The Bible described it as the perfect, pure blue. And then for nearly 2,000 years, everyone forgot what it looked like

Forty-nine times the Bible mentions a perfect, pure blue, a color so magnificent and transcendent that it was all but impossible to describe.

Yet, for most of the last 2,000 years, nobody has known exactly what “biblical blue” — called tekhelet in Hebrew — actually looked like or how it could be re-created.

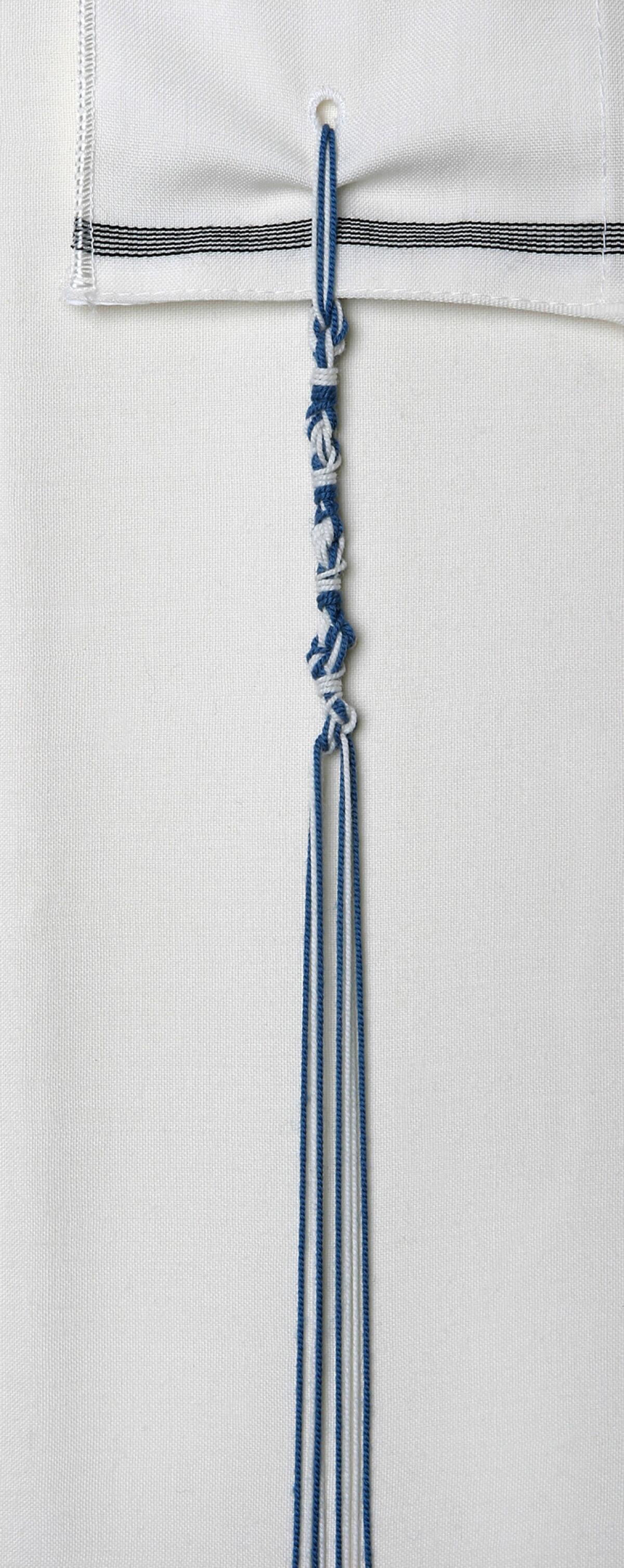

At the time of the Second Temple, which towered above Jerusalem until it was destroyed by the Romans, a blue dye of the same name was used to color the fabric used in the clothing of the high priests. Jewish men are still commanded to use a tekhelet-tinted thread in the knotted fringes of their prayer shawls, though what that might look like remained unclear for years.

Maimonides, the medieval Sephardic philosopher, described tekhelet as being the color of “the clear noonday sky.”

