Our coronavirus blind spot: People like me who need dialysis

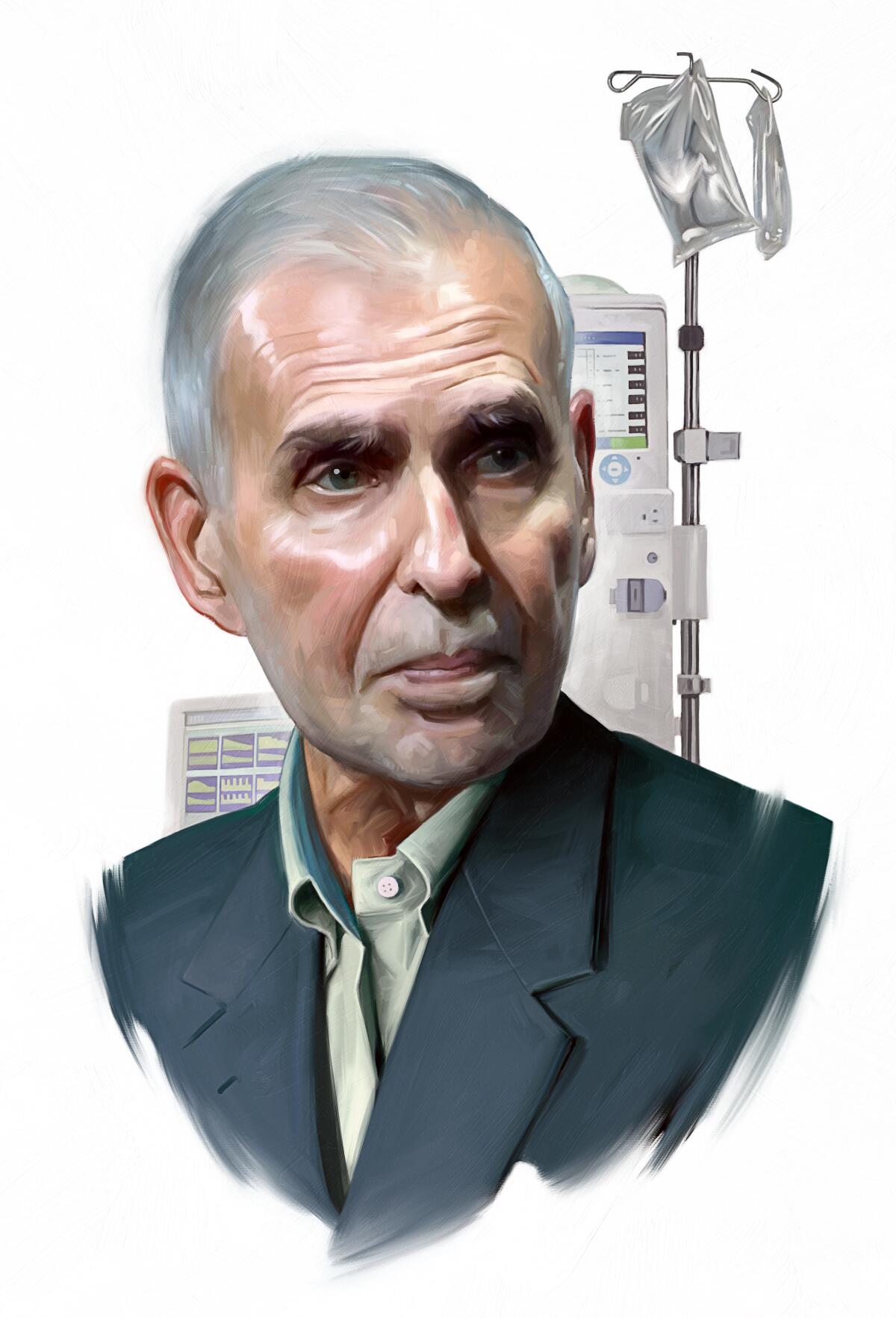

Today, at age 81, I am lying in a rehabilitation facility in Los Angeles. Several weeks ago I fell in my home, breaking my clavicle, several ribs and my hip, and began an intense regimen to regain my health. During this pandemic I am obviously concerned to be in a large healthcare setting, congregating with many people who have a weak physical constitution and are susceptible to contracting and spreading infection.

More than 30% of the early COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. as of March 16 were from a single nursing home — Life Care Center of Kirkland, Wash. Forty people in that nursing facility have died and more than two-thirds of their residents have been diagnosed with the coronavirus. We were shown the power of the virus to spread in such locations, and this has since spiraled: as of mid-April, 20% of all COVID-19 deaths in the United States were in nursing homes

Last month, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services administrator Seema Verma announced that all visitors were temporarily restricted from nursing homes. As CEO of Time Warner, when it was the largest media company in the world, I sat at the helm of 93,000 employees, amid constant interaction. Now I am required by federal regulations to sit here alone, and for good reason. This recipe of elderly, frail people in an enclosed communal environment is deadly.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also provided specific guidelines to address a similar deathtrap: dialysis centers, due to their comparable high volume of older patients (50% of all dialysis patients are over 65) and their history of infections are a very high risk for heightening the spread. More than 725,000 Americans suffer from kidney failure, otherwise known as end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Of these, at least 500,000 individuals are on dialysis.

