Editorial: The largest methane leak in U.S. history began one year ago at Aliso Canyon. What have we learned since then?

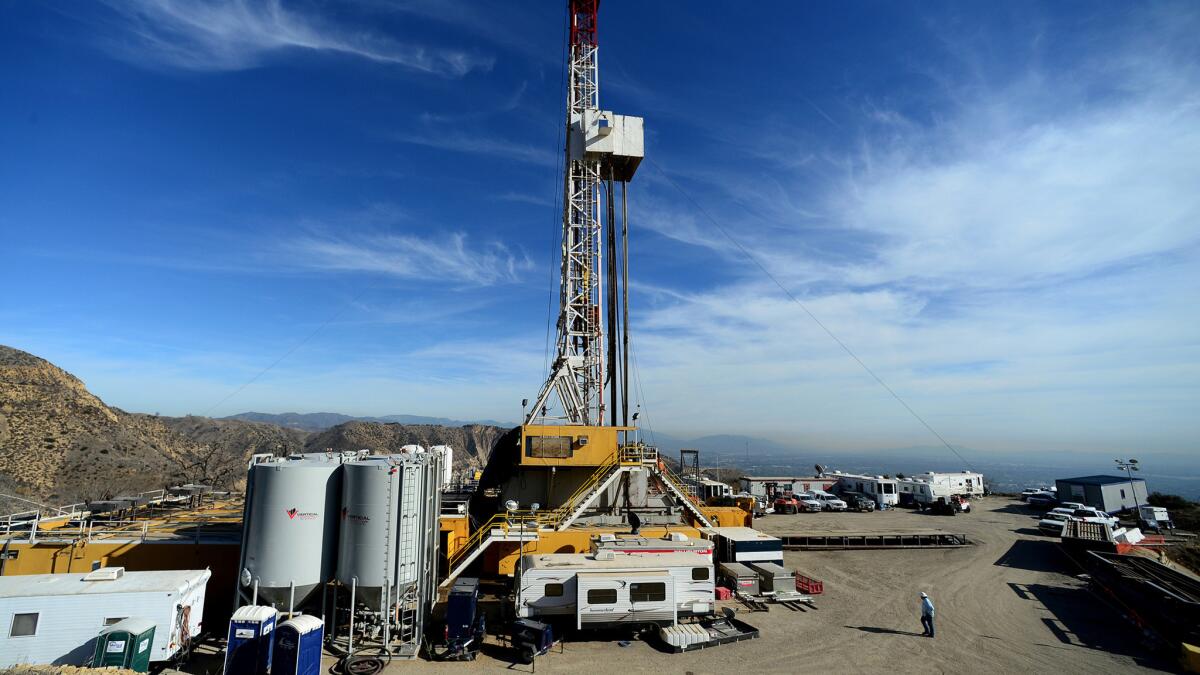

One year ago, state oil and gas officials received a report of a small, routine methane leak at the Aliso Canyon underground natural gas storage field in the hills north of Porter Ranch. But as it turned out, the leak was neither small nor routine.

Over the next four months, the busted storage well caused the largest leak of methane — a potent greenhouse gas — in U.S. history. It released about 90,000 metric tons, equivalent to more than a million cars driven for a year. Gov. Jerry Brown declared a state of emergency, while the Southern California Gas Co. scrambled to stop the flow. More than 8,000 families temporarily relocated because of the sickening smell of the gas. Even today — months after the leak was plugged on Feb. 17 — some Porter Ranch residents say they still suffer from nausea, nosebleeds and rashes.

The leak was a wake-up call. Too few people had recognized the tremendous risks of Aliso Canyon — that an aging facility operating under grossly outdated and inadequate standards could wreak havoc on public health and the environment. About 80% of the facility’s wells were built before the 1970s, and Southern California Gas knew they were corroding and failing at an increasing rate. But there were no rules mandating frequent inspections or upgrades. What’s more, government officials didn’t seem sufficiently concerned that the state’s energy supply had become so heavily dependent on Aliso Canyon.

The Aliso Canyon crisis kick-started investments and planning that should make Southern California less dependent on natural gas in the years ahead.

In response to the leak, the facility was temporarily closed and the Legislature passed a law requiring new safety procedures for the state’s 14 underground gas storage facilities that may be the strictest in the nation. The Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources is expected to adopt the regulations next year.

The closure of the San Onofre nuclear power plant, the decline in coal and other factors have resulted in a significant increase in electricity generated from natural gas — and greater reliance on Aliso Canyon, the largest storage facility in the state. State officials warned in April that the temporary closure of Aliso Canyon could cause up to 14 days of rolling blackouts during the summer because the power plants that fire up to meet high electricity demand wouldn’t be able to get the gas they needed.

That didn’t happen. Utility officials say the region got lucky with a mild summer and lower-than-normal electricity demand, but they warn that the risk remains as long as Aliso Canyon is closed.

The good news is that the Aliso Canyon crisis kick-started investments and planning that should make Southern California less dependent on natural gas in the years ahead. Local utilities have spent tens of millions of dollars in recent months on energy-efficiency programs to help cut demand for electricity and gas. Pushed by the California Public Utilities Commission, both Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric signed contracts for energy storage projects that could be ready for the winter. The challenge of solar, wind and other renewable energy sources is they can only supply electricity when the sun is shining or the wind is blowing. But the development of large-scale batteries that could hold that green power would reduce the need for some natural gas power plants.

Aliso Canyon also helped push the Los Angeles City Council and Mayor Eric Garcetti to direct the Department of Water and Power to study what it would take to end the utility’s reliance on fossil fuels and to get 100% of L.A.’s electricity from clean energy. That’s significantly more ambitious than California’s already aggressive mandate of 50% renewable energy by 2030. DWP officials say it could take 25 years to rebuild the region’s electricity system. It’s absolutely essential to begin this difficult work.

Southern California Gas says it has completed safety reviews at most of its wells, and the company is expected soon to seek permission to reopen the storage facility. There will surely be an important debate over whether Aliso Canyon is safe enough or truly vital to the region’s immediate electricity needs. But in the long term, it’s clear that the costs of fossil fuels — on public health, the environment, the climate — are too great and that we should end our reliance on them as soon as possible.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.