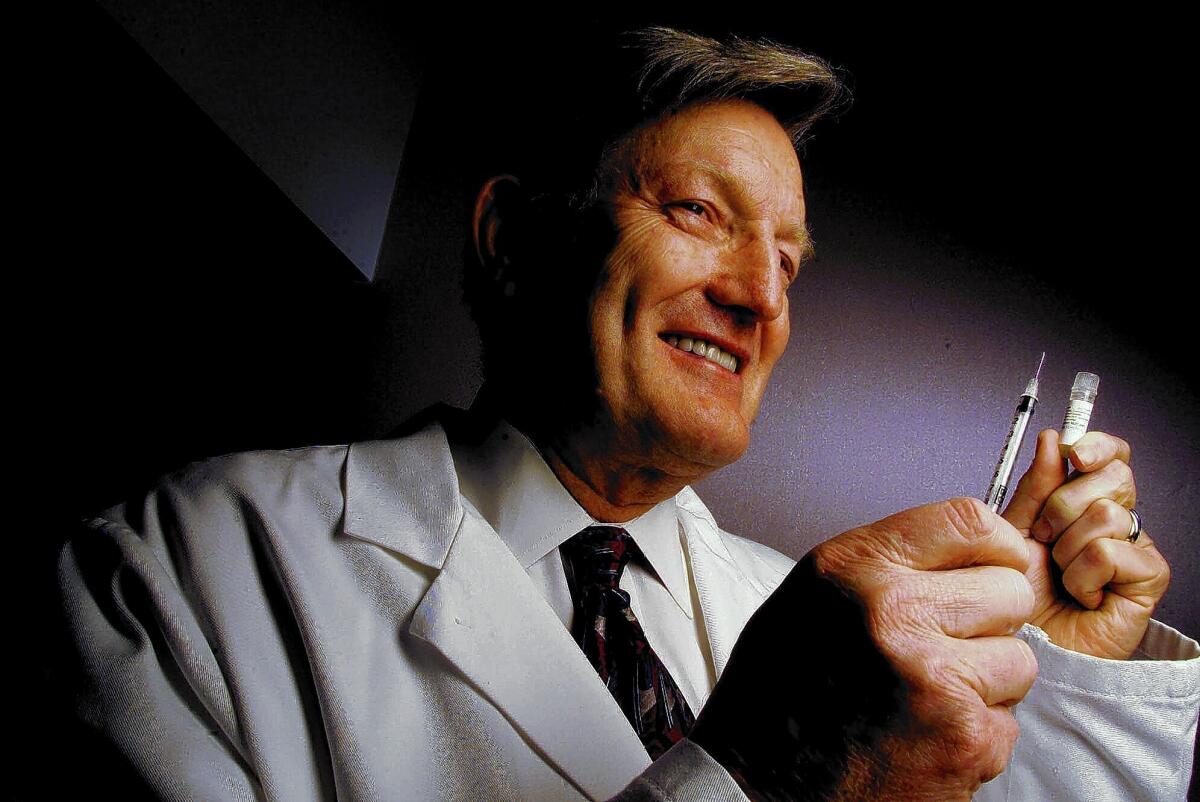

Donald Morton dies at 79; renowned cancer surgeon and researcher

Certain types of cancer, particularly melanoma and breast cancer, metastasize by shedding malignant cells into the body’s lymph system, where they travel to nearby lymph nodes and form new colonies. From there, the cells can spread to other organs, ultimately involving large areas of the body.

Until about 30 years ago, physicians surgically treating breast tumors in advanced stages would remove many nearby lymph nodes in an effort to forestall such spread. That could involve removing 20 to 40 lymph glands in the axillary lymph system under the armpits, a procedure that in itself could produce many adverse effects, including fluid retention and tissue swelling.

Moreover, microscopic analyses indicated that as many as 80% of the removed nodes had not been infiltrated by tumor cells.

In the 1970s, Dr. Donald Morton, then at UCLA’s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, reasoned that before cells could spread to many lymph nodes, they must first pass through the lymph node nearest to the tumor, which he called the sentinel lymph node. He developed a technique for injecting a dye — and later radioactive tracers — into the tumor and identifying the first lymph node it reached.

This lymph node could be surgically removed during the same operation that removed the tumor and examined for traces of cancer cells. If no malignant cells are present, there is a very high probability that the cells have not migrated to other lymph nodes and no further surgery will be necessary.

If malignant cells are identified, however, then other lymph nodes can be removed.

