Movie review: ‘Twelve’

Twenty-five years ago, Demi Moore huddled in an empty room with billowing curtains for Joel Schumacher’s “St. Elmo’s Fire” and an iconic if cheeseball visual cue for spoiled-youth loneliness was born. In “Twelve,” the director’s latest dive into the indiscretions of adolescent brats, the possibilities are endless: a drug-addled teenage girl’s hallucination that her stuffed bears are talking to her, a broodingly handsome drug dealer’s mopey timeout in a street-construction hole or maybe that hair-trigger rich kid in the police interrogation room breaking down on a phone call from absent Daddy. So much to choose from.

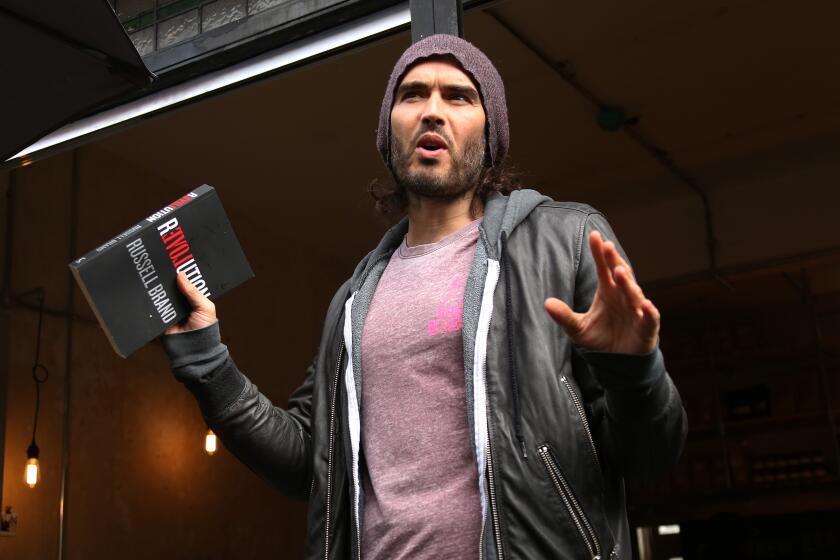

A slickly dark-edged pity party for damaged Upper East Side adolescents, “Twelve” is adapted from a 2003 novel that earned a good measure of acclaim because its author, Nick McDonell, was just 17 when he took aim at his peers. McDonell’s familiarity with the hedonistic ups and downs of Manhattan’s entitled youth gave the book some “Less Than Zero”-style cred, but Schumacher is at the other end of the age spectrum.

A veteran glitzmeister with a spotty track record mixing style and emotional depth, his handling of the material — adapted by Jordan Melamed — is less harrowing wake-up call than fast-moving picture window on the smorgasbord of teenage sin. (The title refers to a powerful new drug earning hot status among the film’s moneyed pleasure-seekers.)

The action takes place over a long weekend of depravity and tragedy, bookended by a couple of back-pages gunshots in a Harlem hallway at the beginning and a citywide headline’s worth of them during a climactic townhouse bacchanal at the end. In between, the kids are not all right, but OMG, they suffer beautifully. When we’re allowed to appreciate their predicaments, that is. Because although we meet more than a dozen characters — including trench-coated pusher White Mike (“Gossip Girl” star Chace Crawford), fame-seeking, manipulative hottie Sara (Esti Ginzburg) and self-destructive party girl Jessica (Emily Meade) — more accurately, we’re told everything about these characters thanks to the ubiquitous presence of narrator Kiefer Sutherland. His near-constant, growly, “Dragnet”-like briefings — background info, in-the-moment headspace, and philosophical context — are the surest sign the filmmakers had little confidence in the communicative power of the apprehensive faces on-screen.

Which is a shame, because the young cast has its standouts, including Curtis Jackson as White Mike’s supplier, Emma Roberts as sweet-faced good girl Molly, Rory Culkin as recessive hanger-on Chris and Billy Magnussen as Chris’ unhinged older brother Claude, whose left-field purchase of a samurai sword is the kind of freaky act of roiling insecurity that in a better filmmaker’s hands would play as disturbing rather than campy.

Then again, for all the cautionary trappings inherent in a downward spiral like “Twelve,” it ultimately falls victim to another kind of addict, in that Schumacher can’t keep himself from the kind of vibey camera and editing flourishes that facilitate only viewer numbness: slo-mo for cool, herky-jerky for loss of control, white backgrounds for momentous flashbacks or silly detours like the contents of someone’s pockets. The stylistic distractions are such that when one character learns of the shooting death of his cousin, it doesn’t immediately trigger the fact that this was something depicted in the first act. Consider “Twelve” its own memory-retarding narcotic.

calendar@latimes.com

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.