Study: Emergency room closures can be deadly for area’s residents

It stands to reason that when a hospital emergency room closes, people in the surrounding neighborhood suffer. But how much? A new study quantifies the impact in California, finding that patients affected by ER closures were 5% more likely to die after being admitted to a hospital than were patients who didn’t lose an ER in their neighborhood.

The authors of the study, published Monday in the journal Health Affairs, couldn’t say exactly how the disappearance of emergency rooms translated into higher mortality for hospital patients. Fewer ERs leads to longer wait times for treatment. It also means patients have to travel farther to get emergency room care, and it may prompt some to simply stay home. All of these factors force patients to wait longer – and perhaps get sicker – by the time they are admitted to a hospital.

Understanding the implications of ER closures is important, since they have been disappearing for years. The number of hospital emergency departments in the United States fell from 4,884 in 1996 to 4,594 in 2009, a 6% decline. Meanwhile, the number of patient visits increased from 90 million to 136 million, a 51% increase. Figures like these prompted the Institute of Medicine to declare that emergency departments were “at the breaking point” back in 2006.

For the new study, a trio of researchers from Harvard Medical School, UC San Francisco and the Ecologic Institute in San Mateo, Calif., examined data from the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development to see how many hospital emergency rooms were in operation and what happened to the patients they treated.

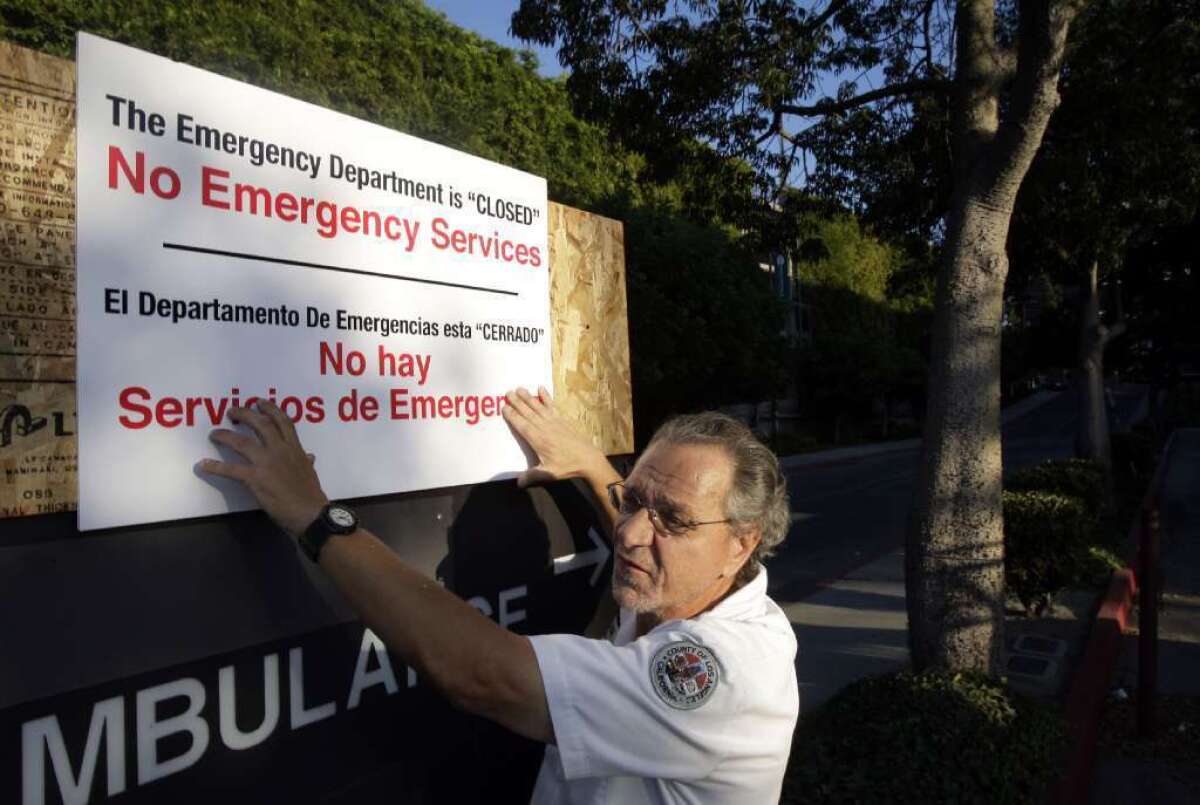

From 1999 to 2010, 26 California hospitals that had emergency rooms shut down, and another 22 closed their emergency rooms but remained open, according to the study. Each of those 48 hospitals affected a geographic area that the researchers defined by the ZIP codes of the patients who used the facilities.

During the years studied, more than 16 million patients who visited California ERs were admitted to the hospital. A whopping 25% of them were from neighborhoods affected by an ER closure, and 75% were not. (Emergency rooms are required by law to treat all comers regardless of how sick they are or whether they can pay for their care.)

Overall, patients who were African American, Latino, women or adults under the age of 65 were more likely to have suffered the loss of an ER in their community, the researchers found. So were patients who were uninsured or were covered by Medicaid, the federal insurance program for low-income Americans.

The impact of ER closures was greatest on non-elderly adults (those between the ages of 18 and 64). Among patients in that age group, those who lived in an affected area were 10% more likely to die after being admitted to the hospital compared with patients who didn’t lose an ER.

Elderly patients (those 65 and older) appeared more likely to die after being admitted to a hospital if they were from an affected area, but the difference wasn’t large enough to be statistically significant.

When the researchers focused on patients from neighborhoods that lost an ER within the previous two years, they found that affected patients were 4% more likely to die during their hospital stay than were patients who hadn’t lost an ER so recently.

The study authors also did a separate analysis of patients who went to an ER because they were suffering from a time-sensitive medical emergency. Among heart attack patients, for example, those who were from a region that lost an ER were 15% more likely to die in the hospital; among patients who had a stroke, those affected by an ER closure were 10% more likely to die in the hospital; and among patients suffering from a life-threatening infection causing sepsis, those who lost an ER in their community were 8% more likely to die after being admitted to the hospital.

Losing an emergency department did not increase the risk of near-term death for patients who went to an ER seeking treatment for asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the researchers found.

Overall, the researchers found nothing good about the disappearance of hospital emergency departments, or EDs.

“Disproportionate numbers of ED closures may be driving up inpatient mortality in communities and hospitals with more minority, Medicaid and low-income patients,” they concluded. “Our findings regarding the ripple effect of closures on surrounding communities suggest that it may be time to reassess the extent to which market forces are allowed to dictate ED closures and access.”

For more medical news, follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan and “like” Los Angeles Times Science & Health on Facebook.