Bromberg’s employee has seen Alabama jewelry store, owners through 75 years

Frances Moore worked for Bromberg & Co. for more than 75 years. “Miz Frances” shared a special bond with the store owner, Ricky Bromberg. She died over the weekend at age 94.

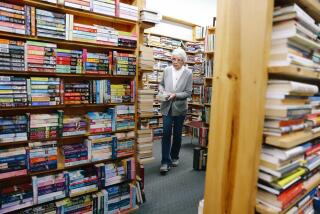

She walks with a cane now, the petite white-haired woman who has meant so much for so long in Ricky Bromberg’s life.

“Can I take your purse?” he asks as Frances Moore eases into the jewelry store his family has owned for six generations. “You hold on to that handrail now.”

His voice is tender, like he’s guiding a fragile favorite aunt. Moore isn’t exactly family, at least not technically. Now 93, she has worked for the Bromberg family business for 75 years, longer than anyone else — employee or family.

Known here as simply Miz Frances, the quiet African American woman with a penchant for bright colors had already worked two decades at the business before Bromberg was even born.

Years later, she took a liking to the quiet child who ran up and down the spiral staircase in his grandfather’s flagship store in nearby Birmingham. Without children of her own, she called him “my little boy.”

Now 55, Bromberg is president of the firm his grandfather’s great-grandfather founded in 1836. Married, with his own touch of gray and a son out of college, Bromberg has seen his life tick away like the Rolex watches he sells from behind reinforced glass.

Yet one habit remains, one facet of years gone by. Miz Frances still shows up for work. Just like always.

“They say I’m stubborn,” she said. “But when you stop and think about it, I’m just old.”

It’s a tale of longevity and dedication, true, but it’s also a story of how, in a city once infamous for its racial divide, Miz Frances and the Bromberg family found a way to transcend class and race.

“Frances is a living history, an emotional connection to the past,” Bromberg said. “She is simply one very special woman.”

Moore started at Bromberg & Co. in 1939, when America still reeled from the Great Depression. Bread was 8 cents a loaf and “Gone with the Wind” and “The Wizard of Oz” were packing theaters.

At 18, she dreamed of attending college, but with a struggling family of 10, her parents said the girl they called Frankie had to go to work. Her father, Aaron Wills, who worked for the Brombergs as janitor and deliveryman, told his daughter to show up at the store one day.

“He said, ‘Go down to Bromberg’s and tell them who you are,’” she recalled.

She began stocking silverware and earned $8 a week. Each day after work her father urged caution, offering advice on how to be a good worker.

“I said, ‘Daddy, I know how to do this.’ And he said, ‘I’m trying to help you keep your job.’” Her father always had advice — about work or how she spent her money. He’d say, “Listen, I’ve already been down that road myself.”

At work, Frank Bromberg Sr. was often a taskmaster who cussed when he felt people weren’t working hard enough. “I know what you’re doing here,” he’d say in the high-pitched squeak of actor Walter Brennan. “You’re working like hell to stay out of work.”

But he always liked Miz Frances — her parents made sure of that: “At dinner, they’d say, ‘Work hard. You can steal in more ways than one: You can steal time.’”

World War II and the Korean War came and went. After ugly years of Jim Crow, African Americans marched in Birmingham for equal rights in the 1960s, as police wielded batons and water cannons. All along, Miz Frances felt at home at Bromberg’s, where everyone used their first names.

Over time, she wrapped gifts, arranged flowers, checked inventory — whatever she was asked to do.

Once, a vendor claimed Miz Frances had shorted a package. But the store stood behind her: “They said, ‘If Miz Frances said she put it in there; she put it in there.’ And that was that.”

Later, Frank Sr.’s brother, William Bromberg, summoned her to his office: He’d dropped a loose diamond and wanted her to find it. His trust was obvious. Miz Frances asked male employees to check the cuffs in their pants before the stone was found near the display where it had gone missing.

By 1968, a young Ricky Bromberg was racing around the store. The other day, as Moore and her longtime employer sat in a stockroom, she looked at him and smiled.

“He’s like his grandfather, but he doesn’t cuss like his grandfather,” she says. “I used to think he was a tattle-tale, that he ran up those winding stairs to tell his grandfather everything.”

Bromberg leans back in his swivel chair, blushing: “That’s not true.”

Moore’s parents were dead by 1971. She married twice and lost both husbands. She recalls: “One day, Ricky’s father told me, ‘Miz Frances, don’t marry no more: You’re snakebit.’”

More years passed. Ricky Bromberg’s grandfather died; his father, Frank Jr., retired. He took over the business. When Miz Frances could no longer drive and couldn’t find a ride, he arranged for transportation, or did the job himself. Then, at 89, Moore fell at the store and broke her hip. Bromberg rushed her to the hospital.

He stepped outside the emergency waiting room to take a phone call as a doctor arrived to see her. He asked how she’d fallen.

She told him she had been at work. “He thought I was out of my head,” she says. “I told him to just wait, the boss man will be right back.”

Eventually, Moore’s knees gave out. She got a hearing aid. Since she started, more than a dozen presidents have served in office, the U.S. has fought several wars, and a new century has dawned. More than once, she tried to retire, feeling guilty for taking a job she thought could go to a young person. After she’d been gone awhile, Bromberg telephoned, imploring her to return.

The two shared a bond — even a birthday. She reminded him of the long-gone days when his beloved grandfather was at the helm. Again, he asked her to return. He missed her.

“I don’t even know how to use a computer,” she said.

It was all right, he assured her. Just come back.

And so she did. But they made a deal: She’d only come in when she felt up to it, doing clerical work in the back office. And when the work is done, she goes home.

In November, on the 75th anniversary of her hiring day, Bromberg threw Miz Frances a surprise breakfast, inviting many of her extended family.

She sent a thank-you card, saying something the two have always suspected. She wrote in a clear steady hand: “You might have added a few years to my life.”

The other day, when it was time to go, Bromberg escorted his most loyal employee to the door.

No one said it, but they knew: Miz Frances would be back. As long as there was work to do.

Twitter: @jglionna

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.