Rashi, the 11th century French rabbi and scholar, said it was “the color of the evening sky.”

Tekhelet was “the most prized color you could attain,” says Amanda Weiss, director of Jerusalem’s Bible Lands Museum.

A possible clue to the ingredients that combined to make tekhelet came from the Talmud, the canonical body of rabbinic texts, in which a man named Abaye asked an elder “this thread of tekhelet, how do you dye it?” He was told that “the blood of the snail and chemicals” (apparently caustic soda or sodium carbonate) had to be boiled together to create the dye.

It was not much to go on.

Yet the drive to find a color so perfectly blue could not so easily be turned off.

The modern-day quest to untangle the riddle of tekhelet was launched by a rabbi, an occupational therapist, two chemists and a pair of scuba divers — one of them with a doctorate in physics. Together they hoped to rediscover the secrets of the lost pigment.

Knowing that the dunes of Dor Beach, a popular spot on Israel’s northern Mediterranean shore, hid ruins of ancient dyeing vats and unexplained mounds of discarded snail shells, the explorers set off in the mid-1980s to identify the species of sea snail they believed might hold the key to finally revealing what tekhelet looked like.

Dor Beach’s Murex trunculus snails seemed promising, but the purplish ink produced by secretions of their glands ended up dyeing cloth yellow.

It fell to Otto Elsner, a chemist at the Shenkar College of Engineering and Design near Tel Aviv, to discover that when the ink extracted from the snails was exposed to the sun, it transformed into “deep sky blue.”

Was it, finally, tekhelet?

With a blue similar to that of a flawless sapphire, tekhelet was an arresting hue, and everyone seemed satisfied that the mythic color had finally reappeared.

The explorers eventually established Ptil Tekhelet, an organization that produces and promotes tekhelet and, in 2012, published a book by Baruch Sterman, the scuba-diving physicist, on the rediscovery of “biblical blue” — “The Rarest Blue: The Remarkable Story of an Ancient Color Lost to History and Rediscovered.”

The account, and their pursuit of the vanished cerulean, kindled in Weiss’ mind the idea for an exhibit spanning the history of blue.

