Frederick Wiseman, documenter of life

How do you describe someone who’s directed 38 films, 36 of them documentaries, a filmmaker whose work provides an expansive and unparalleled portrait of how people and institutions function in the modern world?

There really are only two words you can use: Frederick Wiseman.

“I like working, I work all the time. It keeps me off the streets,” the director says wryly of his investigations, which range in length from the 73-minute “High School” to “Near Death’s” nearly six-hour examination of an intensive care unit. “It’s like a course in adult education and I’m the alleged adult.”

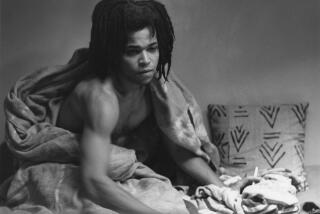

The director, who is 80 but could easily pass for someone a decade younger, is in Cannes for the world premiere of his latest work, “Boxing Gym,” an engrossing look at what goes on inside Lord’s Gym in Austin, Texas. It’s an establishment with a clientele that includes professional fighters, women and kids, all looking to master the sweet science and, in the process, do a lot of hitting. “It’s the beast in action,” Wiseman says as talk turns to scenes of furious punching. “We’re a violent creature, though the fact that it’s ritualized in boxing means it seems more or less under control.”

Although he didn’t plan on such an extensive filmography when he began with “Titicut Follies” in 1967 — “If someone had said to me then that I’d do 38 films, I would have said ‘Don’t put me on,’ ” — one thing led to another, including subjects as varied as “Basic Training,” “Welfare,” “Domestic Violence” and two films on ballet.

“There’s no shortage of really good subjects, given human behavior as it is, and I keep a running list in my head of what the two or three next ones might be,” Wiseman says. Sometimes, the idea comes all at once — as with his next project, the arrival of a new choreographer at the venerable Paris nightclub Crazy Horse — and sometimes the choice is more deliberate. He followed “State Legislature,” a look at the talky work of Idaho lawmakers, with the more action-oriented “La Danse,” about the Paris Opera Ballet, and “Boxing Gym.”

“I make a guess that what goes on is going to provide me with enough footage, something I think I’d like to spend a year on,” he explains. “The analogy for this kind of filmmaking is Las Vegas: You roll the dice but you don’t know what is going to happen.”

What Wiseman is at pains to guarantee is that “I approach everything with an open mind. What I do is a response to what I’ve seen, not an attempt to prove a preexisting thesis. Human behavior is so complicated, and my goal is to begin to suggest that complexity. If I can say it in 25 words or less, why make the movie? And if people give me permission to film them, I feel obligated to accurately reflect what I’ve learned.”

Once he picks the subject and the particular establishment that reflects it, Wiseman tells those involved, whether it be the Kansas City police or the habitués of Lord’s Gym, “a version of the following: I plan to hang around six or eight weeks, I don’t stage anything, and anyone who doesn’t want to be photographed just has to tell me. I collect a lot of material [100 hours for the 91-minute “Boxing Gym”], I spend eight months to a year editing and then it will be on television and might be shown theatrically.”

One thing that definitely won’t be part of the mix is a voice-over commentary: The absence of narration is one of the hallmarks of Wiseman’s style. “That reflects my interest in fiction,” the director says. “I don’t like it in a novel when some omniscient narrator tells me what to think about the characters before I’ve even met them. My films put you right in the middle of these events, they make you think through your relationship to them in order to understand the action.”

A key way that Wiseman puts viewers in the middle of events is to be in the middle of them himself. He does his own sound recording and, in addition to a cameraman, uses only a third person to change the film magazines. “It’s a very nice way to make a movie,” he says. “It’s a technique geared to move quickly when you decide whether something is worth shooting.”

Once the filming starts, what the director characterizes as “a kind of a mutual sizing up goes on. I’m trying to figure out the situation, and the people I’m filming are trying to figure out ‘Is he a nice guy? Can I trust him?’ One reason why people do trust is that we all think what we’re doing is OK, we don’t see it the same way as someone else. The extent of that disparity allows you to make films and record an enormous diversity of behavior.”

Wiseman has worked with the same cinematographers multiple times — John Davey, who shot “Boxing Gym,” is one of only four he’s used — and that familiarity is key to how they operate. “We have signals that we use, and we constantly have one eye on each other,” the director explains. “Deciding what to shoot is a combination of instinct, judgment and luck. You have to take the risk of shooting a lot, you can’t stop and start. The one rule I’ve learned is that the most interesting things will happen when you’ve stopped.”

Just as critical as the shooting for Wiseman is the editing process. On the most pragmatic level the director says, “the thing that helped me most in learning about filmmaking is editing the films myself. If I find myself tearing what’s left of my hair out because there’s no wide shot, no cutaway. I remember that the next time I’m shooting.”

On a more artistic level, Wiseman describes editing as “a second opportunity to recognize the implications of what you’re shooting, to try to figure out what’s going on in human terms.”

“Before I sign off on the editing, I have to be able to go through the film shot by shot and have a reason to myself why one shot follows another. It may be character development, foreshadowing, the passage of time, all the issues involved in other dramatic forms. It may not be obvious if you haven’t looked at the film 500 times, but you’re dealing with something more than the literal arrangement of sequences. If my films work, one of the reasons is that they’re structured by the editing from beginning to end.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.