On tiny Guernsey, history, literature and art loom large

The Germans thought they were seeing military vehicles at St. Peter Port on Guernsey, an island in the English Channel just 30 miles from Normandy, France. They took to the skies and on June 28, 1940, rained hellfire on a place that had been demilitarized. Thirty-four islanders were killed.

The vehicles were carrying tomatoes.

Two days later, 15,000 German troops landed and occupied the island without resistance. A week earlier 17,000 islanders, mainly children, had been evacuated on 70 Dutch cattle transport boats.

The 25,000 islanders who remained spent the next five years hiding, scavenging, starving. Visiting here now, it is hard to believe that the occupation nearly killed gentle Guernsey.

Neutral territory

Until 1204, Guernsey and the neighboring islands of Alderney, Sark and Herm were intertwined with French politics. But several French invasions, the English civil wars, state-sponsored piracy and other threats led to Guernsey’s neutrality.

The four small islands constitute the Bailiwick of Guernsey, home to about 63,000 residents. Guernsey is self-governing and has its own currency, legal system and advantageous tax laws; it is not part of Britain or the European Union.

I visited Guernsey in November, drawn by its wartime history and “The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society.” The 2008 novel features Juliet Ashton, a free-spirited London writer who decides to visit the island after corresponding with several members of the society, a book club formed during the occupation.

I stayed at the Old Government House Hotel, affectionately called OGH, in the heart of hilly St. Peter Port. It was once the grand residence of the island’s lieutenant governor. Early in the German occupation, officers used it as military headquarters, but it then became a Soldatenheim — soldiers’ home — for the balance of the war.

Today, OGH’s buildings have been restored with art and period furnishings. Rooms and suites have been updated but maintain their sense of history and charm.

From my windows, I had a view of the harbor and 13th-century Castle Cornet, which played an integral role in protecting the island, housed anti-aircraft units in World War II and now holds museums and gardens.

Guide Gill Girard, a third-generation islander, walked me through St. Peter Port, stopping at the World War I monument in memory of the 1,110 fallen who were from the bailiwick. At the waterfront area called White Rock, a granite obelisk commemorates the island’s liberation on May 9, 1945. Several plaques memorialize the evacuees, deported Jews who died at Auschwitz, foreign workers, island deportees and bombing victims.

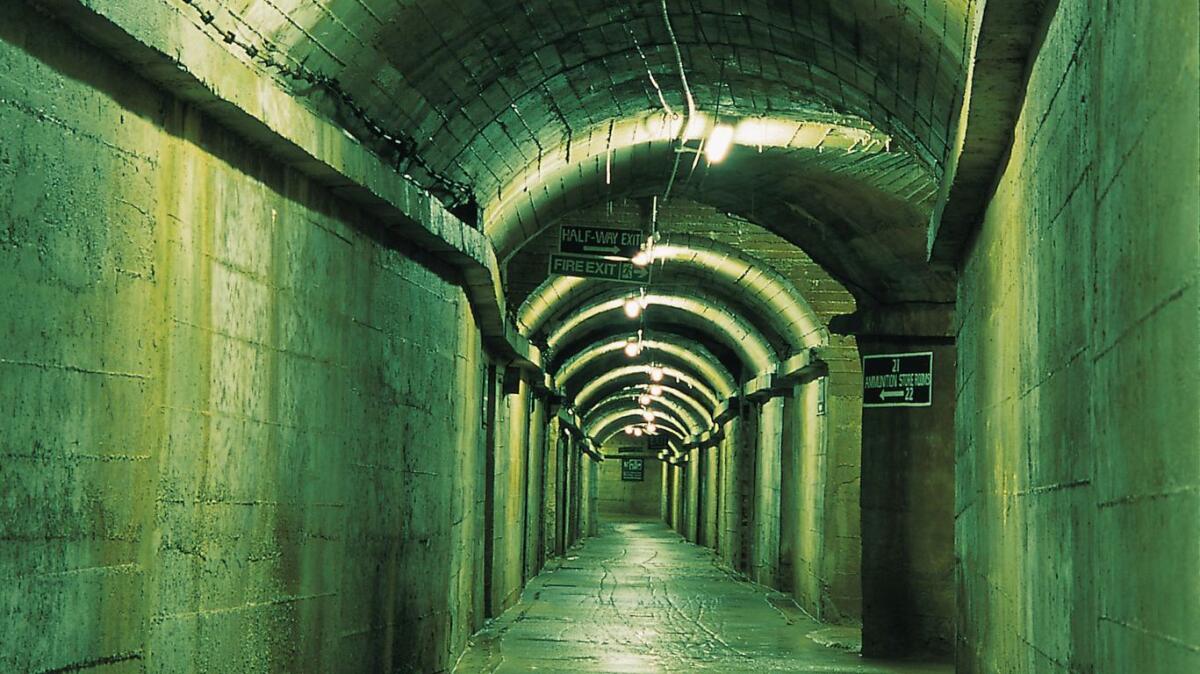

The German Underground Hospital is 10 minutes away in St. Andrew’s Parish, one of 10 parishes on the island. The underground space, excavated by slave labor over three years, is 75,000 square feet and is the largest structural reminder of the occupation. Between two damp, dreary corridors are remnants of its use as a hospital, with beds, equipment and rudimentary cooking facilities.

