Eiko and Koma share a lifetime of choreography

Reporting from New York

High above the city, with a clear view of the icy streets below, the illustrious choreographers and dancers Eiko and Koma began a recent morning in their midtown apartment deciding what photographs should go into a new book about their work, soon to be published by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

It complements their current tour’s “Regeneration” program, which comes to Los Angeles this week. Since the early ‘70s, Eiko and Koma have created bold, almost still, theatrical works of elemental power. Dressed simply or naked, the married couple evoke a primitive world where primal emotions are conveyed wordlessly.

“At first, we didn’t want to be involved in the book or the tour,” Eiko says, delicately sipping tea. “We thought that it sounded as if we were finished,” explains Koma, an energetic man with unruly, thick, black hair. “But then,” she says, finishing his sentence, “we saw that it would be quite the opposite. We look into the world — human lives, nature, and different species — and discover both the beauty and unreasonableness of it all. We care very much about what we say and dance about. We want to preserve and renew those things.”

The couple, who use only their first names, will perform “White Dance” (1976), “Night Tide” (1984) and “Raven” (2010), three milestones in their 40-year career, at REDCAT. The book and the tour give them an opportunity to share a lifetime of work, under the umbrella of “The Retrospective Project,” with “Regeneration” devoted to their dances and the book and exhibitions to their essays and video, art and sound works.

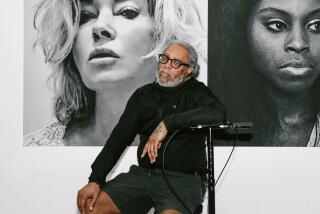

If not for their friend and advisor Sam Miller, president of the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, “The Retrospective Project” might never have gotten off the ground. A fan of theirs since the early ‘90s, when he directed the Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival, Miller liked the idea of applying the museum-gallery concept of a retrospective to their 40-year career and became the project’s producer. Explaining his enthusiasm for their artistry, he says, “I like how they manipulate space and time. I love having to commit myself to their experience and slow down and spend time in their time.”

Neither success nor age diminishes their daring. While most choreographers and dancers older than 50 wouldn’t dream of performing, let alone performing naked, Eiko, 58, and Koma, 61, exhibit fearlessness and good humor about the challenges. “Of course, our bodies are very different from 30 years ago,” he says, “and some people might think we should cover ourselves. We can’t do everything the same way we did then, of course. But it’s interesting to us to see how we adapt and what results. In a way, we’re celebrating how we have aged. Our vulnerability invites the audience’s empathy.” Pausing for a moment, she adds, “Every time we do a piece, we get to know more about it. The performance brings us new juice.”

Eiko and Koma’s living room looks empty enough to be a studio, with a barre against one wall and hanging above it an irregularly shaped mirror, framed by branches. A piano stands nearby and at the far end is a card table stacked with DVDs and CDs, some which belong to their two adult sons. But they confess to a lack of physical preparation for their performances. “We mostly use the barre for stretching or hanging laundry,” she says. He laughs and says, “Eiko couldn’t even ride a bicycle when I met her. Physical education was her worst grade.” She interrupts, “All we do is try not to have any accidents.”

They don’t choreograph together either, each one creating his or her solos alone. Standing up to demonstrate, Eiko illustrates with her hands, “I take just so much space to work and Koma takes just so much. We don’t overlap and or even know what the other one will do. When we end up together touching on stage, it’s only by chance. That’s not choreographed.”

Simplicity is key for them. They create settings resembling primeval or post-apocalyptic landscapes with which they appear to merge physically, sometimes including branches, dirt, straw and leaves as part of their sets. Their scores might be sounds of nature or drums and their costumes share the fluidity of the music, or they might perform in silence. Sometimes they wear robes, other times pieces of cloth patched together or nothing at all. From the beginning, they have given their works straightforward titles such as “Grain,” “Thirst” or “Tree.” Because the meanings are intentionally subtle, the titles serve only as indicators or as Eiko explains, “a way for us and the audience to stay focused. For instance, ‘Raven.’ It represents the black color and the scavenger nature of crows and all of us.”

Life mates, Eiko and Koma met as students in the ‘60s in Tokyo, both active protesters against the Vietnam War, the destruction of nature and the increasing commercialization of society. Turning to art to express their ideas, they became fascinated with the avant-garde theatrical movement, and came under the influence of Kazuo Ohno, a pioneer in Butoh, the Japanese avant-garde performance art usually performed in white face. In the early ‘70s, wanting to expand their knowledge, they took off for Europe to study with experimental choreographers Manja Chmiel in Germany and Lucas Hoving in the Netherlands. By the time they reached New York in 1976, they were on their way to developing their distinctive Zen-like dance style, trying it out by performing in art galleries.

When they first presented “White Dance,” no one knew what to make of it. Their faces painted white, they each wore different colors, Koma a bright red toga and Eiko, a kimono of muted shades, and moved more like animals and birds than human beings, to medieval music and Bach. The backdrop showed a moth projected on scorched sheets. “Even though audiences were surprised by us, there was a very good atmosphere,” Eiko says. “Certain people responded very deeply.”

Beate Gordon, who was then director of performing arts at the Japan Society in New York, and is now a consultant on Asian arts, was impressed from the beginning. “Then, as now,” she says, “they were very pure, very sincere, very truthful in their art and their daily lives. It is heartening that they are among the most successful choreographers, from every point of view, of our time.”

When they began programming “The Retrospective Project,” Eiko and Koma wanted to make sure every performance would be somewhat different. So they change the program from engagement to engagement, except for always including “Raven,” which meditates on our hunger for nourishment and intimacy. Made in collaboration with Native American musician Robert Mirabal and performed on a handcrafted, burned and scorched floor, its origins lie in their 1991 piece “Land.”

“We keep ‘Raven’ as a centerpiece,” Eiko says, “because we like to see how it looks surrounded by other dances. We enjoy going over everything again. Someday, we’d like to have our own museum and exhibit everything we’ve ever done.” Suddenly afraid that her wish might have sounded too grand, she clarifies, “It would be a very humble museum.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.