In the ashes of post-war Japan, a young Prince Akihito broke with tradition for an interview with an American

Long before he became the Japanese figurehead, before he shattered centuries of tradition by marrying a commoner and certainly long before he ever dreamed of abdicating his throne, the man who would become Emperor Akihito did something else unusual.

As a young crown prince in the ruins of postwar Japan, he agreed to an interview with an American journalist — something that would have been unthinkable just months before. Attended by his royal handlers in Akasaka Palace, he professed his love of Mickey Mouse and Peter Pan, and offered greetings to American children: “Let’s be good friends.”

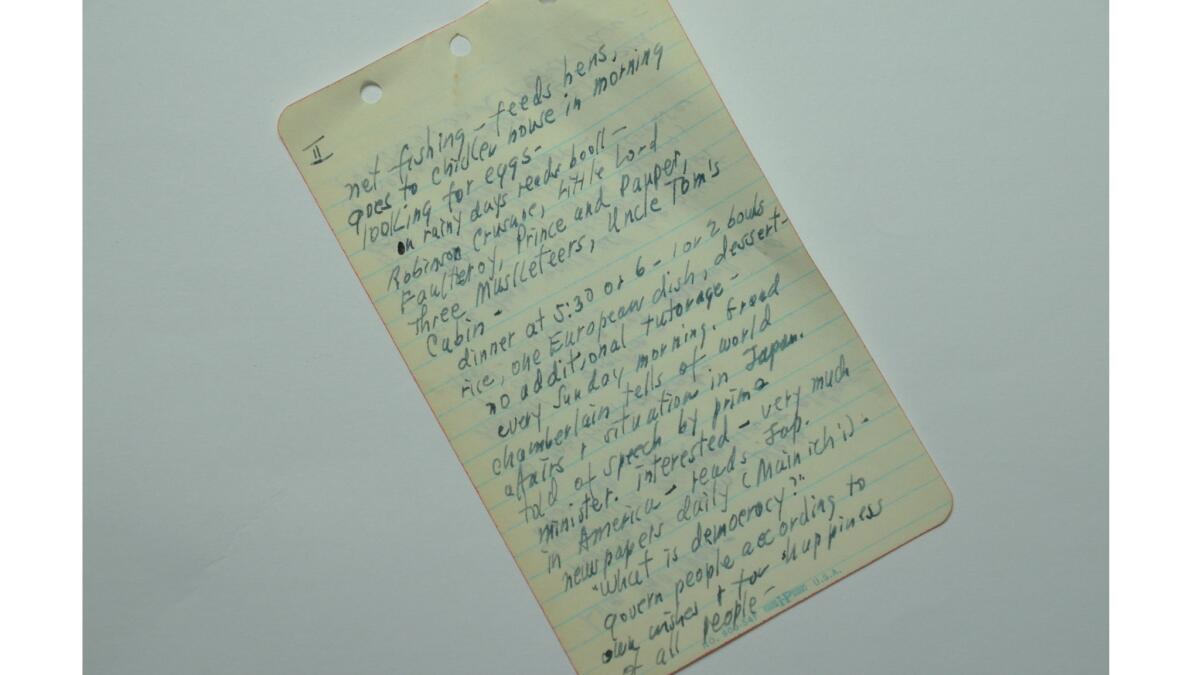

I know this because the American who interviewed him was my father. The news that Akihito was considering abdication sent me rummaging through an old cigar box of my dad’s wartime journals, where I found the notes — the fountain-pen ink barely faded after more than 70 years — that chronicled their meeting on Dec. 19, 1945, less than four months after World War II ended with the Japanese surrender.

My dad, Morrie Landsberg, who died in 1993, had been an Associated Press war correspondent in the Pacific. He covered some of the decisive battles of the war — Saipan, Guam, the Philippine Sea, Iwo Jima. He was on a Navy flagship off Iwo when his AP colleague, photographer Joe Rosenthal, captured the famous photo of the flag-raising.

“American flag flies from top Mt. Suribachi,” my dad wired. He was on Guam when Pacific Fleet headquarters there made the announcement that an atomic bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. And he was on the deck of the battleship Missouri when Japan formally surrendered.

