “Do Not Adjust Your Set.”

Eventually, all six ended up together and got money from the BBC to do 13 episodes of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus,” first broadcast in 1969. (Idle was responsible for encouraging the lone American, Terry Gilliam, to join.) The episodes blended domestic sketches, absurdist animations, running gags and silly walks that became their signature.

Memories of the Pythons often are faulty. Many people think of them as funny on their feet. In fact, they didn’t improvise at all. “We always wrote everything down,” Idle says.

“Time plays tricks,” observes Hyde Pierce, who has gone from a supporting role in “Frasier” to a starring role in “Spamalot.” “You tend to remember the outlandishness of the situations and forget how straight they played it.”

Then there’s the matter of the simpler era. It was not simpler just because early Python fans happened to be young. They just think it was.

“You start looking back,” Cleese says, “then you find yourself realizing, ‘Oh, yes, that was the time of the Vietnam War, wasn’t it?’ Somehow the anxious-making things get forgotten.”

The Pythons moved into film -- as well as books and other cross-platform ideas that were unusual in that day -- much more quickly than most TV comedians. The first Python movie, “And Now for Something Completely Different,” preceded the second season of “Circus.”

After the show’s third season, in 1972-73, Cleese felt too constricted by the Python format to continue as a member. A fourth “Flying Circus” season was made without Cleese in 1974. Monty Python wasn’t an immediate smash in the U.S. Not only were early episodes shown here well after their first airing in Britain, but it took time for U.S. audiences to get the joke. “It was a cult-style thing,” Johnson says.

“Something Completely Different” was intended as the Pythons’ grand entree into the U.S. market, but it was “Grail” that exploded the troupe’s reputation. Zaniness and the odd American affection for all things medieval proved an irresistible combination.

In England, the much edgier “The Life of Brian” is far more popular. And Cleese is much better known in his home country for his later work on the sitcom “Fawlty Towers” than for anything he did with the Pythons.

But in the U.S., Cleese means Python and “Holy Grail” is the Holy Grail.

“Everybody in America has seen it,” Idle says. “At least everybody who went to college.”

A lovely bunch of coconuts

“The appeal of Python in school was that these were guys making elaborate comedy routines out of your silly thoughts,” says Azaria, a key cast member in “Spamalot.” “They could take all of that repressive upbringing and spit out something really funny.”

“Grail” follows King Arthur through various and sundry adventures and distractions as he seeks knights to accompany him on his quest for the Holy Grail.

The budget was pitifully small. When it became clear that horses were going to be out of the question, the famous device of having a fellow run along clicking coconut shells to simulate the sound of hoofs was born.

The screenplay’s original intent was to set half the movie in medieval times and the other half in the modern day. That got shelved -- for the most part.

And the ending? It really isn’t an ending. The film just ends.

“Grail” was a success on both sides of the pond, but the boffo Python era really didn’t last long. After “Meaning of Life” in 1983, the Pythons, in Idle’s words, “fled in different directions for various courses of therapy.”

Cleese did movies, including “A Fish Called Wanda” (with Palin). Palin became known as a writer and an esoteric globetrotter. Gilliam directed films, including “Brazil.” Jones became a documentarian, children’s author and newspaper columnist for the Guardian. Chapman, who struggled with a variety of demons, was diagnosed with cancer and died in 1989.

There was talk of reunions but none materialized. Idle tried to put something together in Vegas as a tribute to the old Python material. But it fell apart.

There was a half-baked Python reunion of sorts at the Aspen, Colo., comedy festival in 1998, which was taped for HBO (Chapman appeared in the form of an urn of ashes) and a 30th anniversary special with each doing separate tapes for the BBC in 1999. But mainly the other Pythons saw little point in reliving the old days.

Idle starting doing Python material by himself on tour. The others were happy for the checks.

So that was that.

But a turning point came in 2003. All the Pythons except Cleese appeared at the Concert for George, a high-profile charity tribute to the deceased Harrison at London’s Royal Albert Hall. The Pythons got an especially rapturous reception.

