Commentary: The newest ‘Cinderellas:’ -- finding an unexpected virtue

I thought I was over “Cinderella.” I assumed the whole world was over “Cinderella” right along with me.

Not all of it, of course. We’ll likely never outgrow the thrill of the radical makeover and the big reveal. We’ll always line up for a fairy godmother, whatever her (or his) brand of magic: Oprah, Supernanny, Jillian Michaels, Gordon Ramsay.

But all the cultural assumptions and gender politics embedded in “Cinderella “ -- especially the ascendant version, the 1950 animated Disney feature--we’ve rooted all of those out, deconstructed and subverted and revised them. Right?

There was the “Shrek” franchise, which frantically mashed up and sent up fairy tales for children too young to have encountered, much less questioned the sociopolitical framework of, the originals.

And then the Disney updates themselves: “Enchanted,” “Tangled,” “Brave” and “Frozen,” with their clamorous insistence that girls can do anything, anything at all, and that cleverness, pluck and athleticism are just as important as beauty. (So do your homework and sign up for those archery lessons, girls!) We women have to rescue ourselves, these films attest, because marriage is not salvation but an equal partnership between two flawed if well-meaning individuals.

And after this winter’s film version of the cynical musical “Into the Woods,” in which Cinderella just isn’t that into the prince, I was fairly satisfied with where we as a society had landed on this fairy tale.

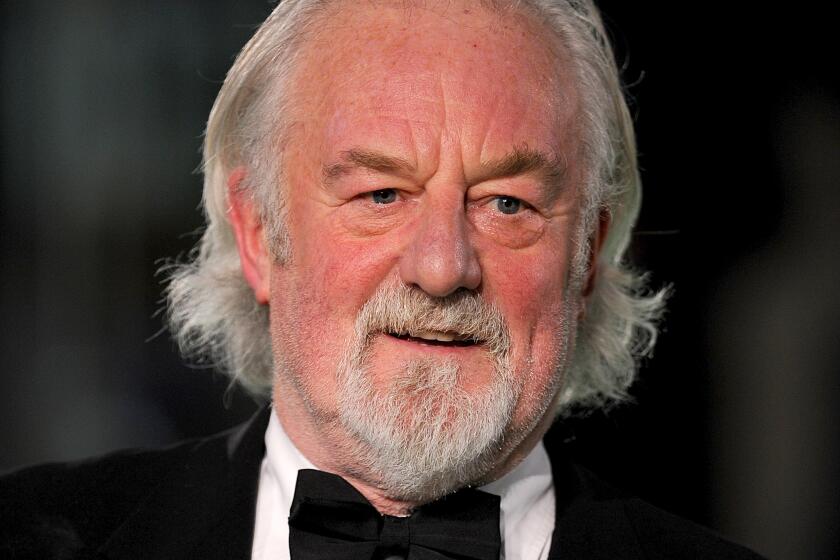

I doubted that two newcomers to the canon--the updated Broadway version of “Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella,” now at the Ahmanson Theatre, and Disney’s new live-action film, directed by Kenneth Branagh--could have anything further to say on the matter.

Then I saw both, over the course of two tulle-filled days. They weren’t what I was expecting.

Although they’re very different from one another, both straightforwardly and unapologetically endorse the value of kindness.

Yes, kindness -- that dull old forgotten arrow in the human quiver. You know, the quality everybody routinely preaches to children, the one that, children can’t help noticing, is not always effective in getting them their way.

Kids are expected to be themselves, look out for No. 1, never give up on their dreams and be the best at everything they try. And, they quickly figure out, people who succeed in these goals just can’t waste time being kind. They have to be ruthless, manipulative, cunning, quick-witted, persistent and not hung up on hurt feelings, their own or others’.

Let’s face it, in our culture, meanness is often seen as sexy, hilarious, cool and dazzling, while kindness is for saps. Our surprise and gratitude when we encounter it are sometimes tinged with derision.

More than once, in bringing up my children, I’ve wondered if encouraging them to be considerate, to share and to wait their turn might actually disadvantage them in the race to the top. I’ve looked around and thought, “Am I the only sucker still selling this drivel? Is anybody buying it?”