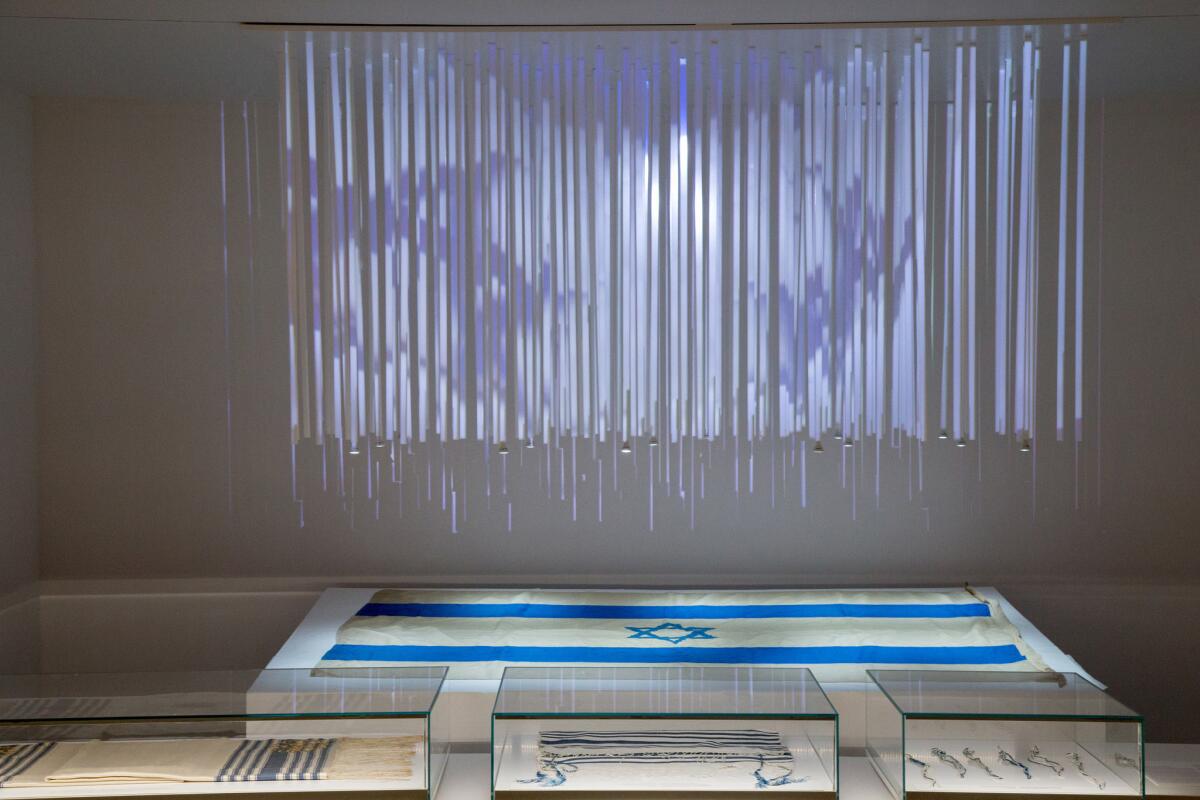

Now an exhibit at the Bible Lands Museum, “Out of the Blue” explores the mystery of how the alluring color became associated with nobility and divinity alike, how it was lost and then found, and even offers visitors take-home kits to create blue cotton thread the way Jesus and his followers did long ago.

The show includes fragments of cloth found in Masada, the Roman-era fortress, alongside jewelry made with Afghan lapis lazuli, the azure stone prized for its intense deep blue threaded with gold.

The Masada textiles are dyed with M. trunculus secretions that were obtained at a rate of a few drops a day, according to exhibit curator Yehuda Kaplan, requiring thousands of snails to dye a single garment.

The exhibition’s logo, which looks like a wreath of shining sapphires, was inspired by the remnants of the beach-side pools used to harvest and raise the snails in what may be the earliest known example of aquaculture. The museum is organizing expeditions to the site.

Yet the exhibition is not just about tekhelet and its ties to Judaism, but “the significance of blue in all the ancient Near East.”

From earliest human history, from the Levant to North Africa, blue has been considered a lucky color. It is still common to see shutters or rooftops painted bright blue as a protective amulet. One legend has it that as the evil eye descends toward Earth, a flash of sky-blue disorients it, sending it away.

The superstition reached Europe, and from there the New World. An 1898 compilation of British customs published in the quarterly journal Folk-Lore explains that the “something old” and “something blue” a bride wears “are devices to baffle the Evil Eye,” without which the malevolent forces would “render her barren.”

The Jerusalem exhibit includes artifacts decorated with Egyptian blue, considered the world’s oldest artificial pigment, and lapis lazuli, when not used to adorn jewelry, was ground up to make ultramarine, the most desirable and costliest Renaissance-era pigment.

Such was its luxury that European royal courts adopted the color as a representative banner.

King Louis IX of France, the 13th century saint, regularly wore a deeper, possibly more violet version of today’s royal blue.

The Jewish prayer shawl, called a tallit, inspired the blue stripes of Israel’s national flag. The standard that flew outside the United Nations in May 1949, when Israel was admitted as a member state, closes the exhibit — and demonstrates the universal draw of blue, as seen in the pale yet vibrant blues chosen for the flags of the United Nations and the European Union.

The fashion historian and curator Yaara Keydar says that textile dyeing was historically a Jewish occupation, and in the desolate centuries in which the art of tekhelet was lost, the dyers and brokers traded in indigo, a plant-based purplish-blue colorant.

Like tekhelet, indigo was a rare commodity and hard to obtain, “and therefore became a sought-after luxury item,” she says.

Both pigments, she says, form “a cult of blue” that lives on, including in vintage Karl Lagerfeld and Levi’s.

Tarnopolsky is a special correspondent.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.