Review: ‘Last Sentence’ puts a period on life of a Hitler critic

“The Last Sentence,” the fine new biographical film by Jan Troell, is a more sophisticated work than it appears about a man whose life was more complicated than the world knew.

That man, Torgny Segerstedt, was a Swedish newspaper editor celebrated in that country for his prescient, persistent and unapologetically fierce criticism of Adolf Hitler, beginning as early as 1933 when the German leader was appointed that country’s chancellor.

But anyone expecting a worshipful film is underestimating Troell, one of the masters of Scandinavian cinema whose previous works include the Oscar-nominated pair “The Emigrants” and “The New Land,” as well as Segerstedt himself, whose own words start the film: “No human being can withstand close scrutiny.”

It’s also accurate to say, however, that those expecting some kind of now-it-can-be-told expose will be disappointed as well. Clear-eyed and evenhanded, the director (who also shares credit on the writing, cinematography and editing) focuses on presenting the dynamics of a complex life, not on the passing of judgment.

That attitude is typical of Troell, whose last film was the memorable “Everlasting Moments.” Measured and beautifully modulated, the 82-year-old director has the kind of sureness and fluidity that is easy to underestimate. But it’s difficult not to be impressed by the results.

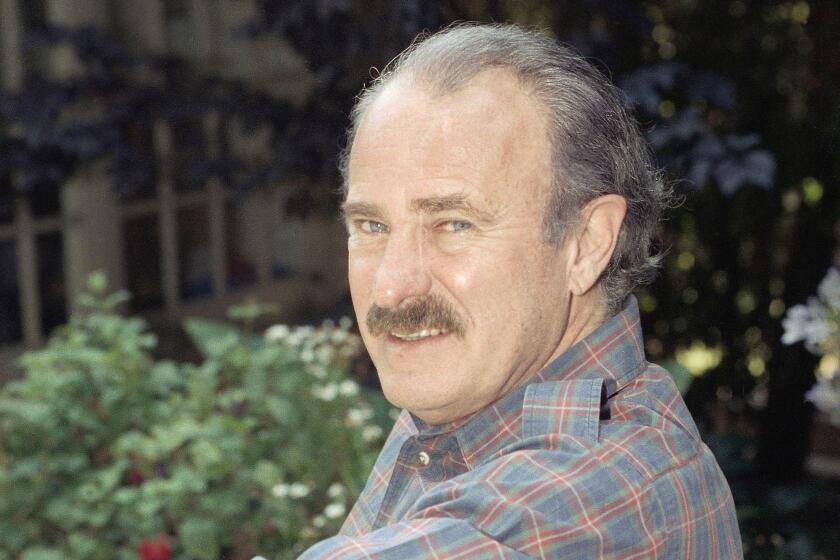

Also known as a fine director of actors, Troell has an especially strong cast here, starting with the leonine Jesper Christensen (familiar as a James Bond villain) as the editor whose impeccable public life was not matched in the private sphere.

Shooting digitally for the first time, Troell (working with cinematographer Mischa Gavrjusjov) simultaneously moved into the past by making “The Last Sentence” in luminous black and white. He takes palpable pleasure in conveying us back to a time when an unhurried style of upper-class personal life owed as much to the 19th century as the 20th.

Troell seems to get special enjoyment out of putting the specifics of 1930s journalism on display, as Segerstedt is introduced dipping a pen into an actual inkwell and writing an editorial that will be set in type by an ancient Linotype and read on a proof pulled by hand.

That 1933 editorial, with the headline “Mr. Hitler Is an Insult,” was the opening shot of a campaign against the German leader that was so vitriolic that Nazi leader Hermann Goering sent the editor a telegram suggesting he lay off.

Applauding Segerstedt’s courage is his publisher, Axel Forssman (Bjourn Granath), and Forssman’s Jewish wife, Maja (Pernilla August, whose early career included “Fanny and Alexander” and “The Best Intentions”).

Maja is not only the boss’ wife, she is also Segerstedt’s very public mistress, a situation that disturbs and aggravates the editor’s neurotic wife, Puste (Ulla Skoog, an actress apparently known for comedy), who has not given up on the vain hope that she will once again become the object of her partner’s affections. “You two have your Hitler,” she plaintively tells her husband. “What do I have?”

Though Segerstedt’s opposition to Hitler now seems almost a given, one of “The Last Sentence’s” fascinating aspects is showing how unpopular it was in a Sweden that was officially neutral during World War II and determined to stay that way.

Fearful that Segerstedt’s unbridled attacks might drag his country into war, Sweden’s prime minister and its king, Gustaf V, are shown trying to get Segerstedt to pull back. But a man who believed not telling the truth made you “not only the hostage to a lie but its promoter” was not to be dissuaded.

This kind of admirable single-mindedness, we come to see, did not work in the editor’s private life. Segerstedt does not treat his wife well and does not understand why Maja and Axel, who are perfectly content with their open marriage, would want to end it just to make him happy.

“Torgny is very moralistic about his immorality,” Maja says to a friend at one point. That turns out to be a shrewd observation about a man whose complicated life gets the adult examination it deserves.

-----------------------

‘The Last Sentence’

No MPAA rating

Running time: 2 hours, 6 minutes

Playing: At Laemmle’s Royal, West Los Angeles

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.