Greece had long banned cremation — until the country ran out of room for bodies

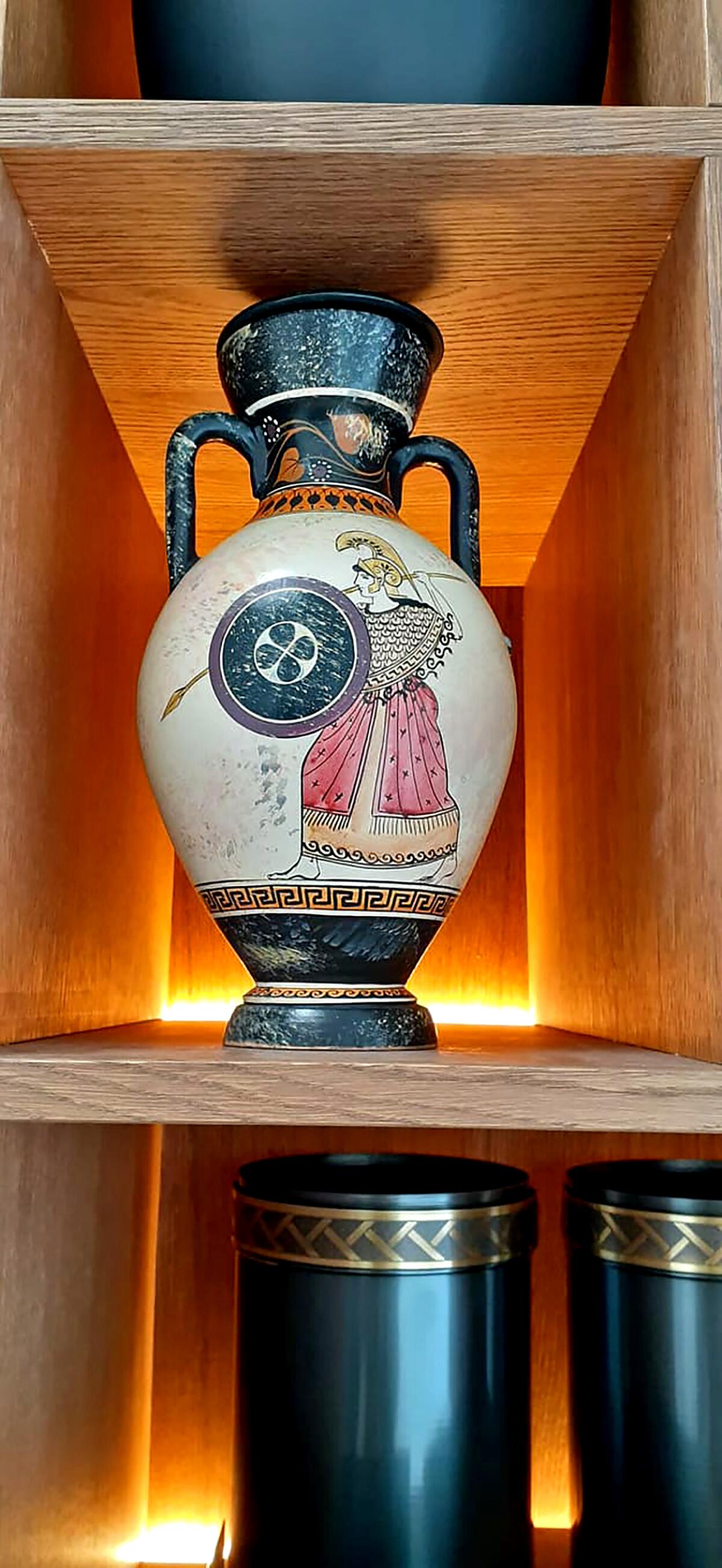

To show that cremation has long been part of the Greek way of life and death, Antonis Alakiotis proudly displays a wide range of funerary urns modeled on ancient Greek designs, available to house the ashes of your loved one for eternity. Prices start at $121.