Spoiler alerts: In “Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella” (the original book and score were written for television in 1957; this latest update is by Douglas Carter Beane), the guests at the ball are invited to play a game called “Ridicule,” in which women trade Joan Rivers-style barbs. Inevitably, Cinderella (Paige Faure) has to face her wicked stepmother, Madame (Fran Drescher).

But Cinderella plays the game badly: She sincerely praises Madame’s outfit. Madame is bewildered, stumped and silenced. The other guests, freed from the merciless trap of snark, start trading compliments. “I like how you turned everything around just then,” the Prince (Andy Huntington Jones) tells Cinderella.

In the Branagh film, which has a screenplay by Chris Weitz, Cate Blanchett plays Madame as the ultimate mean girl, jealous, scheming, soigné, an artist of the backhanded compliment and the stab in the back, with eyes of green ice.

Now I’ve seen my share of movies about mean girls--”Mean Girls,” for example, along with its gory, black-hearted predecessor, “Heathers”--and in all of them, the mean girls get theirs.

So I waited for Madame’s inevitable defeat. And it came. But it came via a device I hadn’t encountered in so long that I’d almost forgotten it existed: forgiveness.

Cinderella (Lily James) forgives her stepmother. It’s such a rare snark-free moment in contemporary fairy-tale remakes that I felt faintly embarrassed by it.

I didn’t necessarily expect the stepsisters to have their eyes pecked out by birds, as in the Grimm Brothers’ “Aschenputtel” (1812), but I was banking on a major put-down reflecting our modern sense of female empowerment. Maybe Cinderella would dunk a basketball on her way out the door. Something seriously woo-hoo-worthy.

Instead, this preachy, unironic, even biblical moment.

Beane’s rethinking of Rodgers + Hammerstein’s musical is populated by progressive and well-meaning people. One of the stepsisters is a blossoming liberal, and the prince is so forward-thinking that Cinderella’s efforts to conceal her lowly status by running away at midnight start to seem weird. He’d obviously be fine with it.

Yet somehow Cinderella’s kindness doesn’t feel phony or simpering.

In an interview in the program, Beane says he found inspiration in Charles Perrault’s original French story, “Cendrillon” (1967), which ends with this moral: “Beauty in a woman is a rare treasure that will always be admired. Graciousness, however, is priceless and of even greater value.”

As a child I didn’t buy that moral, and I didn’t like the forgiveness. One reason I took so enthusiastically to the revisionist retellings of “Cinderella” is that I felt left out and disheartened by the lessons of the 1950 Disney movie:

1) Be the most beautiful girl in the kingdom.

2) Have preternaturally small feet. (As the psychoanalytic theorist Bruno Bettelheim pointed out, the earliest written variant of “Cinderella” comes from China in the 9th century A.D.: “The modern hearer does not connect sexual attractiveness and beauty in general with extreme smallness of the foot, as the ancient Chinese did, in accordance with their practice of binding women’s feet.”)

3) Do all the dirty work without complaining--in fact, while singing.

4) Don’t stick up for yourself when your family gangs up to mock you, call you names and rip up the dress you stayed up all night to sew.

5) Talk to mice.

6) When you can’t take it anymore, collapse weeping in the garden, and a fairy godmother will arrive.

But now I think I got “Cinderella” all wrong.

In Branagh’s film, so earnest and sentimental that it first provoked, then stunned into silence my own stepmother-like snark, Cinderella’s reticence and acquiescence in her own mistreatment are presented not as weakness but as the results of her commitment to kindness. After she promises her dying mother that she will be courageous and kind, she follows this code no matter what it costs her.

It costs her, as courage and kindness tend to do. That she is ultimately rewarded is what marks her story as a fairy tale.

In a society where it has become common for teenagers to goad one another to suicide, kindness doesn’t always pay off so well. It’s not cool to be the goody-two-shoes whining, “Be nice!” We’d rather take down the mean girls by giving them a taste of their own medicine, sending birds to peck out their eyes.

So it’s unrealistic to expect that these dueling “Cinderellas,” neither perfect but each winsome in its own way, will turn everything around. They probably won’t usher in a new era of kindness or presage exclusively warm and complimentary online comment threads.

Still it’s surprisingly heartening to be reminded that kindness is an admirable goal.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.