At the privately owned German Occupation Museum, Richard Heaume shares his vast collection of World War II memorabilia, including arms, uniforms, vehicles, motorcycles, photographs and evacuees’ suitcase contents. Two short films add context to this well-curated exhibition.

I later had tea with Molly Bihet, the 87-year-old author of several wartime books, including “A Child’s War.” Bihet was one of the few island children who did not evacuate.

She spoke of the occupation’s food deprivation, including finding “maggots in bread, collecting acorns” for her mother to grind for “coffee’” and “the meanness of some of the German officers.” The island “often felt like a huge prison,” but to this day she remembers “the many kindnesses of fellow islanders together striving to endure those years.”

Literary and artistic past

Guernsey’s natural beauty has long inspired literary and artistic creativity. In October 1855, Victor Hugo arrived in Guernsey with his two sons and mistress Juliette Drouet. His wife and daughter, both named Adèle, arrived later.

Hugo’s grand old villa, at 38 Hauteville in the hills of St. Peter Port, was his home for 15 years. It was closed for renovations when I was there but has recently reopened. From an adjacent property, Girard and I could see the villa’s massive gardens and the commanding sea view Hugo enjoyed.

Hugo started writing “Les Misérables” in France but completed it here. He also wrote “Toilers of the Sea” on Guernsey, heavily inspired by the island’s superstitions.

An imposing 21,000-pound limestone statue of Hugo, sculpted in 1913 by French artist Jean Boucher, is in Candie Gardens, home to the Guernsey Museum and about a five-minute walk from the center of St. Peter Port.

Moulin Huet Bay, with its craggy hills and sharply pointed rock formations, is farther south of St. Peter Port. Pierre-Auguste Renoir spent part of the summer of 1883 painting the bay, a stunning spot providing the ideal canvas to create. In all, Renoir completed 18 paintings of this picturesque place.

Then there is the “Potato Peel Pie Society.” You can easily visit, on foot or by car, several of the places mentioned in the novel. Society member Isola Pribby sold her “healthy” elixirs on Market Square. At the Little Chapel — a Lilliputian-sized edifice made of thousands of pieces of broken porcelain — Juliet Ashton comically noted that the priest “must have made his pastoral visits with a sledgehammer.”

The narrow, jade-green paths in St. Martin’s Parish include Gypsy Lane, where a group of islanders was confronted by German soldiers and the society was born. And there are numerous sea-view cliff walks intoxicating in their rugged beauty.

On my last night in Guernsey, I ate at the Crow’s Nest, the location of the Crown Hotel where Ashton met Dawsey Adams, her first Guernsey correspondent. The panoramic views of St. Peter Port from the restaurant’s enormous windows reminded me of Ashton’s Guernsey descriptions: “very beautiful in all its variety … wild cliffs, witches’ corners, Tudor houses and Norman stone cottages.”

Perhaps I will return one day, get stuck here in the fog and write another book — perhaps this time a love story with its genesis in peacetime.

If you go

THE BEST WAY TO GUERNSEY

From LAX, Norwegian offers nonstop service to London’s Gatwick Airport, and Delta offers connecting service (change of planes). Restricted round-trip airfare from $920, including taxes and fees. Aurigny and Flybe offer service to Guernsey from Gatwick and Heathrow, respectively.

Condor has passenger and car ferries from England’s south coast (Portsmouth and Poole) and from St. Malo in northwest France. Voyages take about three hours and start around $50 one way, per person. condorferries.co.uk

St. Peter Port is a walking city and that’s the best way to see it. The island has an excellent bus system with service to important sites, and a circle island trip (Bus 91 or 92) is only $1.30. Taxis are plentiful. For guided private, semi-private and group walking tours — including book clubs — of one to four days, Gill Girard is a wealth of local knowledge.

WHERE TO STAY

Old Government House Hotel & Spa, St. Ann’s Place, St. Peter Port, Guernsey; 011-44-0-1481-724-921. Gracious hotel with impeccable service. Doubles from $380, depending on room and season.

WHERE TO EAT

Crow’s Nest, Victoria Pier, Guernsey; 011-44-0-1481-728-994. Try the whole sea bream. Dinner for two $75.

Brasserie Restaurant at OGH. The fresh sea bass was outstanding. Dinner for two $100.

TO LEARN MORE

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.