Commentary: My wife and I navigated IVF just fine without the Alabama Supreme Court

I never thought of myself as a mass killer, but the Alabama Supreme Court has a different idea.

Last month, the court ruled frozen embryos are legally children, allowing several in-vitro fertilization patients to sue a fertility clinic for wrongful death over the inadvertent destruction of their refrigerated, um, kids.

In a Bible-infused ruling, Alabama’s Supreme Court has held — dangerously and preposterously — that frozen embryos are ‘children.’

To be clear, you cannot freeze a child and thaw it later unharmed. An embryo, which can be frozen, is not a microscopic child; rather, it is a small collection of cells that develops after a sperm and an egg combine. People undergoing in-vitro fertilization, or IVF, try to produce as many embryos as possible outside the body and transfer the best of the batch in-utero to increase the chance of a successful birth.

That often results in unused embryos being frozen for later use or eventually discarded or donated.

Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which reversed abortion rights under Roe vs. Wade, laid the groundwork for further denial of individual liberty on religious grounds.

I know this because 13 years ago, my wife and I underwent fertility treatment, a months-long process that, in hindsight, previewed the highs and lows of parenthood by putting us through an emotional and financial wringer. We failed multiple conservative treatments before my wife opted for IVF, a therapy that essentially took over her life for an entire summer, with no guarantee that it would work.

Looking back at our experience, I dread the thought of would-be parents in Alabama enduring a similar ordeal but under the patriarchal eyes of their Supreme Court justices. Already, several Alabama fertility clinics have suspended IVF since the Feb. 16 ruling; I wonder about the various stages of treatment in which these patients were left in the worst kind of lurch.

Some states exempt fertility care from abortion bans. But what does that mean for bodily autonomy?

Some were probably a week or two into the daily hormone injections that hyper-stimulate egg growth, swelling ovaries to the size of baked potatoes. Others might have finished the hormones and were ready to have eggs harvested. Perhaps some had just undergone a surgery recommended by their doctor to improve their chance of becoming pregnant.

In short, IVF is really an exquisitely timed, modern-medicine dance of tests, appointments, treatments and adjustments to those treatments. Injections must be given on time, whether you’re at home or at work, sitting on your couch or in your car. You don’t just pause for several days and pick up where you left off, so the fact that the Alabama Legislature passed a bill this week protecting IVF doesn’t help these patients. If you stop, you start all over again.

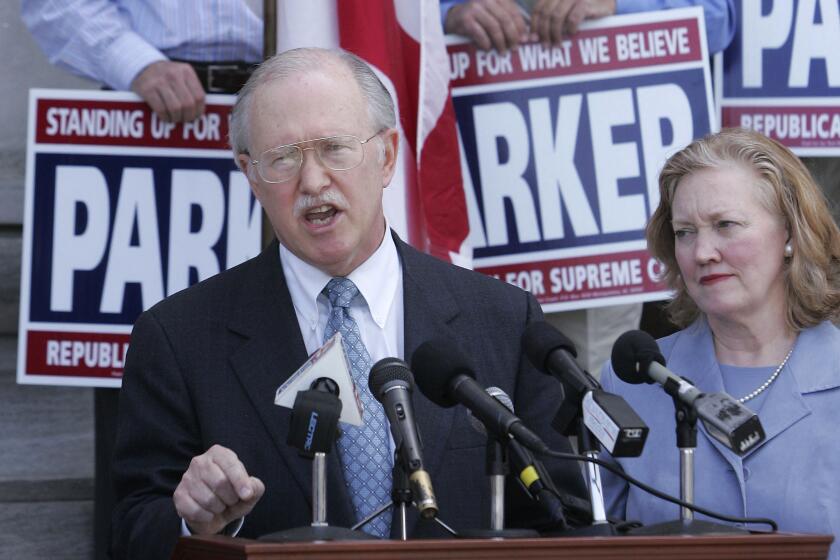

But according to Alabama Chief Justice Tom Parker, whose concurring opinion in the case has raised alarms for its Gileadean “wrath of a holy God” verbiage, fertility doctors and IVF patients have little to worry about. To him this is all much ado about nothing, because developments in fertility care outside the U.S. obviate the need to create (and possibly destroy) multiple embryos for a patient.

Reading this portion of his opinion, Parker struck me as willfully misrepresenting his cited sources or just being grossly unfamiliar with the practice of IVF. For example, he noted that the guidelines of the Fertility Society of Australia and New Zealand “dictate that physicians usually make only one embryo at a time.” I found the guidelines, and they say no such thing.

They do, however, discourage transferring more than one embryo at a time, because pregnancies involving twins and triplets pose additional risk to the patient. Perhaps Parker confuses the embryo’s “sanctity of life” with the mother’s safety, a telling mistake on his part. But there should be no confusion: Doctors transfer fewer embryos to reduce risk to the patient, not to avoid killing unborn children.

Here, too, I have some experience. Before embryo transfer, my wife and I had to decide whether to use one or two. We had upward of 10 to choose from — more than most patients our age, we were told — but none of our embryos was graded in the highest-quality tier. Fully informed by our doctor of the possible risks of a twin pregnancy (it also helped that my mother was a highly regarded obstetrics nurse), we transferred two embryos.

We and our doctor had total freedom to make these choices, guided solely by our wishes and my wife’s safety, and the ability to make as many embryos as possible prior to transplantation. The creation of multiple embryos, it seems, is often a necessary byproduct of good IVF care.

How did it all end up for us? My wife’s pregnancy ended precisely 12 years ago today, with the birth of our twins. Happy birthday, boys.

I hadn’t given any thought to our unused embryos until recently. Now I joke with my wife about our freezer babysitting for us in a pinch.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.