Surgery to remove wisdom teeth puts some teens and young adults on a path to opioid abuse

For older teens and young adults, the extraction of so-called wisdom teeth is a painful rite of passage. A new study suggests it’s likely made more perilous by the package of narcotic pain pills that patients frequently carry home after undergoing the common surgical procedure.

The study offers fresh evidence of how readily — and innocently — a potentially fatal addiction to opioids can take hold. It also underscores how important it is that dentists rethink their approach to treating their patients’ postoperative discomfort.

In a group of close to 15,000 people whose first-ever prescription for opioid painkillers came from a dentist or dental surgeon, researchers found that about 7% filled another opioid prescription 90 to 365 days later.

And in the year following their dental procedure, close to 6% of patients who left their dentist’s office with a prescription for opioids had a “health care encounter” — a hospitalization or trip to the emergency room, a physician consultation, or a session with an addiction specialist — in which a diagnosis of opioid abuse was documented.

That’s well over 10 times the rate at which a comparison group of patients who did not receive a prescription for opioid painkillers got that diagnosis. Patients in both groups were 16 to 25 years old, and all were treated by dentists during 2015. Researchers then were able to track the patients for at least a year.

Compared with the study’s boys and young men, girls and young women were more likely to continue using narcotic pain relievers after getting their wisdom teeth out, and they were much more likely to abuse the drugs.

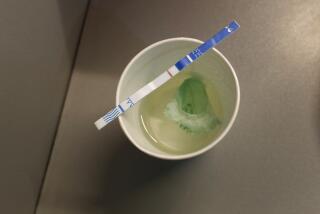

The typical prescription capable of setting such havoc into motion was a pack of about 20 pills of an opioid narcotic such as OxyContin, Vicodin or Percocet.

Published this week in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine, the new research comes at a time when opioid drugs are claiming the lives of 115 Americans a day. Although those fatalities are also caused by street drugs such as heroin and, increasingly, synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, as many as 4 in 5 of those addicted to heroin say they started by abusing medications that were prescribed for legitimate purposes.

That in turn has shined a light on the medical profession’s prescribing practices and its role in the public health crisis. In 2016, as the epidemic of overdose deaths continued its steep rise, those in the medical and dental professions prescribed enough painkillers to medicate every American daily for close to a month.

Although many of those pills are prescribed to manage the agony of patients with excruciating pain conditions, physicians and dentists still prescribe opioids to patients whose pain could be treated more safely, and just as effectively, with nonnarcotic drugs.

The new study also calls into question the wisdom of routinely extracting those pesky molars that tend to push through our rear-most gums in late adolescence or early adulthood, often crowding other teeth or becoming impacted.

Study author Dr. Alan R. Schroeder, a Stanford University pediatrician with an interest in “safely doing less,” said the benefits of wisdom tooth extraction have not been rigorously studied or demonstrated. Nor, he added, have its risks.

Studying the risk of opioid addiction or abuse, at least, seemed a good place to start, he said.

The surgical removal of wisdom teeth comes with such potential downsides as dry sockets, gum pain and nerve damage, as well as risks associated with the anesthesia used during those procedures.

And then there are the drugs. Dental surgeons have been among the most liberal prescribers of opioid painkillers, and they’re also heavy prescribers of antibiotics. Those medications can come with side effects of their own, and over-prescription is believed to foster the rise of antibiotic-resistant infections in populations.

Indeed, Schroeder said, the dearth of research about wisdom tooth extraction makes its frequency hard to judge. And that, in turn, forced Schroeder and his coauthors to make a key assumption in their study.

Dental insurance databases are scarce and many wisdom tooth extractions are paid for out of pocket. But given the age of most of the patients leaving a dentist’s office with an opioid prescription, Schroeder and his coauthors figured the most likely cause was wisdom tooth surgery (a third-molar extraction in dental parlance). The authors’ conclusion that opiate abuse is a possible risk of wisdom tooth removal rests on this assumption.

But when you consider how many young people have their wisdom teeth removed, and how routinely dentists send their patients home with a prescription for narcotic pain relief, the implications are pretty alarming.

An unpublished 1999 study by the American Dental Assn. and cited by the authors estimated that about 5 million such extractions are performed per year. By 2009, another study had concluded that dentists were the leading source of opioid prescriptions for children and adolescents ages 10 to 19, accounting for close to one-third of opioid prescriptions in this age group.

The American Dental Assn., meanwhile, has vowed that its members will reduce their opioid prescribing. In a statement released in March, then-president Dr. Joseph P. Crowley called on dentists to “double down on their efforts” to write fewer prescriptions of opioids for dental pain, to lower the doses that are prescribed, and to shorten the duration of prescriptions — all measures known to reduce addiction risk. The association has also backed state legislation to limit opioid prescriptions’ dosage and duration, and to track medical professionals’ prescribing practices.

“The dental profession deserves credit for trying to tackle this,” Schroeder said. “It’s easy to point the finger at dentists — over time, they have contributed a fair amount of the opioid exposure. But they really have made efforts to limit that in recent years.”

MORE IN SCIENCE