“You will see that one as you walk through the entrance to the Archaeological Museum,” Alakiotis says as he walks with a visitor through the Ritsona Crematorium, the first and only such facility in Greece. Alakiotis, president of the Greek Cremation Society, is at pains to make clear the ancient Greek legacy of cremation, a custom as traditionally Greek as a church burial.

His sales pitch came just weeks after the first crematorium in modern-day Greece opened in late September, after decades of opposition from the country’s powerful Orthodox Church. Until then, Greece was the only country in modern-day continental Europe not to allow cremation. Those intent on turning a loved one’s remains into ashes needed to travel to neighboring Bulgaria, a costly and time-consuming process.

Although the Greek church teaches that cremation conflicts with teachings on resurrection, pressure to allow the practice mounted. Cemeteries in most urban areas have become increasingly overcrowded and have begun digging up remains after three years even though, in many cases, they have not fully decomposed. The remains are then stored above ground indefinitely in ossuary boxes.

Alakiotis was 14 when he had to watch his father’s body disinterred. In 1996 he promised a friend, a Greek Buddhist, that he would ensure his remains were cremated in Greece and to spare him the indignity of exhumation. The Greek Cremation Society was established a year later.

Alakiotis wasn’t able to fully fulfill his promise to his friend. When the friend died in 2004, his remains were transported to Bulgaria and cremated there. The ashes were brought back to Athens and scattered on a mountainside. But the experience spurred Alakiotis to keep lobbying.

Laws needed to be passed on a national level, and then municipal councilors needed to be lobbied and licenses acquired. One municipal council voted overwhelmingly in favor of building a facility, but weeks later the decision was overturned after a concerted campaign by the local bishop. Another municipality discovered that the land its cemetery was on didn’t belong to it and so it couldn’t issue a license to build a crematorium.

The adamant opposition of the church kept the stakes high and lawmakers aware of the political cost of defying it. Greeks are among the European Union’s most religious people, with an overwhelming majority baptized into the Greek church. In a 2018 study by Pew Research, 55% of Greeks said religion was very important in their lives, the highest percentage among the 34 European countries surveyed.

In the past five years, two national laws were passed permitting crematoria to be built outside of established cemeteries and allowing private companies, not just municipal authorities, to build them. That allowed Alakiotis to team with a construction company — Arsis SA — to create Crem Services SA and open the first crematorium in Greece. The Greek Cremation Society is a 30% shareholder in the operation.

On an average day, director Christos Tsakiridis, 39, says, four or five cremations are conducted. One recent Wednesday, there were 10, with family members and friends quietly gathered in small groups in the cafeteria over complimentary coffee.

“People want to farewell their loved ones with a semblance of dignity,” he says. “We’re providing the conditions for that.”

Alakiotis says there was a conscious decision to build the facility in Ritsona, almost 50 miles from Athens, to avoid what he calls any “unpleasantries” or protests.

The closest house is seven miles away, he says.

The single-story building is nestled among vineyards and at the edge of a private forest of pine trees. Mulberry, pomegranate and olive trees accompany the minimalist decor.

The business has created jobs for seven local people. There are plans to build similar facilities by the municipalities of Athens and Greece’s second-largest city, Thessaloniki.

The facility is now an option for both Orthodox and non-Orthodox Greeks as well as expatriates, from as far off as China, Germany or the U.K., where cremation is more common. Business has also come from as far as Cyprus, now the only European Union country where cremation isn’t available.

The church has redoubled its opposition. In a four-page leaflet issued by the Church of Greece’s Holy Synod, titled “Cremation: A Dignified Solution or Crude Recycling?” it outlines its arguments against cremation, describing how remains are crushed into dust rather than just burned, and the need for care to be taken of bodies awaiting resurrection. “Human bodies are not refuse!” it states.

What’s most significant, Alakiotis says, is that the average age of those being cremated is 75 — a demographic that one would assume would adhere more to the teachings of the church than younger generations. And it’s not cost that’s spurring Greeks to adopt cremation, Alakiotis says — it’s the custom of exhuming bodies after three years.

“Anyone who’s lived through that doesn’t want to subject their children to the same thing,” Alakiotis says. “The cost is important, but it’s not the biggest factor, not here.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.