This procedure not only allows time for a more careful and thorough examination of the sentinel lymph node, but it also prevents large numbers of unnecessary surgeries. By some estimates, the use of sentinel lymph node evaluation saves the U.S. healthcare system more than $3.8 billion per year in the treatment of melanoma and breast cancer.

Morton, who also spent more than four decades attempting to develop a therapeutic vaccine for melanoma, died of heart failure Jan. 10 at Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica. He was 79.

“Don Morton was one of the most famous cancer surgeons in the world and was instrumental in changing the face of cancer and cancer research,” said Dr. Anton J. Bilchik, chief of medicine at the John Wayne Cancer Institute at Saint John’s, where Morton spent the last 23 years of his career. “His contributions have been monumental, literally saving countless lives.”

In a 2011 editorial in the Journal of Surgical Oncology, Dr. Charles M. Balch of Johns Hopkins University wrote that “Donald Morton is truly a legend in surgical oncology, an icon as a surgical investigator, a pioneer in melanoma, a valued mentor, an authentic role model and a cherished friend….”

Donald Lee Morton was born Sept. 12, 1934, in the small coal-mining town of Richwood, W.Va., and grew up in poverty. He enrolled at Berea College in Kentucky, which provided free enrollment to disadvantaged students. He completed his undergraduate education at UC Berkeley in 1955, then received his medical degree from UC San Francisco in 1958.

“For me,” Morton once said, “I think the greatest accomplishment was making it from rural West Virginia to the Westside of Los Angeles. I grew up during the Depression in a house that my dad built. We had no running water, no indoor plumbing and no electricity.”

After a fellowship at the National Institutes of Health, Morton joined UCLA, where he rose to become chief of general surgery and chief of the division of oncology. One of his patients was John Wayne, who died in 1979 after a long battle with cancer. With Wayne’s family, Morton established the John Wayne Cancer Clinic at UCLA in 1981.

Ten years later, seeking more space, Morton and some of his associates moved to Saint John’s, establishing the John Wayne Cancer Institute there.

Early on, Morton developed an interest in melanoma, the most lethal form of skin cancer. Believed to be caused by sun exposure, melanoma has been increasing in incidence for three decades. This year, an estimated 76,000 new cases will be diagnosed in the United States, according to the American Cancer Society, and about 9,500 people will die from it.

Researchers had observed that — rarely, perhaps once in every 2,000 to 5,000 melanoma cases — the cancer would regress spontaneously. Frequently, this occurred after an unrelated bacterial infection. Morton reasoned that the body’s immune system could fight off a melanoma if it could be stimulated to attack.

Initially, he hoped to take tumor cells from a patient, irradiate them so they could no longer replicate, and inject them back in the body to provoke an immune response. That immune response would be accelerated by injecting a weakened bovine tuberculosis bacterium known as bacille Calmette-Guerin, or BCG, which has long been used as a tuberculosis vaccine.

University officials were reluctant for him to inject the tumor cells, however, so he began by injecting BCG directly into tumors. In many cases, it appeared that the tumors regressed and were destroyed.

Eventually, Morton developed three separate lines of melanoma cells that displayed the most common antigens, or surface proteins, found in human tumors. The three types of cells were combined with BCG in a therapeutic vaccine called Canvaxin, which seemed to prolong lives in early trials at Saint John’s.

The National Cancer Institute funded early trials of the vaccine, which appeared promising, but researchers were concerned that the vaccine may have been given to patients who were most likely to survive. In 1998, Morton founded the private company CancerVax to obtain sufficient funds for much larger trials at other institutions.

Those trials were abandoned in 2005 when an independent data review committee concluded that the vaccine did not produce lengthened survival. CancerVax subsequently merged with the German company Micromet, which was then purchased by Amgen of Thousand Oaks.

In 1989, Morton noticed a mole on his abdomen that turned out to be melanoma. It was caught early, however, and successfully removed surgically. He did not take his own vaccine. “If the chance of a cure is 90% with surgery,” he told the New York Times, “why would I even want to give myself an experimental vaccine?”

Morton co-wrote more than 1,000 research papers and received numerous scientific awards.

His first wife, the former Wilma Miley, died in a car accident in 1982. He is survived by his second wife, Lorraine, whom he married in 1989; daughters Danielle Morton, Christin Kazmierczak, Laura Morton Rowe and Diana Morton McAlpine; son Donald L. Morton Jr.; eight grandchildren; a brother, Patrick; and a sister, Carolyn Morton Karr.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.