Among the first two COVID-19 deaths in the U.S. were dialysis patients, and last month Fresenius, the largest dialysis provider in the US, disclosed its infection rate (less than 0.5% of its patients), which was nearly triple the per capita infection rate of the general population in the U.S. (0.17%) at the time. It is obvious — in both nursing homes and dialysis facilities — why bringing together frail and elderly patients in a bounded community during a pandemic is terrifying. With social distancing rules being impossible to observe in these treatment centers, we are likely to see more challenging containment situations.

Now imagine repeatedly cross-pollinating these vulnerable patients between two high-risk settings by taking nursing home residents to dialysis facilities several times per week and then bringing them back. Each trip exposes them to additional patients, staff and transportation workers. This could create nightmarish situations similar to Life Care Center of Kirkland across the nation.

Until recently, this would have been my fate. Like most patients on dialysis, I was traveling three times per week to an outpatient dialysis facility, exhausted for a full day in the aftermath and exposing myself to potential infections each time. Then I was privileged to begin home dialysis, and I now receive dialysis bedside in my rehabilitation facility. My exposure is only to my healthcare providers and I do not interact with any other patients. I am effectively quarantined, as someone in my current health should be.

Surprisingly, my treatment experience transformed for the better. I went from feeling like a slab of meat, thrown around anonymously in a clinic — one of the mega-dialysis duopoly’s 5,000 U.S. clinics — to a caring home treatment customized for my needs. This superior home treatment restored my vitality to such an extent that I joined Dialyze Direct, a progressive home dialysis company as Chief Mission Officer. My home dialysis experience has, on the whole, been dynamic and restorative.

However, my peers who remain traveling to and from the dialysis facility are having the opposite experience. Tens of thousands of elderly people will leave nursing homes and long-term care facilities today for a dialysis center where they will be exposed to other immunocompromised patients.

They will repeat this volatile but life-preserving tightrope walk a dozen more times this month. Even one case of coronavirus in this formula quickly snowballs into catastrophe. Every patient living in fear, pain or loneliness is a live human being needing help.

Receiving home dialysis treatments in a nursing home is not something that is only available to people like me (former CEOs). It could be provided to any patient who needs it. Unfortunately, right now it’s not available to many, which is mainly a function of the red tape and bureaucracy in healthcare. Our current system is characterized by slow decision making, limited willingness to try new and innovative therapies, and stubborn adherence to the status quo of where and how healthcare should be delivered.

President Trump signed an executive order last year that was meant to create new incentives to encourage in-home dialysis, and the Department of Health and Human Services has said it wants 80% of new ESRD patients either receiving dialysis in the home or getting a kidney transplant by 2025. I have praised the government’s landmark stance on home dialysis, but the current outbreak should not slow that down. It should accelerate it. The current providers are offering service at a higher cost and taxpayers are footing the $35 billion bill (which is 1% of the entire federal budget). Good thinking and compassion must prevail over the status quo now more than ever.

In just a matter of weeks, our country has shifted from focusing on productivity and ingenuity to a noble discussion about effective and moral distribution of resources to protect the lives of our citizens. We have so far risen to the occasion, accepting that there will be challenging consequences.

While there is much to do to suture our economy, our foremost priority has been preserving life. Many people with mild symptoms are heroically resisting the urge to go to emergency rooms to prevent the infection of healthcare workers. We are fighting our scarcity mentality at grocery stores to prevent supply chain issues. We have become makeshift home-schoolers of 30 million children to control this virus. We have all made principled sacrifices for the health of our broader community.

Many leaders in the private and public sector have given much sound advice. However, as the former CEO of large companies, and someone who has led from the top, I am aware that leaders often find out later about a disastrous weakness in our flank that only those at the bottom could anticipate.

I flatly refuse to languish at the proverbial bottom silently, rather to shout a warning: This is a time for bold action in reforming our system and our dialysis patients need it more than anyone. Our leaders must listen attentively to the story on the ground before that story is told through its tragic, broad-reaching outcomes.

We are on the precipice of a dreadful network effect between nursing homes and dialysis centers, which can cause a mass infection of our elderly, eventually affecting the broader population as well.

But there is a safer way to administer this lifesaving care, and we must urgently make plans to deliver dialysis within nursing home and long-term care facilities, and further to accelerate the provision of dialysis for those able to do it in their home. We must save our elderly and our broader population from this deadly blind spot.

Levin is a former CEO of Time Warner.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.