Idle, who was deeply moved by the night, began to develop an understanding of the seminal place of Python material in the popular consciousness.

More than anything, the response convinced Idle that a theatrical “Holy Grail” (with which he’d already been tinkering) might fly. With film composer John Du Prez (“A Fish Called Wanda,” “Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles”), who had long-standing connections to the Pythons, Idle started working on a musical. “Mortality,” Idle says, “is a very real thing.”

He ran his ideas past the other Pythons. They didn’t exactly rush to his side but nonetheless told him to go ahead. “He sent us all a kind of general note and a tape of the songs,” Cleese says. “I remember making some suggestions. So did the others.”

Idle took the critiques to heart. He tossed out songs that weren’t funny, or that the other Pythons thought weren’t funny, replacing them with new ones. Eventually he had a set of musical numbers that everyone -- even Cleese -- found funny.

Then Idle called director Nichols, his friend of more than 20 years. “The time is right,” Idle recalls telling him.

Nichols (“The Graduate,” HBO’s “Angels in America”) says he wasn’t thrilled to get the call. “I really didn’t want to do a Broadway musical. I never have a good time doing them,” says Nichols, whose only significant Broadway musical credit is 1966’s “The Apple Tree.” “But in this case, I was stuck.”

The addition of his blue-chip name sent the project into another stratosphere. Potential investors now had the lure of Python and a marquee-name director. And then there was the very promising precedent of Mel Brooks’ “The Producers.” Actors got a whiff of the plan and started to telephone in droves.

“I called my agent,” Hyde Pierce says. “I told him I don’t care what the part is, I just want to audition.”

So what will “Spamalot” look like? The plot has been a closely guarded secret, but some things are leaking out. Although Idle will not be appearing in the show, Cleese will be playing the voice of God. On tape.

“I think we have some very nice moments,” Idle says. “Singing cows. Things like that.”

In essence, the show will have the same plot as the movie, with some of the same lines and the original two songs. But the character of King Arthur has been greatly expanded. Since Idle has beefed up the war-and-conquest metaphors, Lancelot might take on more than a passing resemblance to Donald Rumsfeld.

And there has been a big expansion in the role of the Lady of the Lake, who has gone from a quick reference in the film to a full-blown diva played by Sara Ramirez.

And the ending? “We had a new one just today,” Idle says. “That was No. 6.”

According to Nichols, the eternal Python love of self-parody also has been turned into a lot of spoofing of Broadway styles. There’s a song that makes fun of the shows of Andrew Lloyd Webber and others, and theatrical conventions get lampooned in the style of the original movie, in which “Scene 24” gets mentioned about every five minutes for no clear reason.

The biggest difference will be the music. Every famous piece of shtick now has its own custom ditty. Du Prez, who wrote the music with help from Idle, says the melodies are far from comic.

“In Python,” Du Prez says, “I’ve always felt the music has to be the straight man, so the lyrics can be funny.”

In addition to the book, Idle has written all of the lyrics. The success of the show hinges on how they’re received. “We’ve written this thing three times, and Nichols still doesn’t like it,” Idle says at one point. “I’d have gone into rehearsal three texts ago.”

Says Nichols: “There is one criterion: Is it funny or not? If it’s not funny, it has to go. If it is funny, we can move on to the next scene. There’s no discussion of nuance or jargon or anything at all beyond that.”

Idle will likely be spending Christmas with his wife’s family in Chicago, tossing out songs and putting in new ones in the middle of the night.

“Eric is a philosopher,” says Nichols, a man not given to lavishing praise. “He’s so highly intelligent, so highly educated and yet also deeply curious. He has enough grasp of the physical universe to be funny about it. Cleese is equally brilliant and equally curious, but he’s a little bit in another world.”

“Spamalot” starts in Chicago because of Idle. He likes the city and, after all, “Spamalot” is his show. And he has a lot to prove.

“Wellington knew his terrain,” Idle says, “before he stood at the back and said, ‘Die.’ ”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.