Manzanar pilgrimage takes on broad themes of democracy, civil rights

Masako Miki came to this picturesque landscape of snow-tipped mountains and desert shrubs Saturday on a mission of remembrance.

Miki, raised an ocean away in the seaside Japanese city of Kobe, never learned about the painful history embedded in this windswept stretch of the Owens Valley.

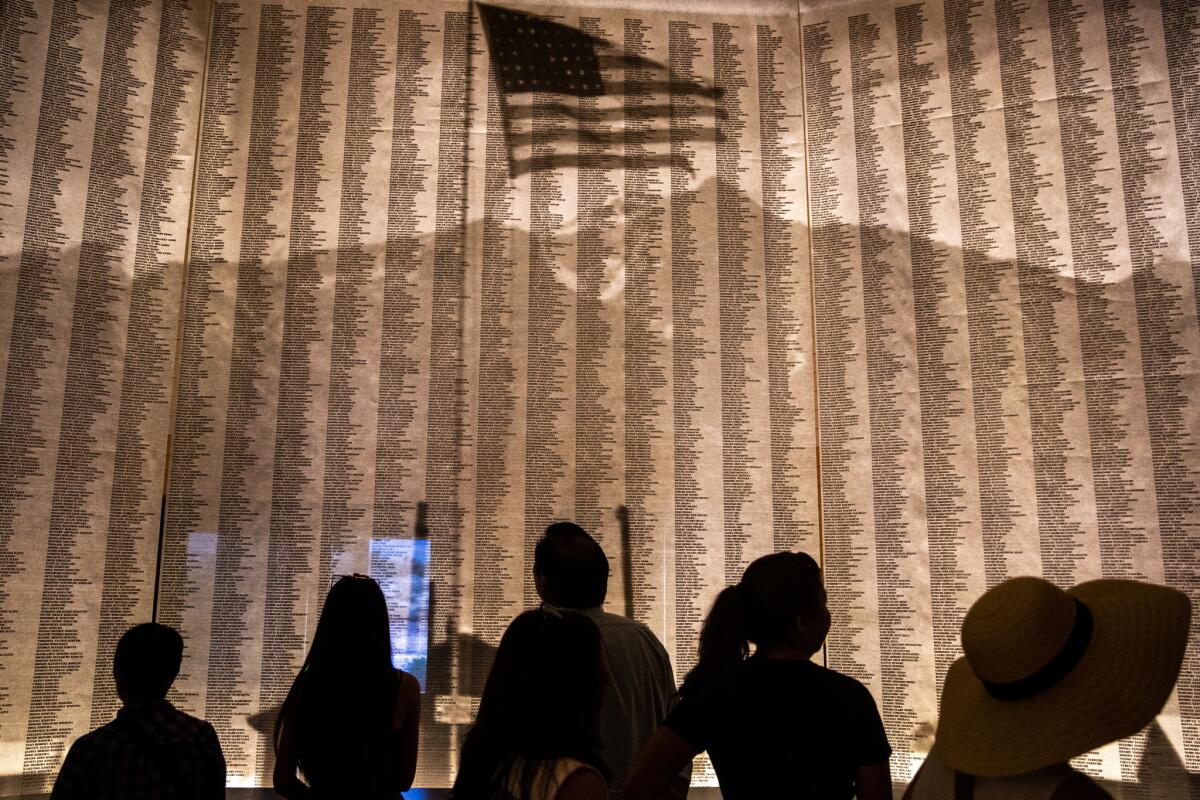

Only after she began working for a Japanese magazine in Los Angeles nine years ago did she learn that 120,000 people of Japanese descent — two-thirds of them U.S. citizens — were evicted from their West Coast homes and incarcerated here at Manzanar and nine other camps during World War II.

She was horrified, shocked and remorseful that her country’s attack on Pearl Harbor had helped fan the wartime hysteria and racism that led to the mass incarceration.

“I felt ashamed,” Miki said. “As a human being, I feel responsible to learn history and not repeat it.”

More than 2,000 people traveled to Manzanar on Saturday to mark the 50th anniversary of an annual pilgrimage to the site of the first and best-known wartime camp. They included a growing number of Japanese like Miki aiming to understand the experiences of Japanese Americans and rebuild connections between the two communities that were shattered by war.

But the meaning of Manzanar has morphed far beyond those two communities embroiled in the Pacific War. In an afternoon program, a multicultural slate of speakers drew connections with other communities as well: Muslims targeted by hate speech and travel bans; Latin American families torn apart at the border; African Americans harmed by racial profiling; American Indians fighting for access to their lands.

(Unbeknownst to the crowd, a white gunman who had written anti-Semitic screeds had just walked into a synagogue and shot into the congregation with a semiautomatic rifle, killing one and injuring three.)

Bruce Embrey, the son of a seminal activist who helped start the pilgrimage, urged vigilance against the rising threat of white nationalism and President Trump’s rhetoric about “invasions” of migrants and punitive border policies.