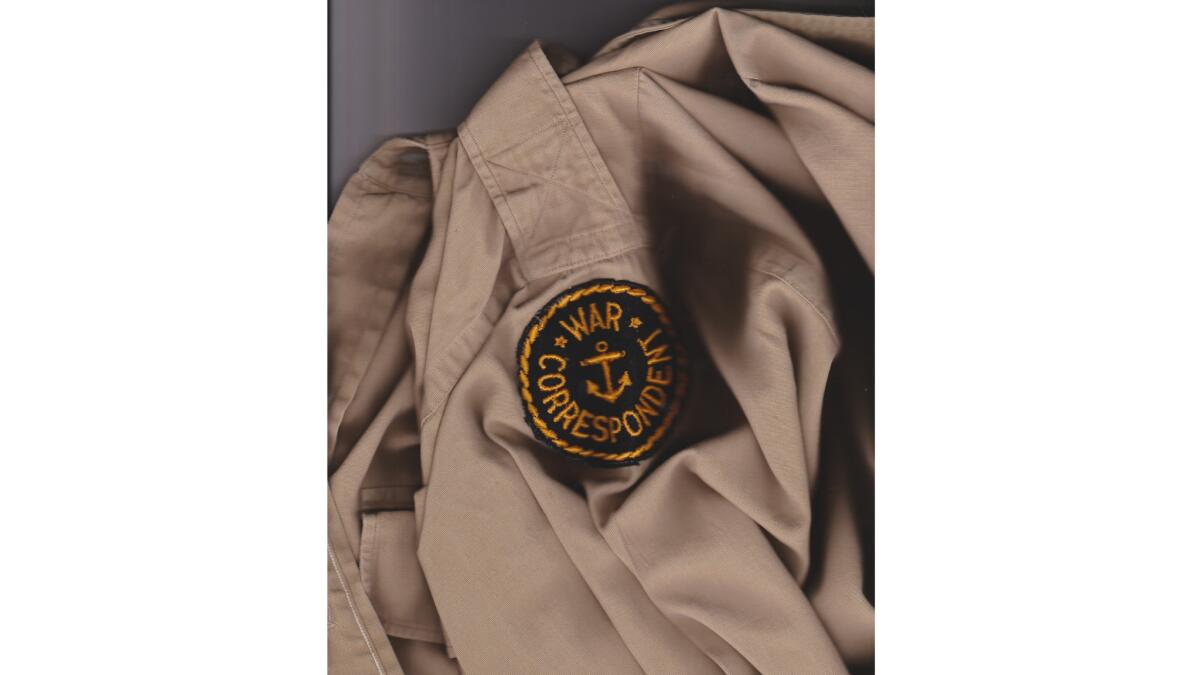

The khaki shirt of his war correspondent’s uniform still hangs in my closet, a reminder of a time when the separation between journalists and the U.S. military was less robust than it is today. He was probably wearing it when he interviewed Akihito.

There wasn’t much remarkable in what the 11-year-old prince had to say that December day. He was both young and sheltered, having been whisked out of harm’s way during the war and treated since birth as someone elevated from the scrum of humanity.

Still, the royal family’s decision to have him submit to an interview at all was a hopeful sign that Japan was willing to accept its defeat and move forward, if necessary abandoning some of the traditions that had made soldiers willing to die for Emperor Hirohito, Akihito’s father and the divine head of Japan under the ancient Shinto faith.

This was not a coincidence.

Four days before the interview, Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the supreme Allied commander in Japan, had issued a confidential directive — a yellowed copy is in my father’s papers — ordering “the separation of Shinto from the state; the removal of militaristic and ultra-nationalist ideology from Shinto doctrine; and the elimination of Shinto from the schools.”

MacArthur had, of course, agreed to allow Hirohito to remain the emperor, at least in title, thereby ensuring some continuity of Japanese culture. But his powers were stripped; Japan was to be a democracy, remade in the U.S. image, and no longer ruled by a monarch.

“What is democracy?”

Those words are also in my father’s notes.

Akihito had asked that question a few weeks before, according to Baron Hozumi, the grand chamberlain to the prince. Hozumi said he told the prince that it meant “governing people according to their own wishes and for the happiness of all the people.”

There was nothing there about self-governance. Still, it suggested that the baron was either unusually progressive for a man in his position, or he recognized that there was a new sheriff in town. In any event, he said, the prince had liked the idea.

Akihito has seemed, in some ways, to be a man not fully comfortable with the hand he was dealt. His decision to marry a commoner — shocking at the time — certainly suggested that he was chafing at the strictures of his position. And he has gained a reputation over the years as a reformer in other ways.

He is also said to be a bit shy — no surprise, considering his childhood.

The prince, the baron said in that 1945 interview, went to the School of Peers, where he played with other children — the children of royalty, to be sure. “No distinction from others,” my father had jotted down, although I doubt that he fully believed that. At night, the prince spent time alone with his toys or played cards with the grand chamberlain, a man who was then in his early 60s. Hozumi has been described elsewhere as a genial aristocrat, but nowhere as an 11-year-old’s ideal playmate.

The prince liked to build models — especially American ones (where he got them was not explained). And, in a sign of the interest in the natural world that would later lead him to become a marine biologist, he spoke of his private chicken coop and the swans that he regarded as his pets.

He seemed less comfortable with people. He would answer only written questions, Hozumi said, explaining: “He might get flustered talking to a stranger.”

It would be more than 40 years before Akihito succeeded his father as emperor. Now 82, he is reaching the final days of his reign. Somewhere in the recesses of his memory must be images of a lost world, of the boy who loved swans and of the American who came on a wintry day to meet him.

mitchell.landsberg@latimes.com

ALSO

Japan’s emperor addresses nation, indicates he wants to abdicate

Japan’s emperor will give a video speech. What’s the big deal?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.