Why you should stop worrying about the Obamacare ‘death spiral’

Among the many reasons often put forth for why the Affordable Care Act is supposedly doomed to failure -- put forth with hand-wringing by the act’s supporters and with gleeful anticipation by its opponents -- is the sinister-sounding “death spiral.”

Like many concepts in the health insurance business, this one is highly complicated, nuanced and easily reduced to a sound bite. The Kaiser Family Foundation has now come out with a paper explaining why it’s not the threat it’s made out to be.

As it applies to the Affordable Care Act, the “death spiral” is what would happen if the individual insurance exchanges fail to sign up enough young, healthy members to adequately subsidize their older, sicker members.

To cover their higher expenses, the plans would have to raise premiums, which would drive more younger customers out of the insurance pool, which would force premiums even higher, which would drive younger customers out ... etc., etc. Eventually only sick people are in the pool, the young invincibles (so-called because they think they’ll never need care) are all on the outside looking in, and the system collapses.

The received wisdom is that 40% of enrollees in the state exchanges have to be in the age range of 18 to 34. If enrollments meet the Congressional Budget Office projection of 7 million, then 2.8 million would have to be in the target range. That’s why so much attention has been paid to the age breakdown of enrollees so far.

The death spiral is easy to envision, which is why it has become a staple of the Obamacare discussion on cable TV and in the comment threads of news websites. The Kaiser Foundation’s judgment is: “highly unlikely.”

To explain why, its analysts Larry Levitt, Gary Claxton and Anthony Damico conjured up two scenarios in which enrollments of healthier people fall short of the goal. They also factored in the age-related premium differential permitted under the ACA -- older customers can be charged up to three times as much as younger enrollees. That alone does much to mitigate the impact of any age imbalance.

In the first scenario, signups of young customers fall 25% below projections -- in other words, they compose 33% of the risk pool, instead of 40%. In that case, the analysts find that insurer costs (benefits, overhead and profit) exceed premiums by 1.1%.

If they enroll at a 50% lower rate -- that is, they’re only 25% of the pool -- then costs exceed premiums by 2.4%. In both scenarios the costs cut into insurer profits, but they’d still leave insurers in the black. The Foundation says insurers would probably raise premiums to cover the shortfall in 2015, but even a 2% premium increase wouldn’t be enough to trigger the death spiral.

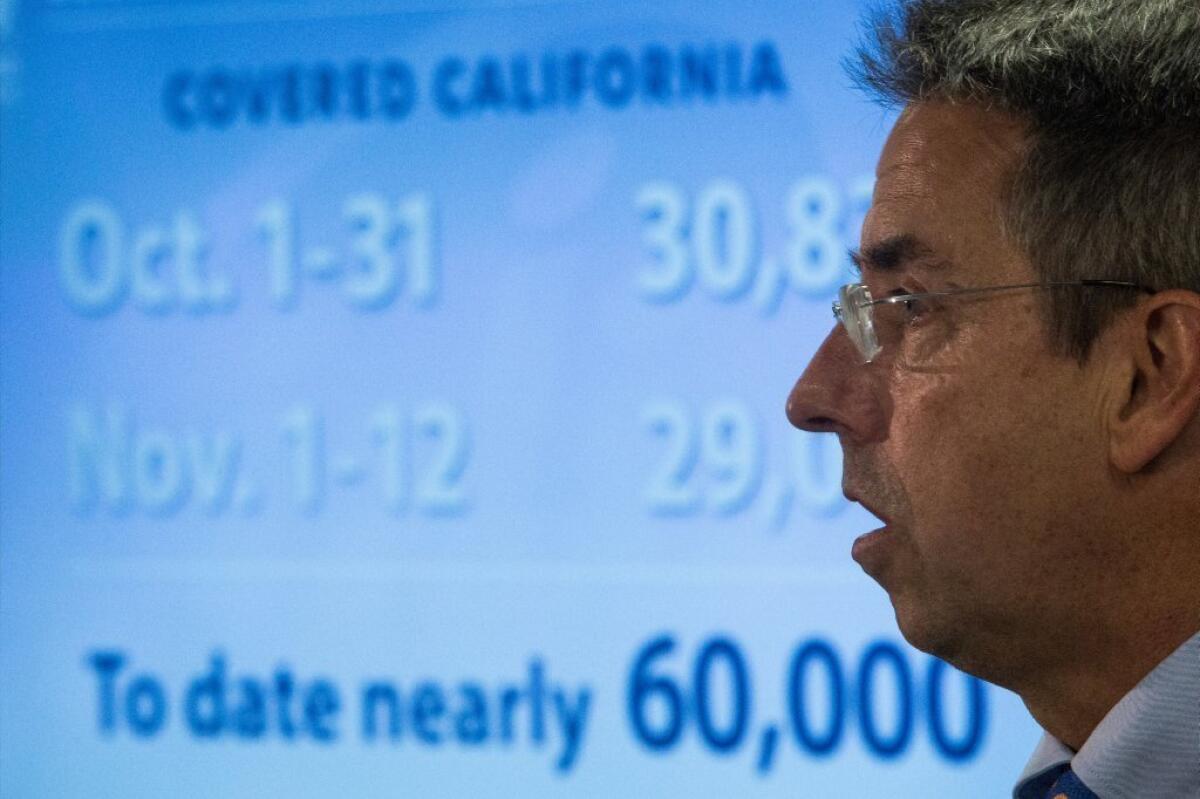

The analysts point out that their scenario 2 is a worst-case scenario. It tracks the experience of the California health exchange, Covered California, which has reported 21%-22% of enrollments falling into the 18-34 range in October and November. But health experts expect younger people to apply and enroll later in the enrollment cycle than older residents, so they anticipate the ratio to rise.

Kaiser points out that in its own survey of California’s uninsureds, 58% of those 18-34 said they planned to buy coverage in 2014. Moreover, the No. 1 reason for not having it in the past was its cost. That’s a good sign, for a large proportion of young people are likely to be eligible for government premium and cost-sharing subsidies, which could reduce the cost of their coverage to almost nothing.

Premium subsidies are available to people earning up to 400% of the federal poverty line. For a single person, that’s $45,960 -- well above the median income for people in that age range, which was about $30,500 in 2012, according to the Census Bureau.