“Manzanar should not just be a symbol of what is wrong with our nation,” said Embrey, whose mother, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, was one of the first camp survivors to break the silence about the experience. “Manzanar should become a monument to our core values of democracy and civil rights. Our message is simple: Speak out, demand equal justice under the law for everyone no matter who they are or where they come from.”

Nihad Awad, a founder of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, told the crowd that he made sure his young children read books about American history, including the wartime incarceration.

But his daughter absorbed the lessons in a startling way: After 9/11, Awad said, his young daughter packed a suitcase, expecting that government agents would take her family away as they had once routed Japanese Americans from their homes.

“An attack on one community is an attack on all of us,” Awad said to thunderous applause.

That message of unity drew Gwen Humphries and Elizabeth Walker to travel from Victor Valley on Saturday to join the pilgrimage for the first time. Both retired educators, they said they had heard about the wartime incarceration for years but believed it was important to visit the site themselves at this particular political moment.

“Given the political climate right now and issues with people of color and from different countries, I think it’s important we remember how harrowing discrimination is and how it affected a huge population of American citizens who were put in a concentration camp environment just because of race,” said Humphries, who is African American.

Warren Furutani, a former state assemblyman, told the crowd that he and another student activist at the time, Victor Shibata, were inspired by marches of farmworkers to Sacramento and poor people to Washington, D.C., in the 1960s.

Searching for a social justice issue to build a march around, he began asking elders about the camps, which at the time they generally kept hushed up.

After realizing that the 220-mile trek from L.A. to the Owens Valley was too long for a march, Shibata suggested making it a pilgrimage to recognize the spiritual touchstone that Manzanar had become.

A moment marking the healing that has taken place in subsequent years, particularly between Japanese Americans and their ancestral country, occurred when Tomochika Uyama, consul general of Japan in San Francisco, offered greetings and appreciation in both English and Japanese for the chance to visit Manzanar for the first time.

That prompted traci kato-kiriyama, a Manzanar pilgrimage organizer, to exclaim, “How beautiful to hear Japanese spoken here!”

She told the crowd that the painful incarceration had led some of her family members to shun Japanese culture and language. “I had people in my family who did not want to speak Japanese or study it ever again,” she said.

Her family was not unusual. As news of the Pearl Harbor attack spread, many Japanese American families buried or destroyed anything that would mark them as loyalists to the now enemy state — ceremonial swords and dolls, books and photos.

FBI agents swarmed in and hauled away community leaders with no evidence of wrongdoing. Two months later, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced relocation and incarceration. Ultimately, U.S. officials issued “loyalty” questionnaires to those incarcerated, asking them to choose between Japan and America.

The tumultuous events led to what Susan Kamei, a USC lecturer in history, called “hyperassimilation,” as many Japanese Americans sought to distance themselves from Japan and prove their American bona fides.

Activities that immigrant parents had pushed on their second-generation Nisei children — Japanese language school, dance, martial arts — largely fell by the wayside in subsequent generations.

As the wartime trauma has faded over time, however, the two communities are reweaving those frayed connections.

Yasuko Takezawa, a professor at Kyoto University and expert in Japanese American studies, said that recently there have been a number of TV documentaries and dramas focusing on the incarceration and Japanese American soldiers during WWII.

She said the Japanese American wartime experience can help inform the Japanese about the consequences of war and treatment of their own minorities in Japan, especially when international tensions arise between countries.

On Saturday, both the Japanese Chamber of Commerce of Northern California and the Japan Business Assn. of Southern California sent tour buses to Manzanar with nearly 80 representatives of leading Japanese corporations.

One of them was Kiichi Nakajima, vice president and Southwest regional manager of Japan Airlines Co. in Los Angeles. Nakajima said he had never learned about the incarceration growing up in Japan and was shocked by it.

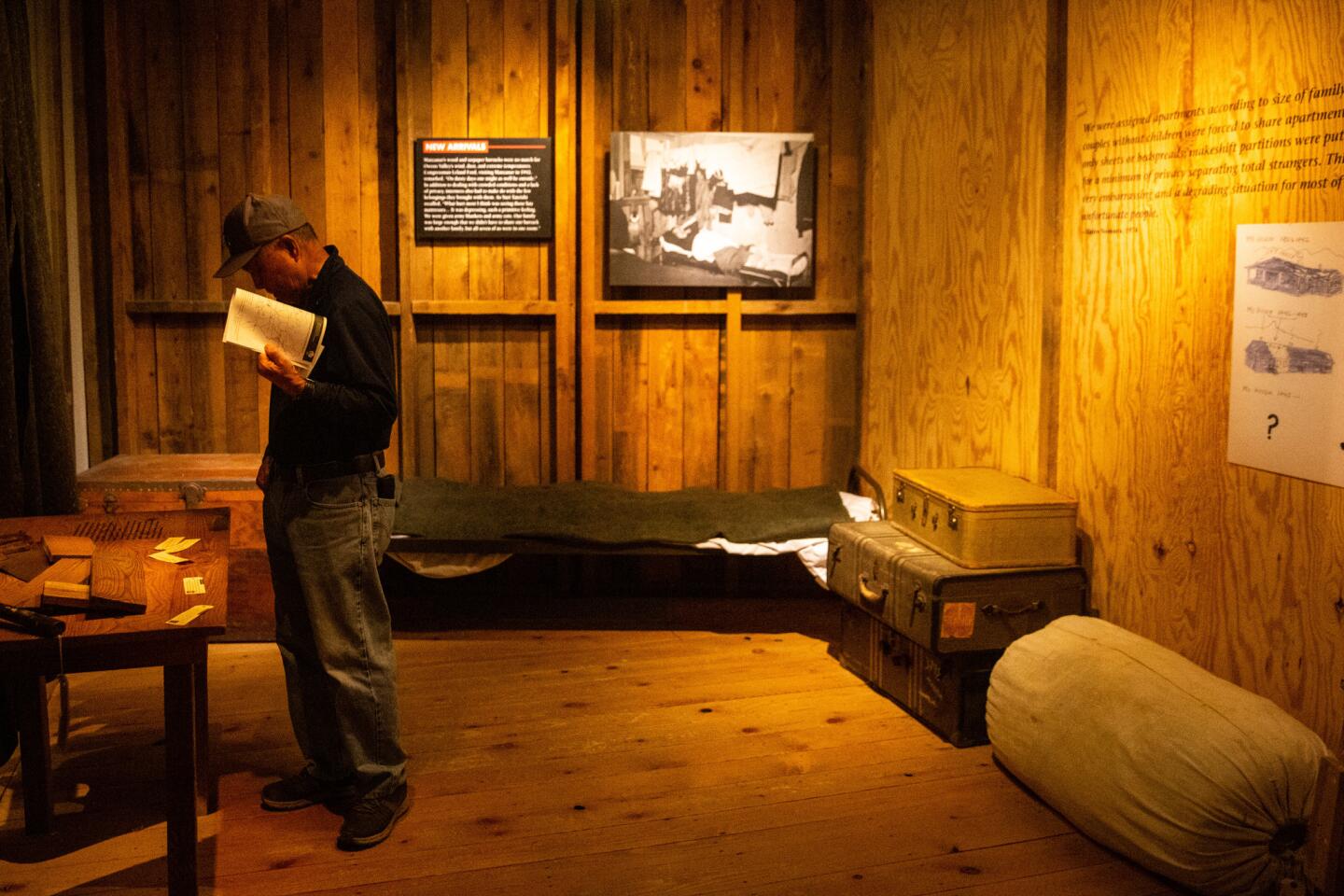

As he examined exhibits in the Manzanar National Historic Site’s visitor center, he said he was most moved by an illustration of young men in camp beating up another during a Manzanar riot.

“A lot of people must have had so much stress,” he said. “It is very sad and painful for me.”

Shimpei Ishii, deputy director of the nonprofit Japan Foundation, marveled at photos of Japanese workers who transformed the desert into fertile fields of vegetables and flowers. They even created a Japanese garden with a pond and bridge. How they pursued daily life under such hardship, he said, was deeply touching.

Toshihide Kotake, an executive with a Japan-based travel agency who heads the Japan Business Assn.’s downtown committee, said his group plans to promote more events to strengthen ties with Japanese Americans.

Miki said her “secret hope” is that the corporate leaders will raise their awareness of social justice and take it back to Japan to “change the future and make the world a better place.”

As the day drew to a close, bearers of banners for each of the 10 camps led a procession to the former cemetery. There, against the dramatic backdrop of the snow-capped Sierra Nevada, ministers of various faiths offered blessing, chants and prayers before Manzanar’s white concrete obelisk inscribed with black ideographs, “Monument to Console the Souls of the Dead.”

Afterward, Muslims rolled out rugs for afternoon prayers and pilgrims laid flowers around the monument.

Noburo Kamibayashi sat beneath a tent, taking it all in.

The Santa Monica resident, 89, was one of the few people in the crowd who actually had been incarcerated at Manzanar. He was only 11 when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and recalls going to school the next day and friends shunning him as talk spread about “getting those Japs.”

He remembers packing up his marbles, leaving behind his bicycle and his dog, Poochie. At Manzanar, he recalls the blazing sun, the choking dust and fierce windstorms.

His family chose to return to Japan to care for his ailing grandmother. But Kamibayashi found himself bullied by boys who teased him because he couldn’t speak Japanese well.

He dropped out of school and helped his family farm rice, but Japan’s devastating post-war poverty prompted him to return to Los Angeles alone at age 17.

He started gardening and doing odd jobs to send products back to Japan — lipstick and saccharine — that his family could sell.

He served in the U.S. military during the Korean War. He eventually went to trade school, got a job at an aerospace firm, married his wife, Lily, and had three children.

But Kamibayashi said he doesn’t dwell on his hardships. “I kind of put it behind me and try to look forward,” he said.

In fact, he said, he only came to the pilgrimage because his daughter, Judy Louff, insisted.

“If I come up this way, I’d rather go trout fishing,” he said.

Follow @teresawatanabe on Twitter

teresa.watanabe@latimes.com

Twitter: @teresawatanabe

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.