Getting fast-food employees worked up over the minimum wage

Naquasia LeGrand was an apolitical fast-food worker before meeting a union organizer. Now she’s one of the most vocal backers of a movement to double the $7.50-an-hour minimum.

The union organizer found Naquasia LeGrand on her lunch break, sipping coffee and wearing a hat emblazoned with the logo of her employer, KFC.

She was about to return to boxing coleslaw and chicken tenders when he introduced himself and asked how she was doing, how she was surviving on $7.25 an hour, the minimum wage. The organizer, Ben Zucker, wanted to know whether she might want to join a group of workers trying to get higher pay.

It wasn't something she'd thought much about. The job was a detour between high school and that computer degree she was hoping to get someday. A way to help support her aunt, grandmother and cousin, who lived with her in a cramped apartment in one of the most expensive cities in the country.

She didn't think of herself as someone who needed to join a union or someone who would be a fast-food worker for long.

Still, the two exchanged numbers in front of the restaurant, across the street from tire shops, a bodega and a Latino church. Without knowing it, LeGrand had begun a process that would change her from an apolitical fast-food worker to one of the most vocal members of a growing labor movement.

LeGrand, 22, is the kind of convert unions desperately need as they try to reverse a decades-long decline in membership. The new front in that effort is fast-food restaurants, and union leaders, although they are optimistic, know that unionizing these workers won't happen overnight.

It took years for a janitors' campaign that began in Los Angeles in the 1980s to achieve results, for instance, and that effort occurred when unions were stronger.

The fast-food workers movement, however, has been successful in rallying disconnected workers around the minimum wage.

"Nothing is going to happen instantly," said Ruth Milkman, a labor scholar at City University of New York. "But … it has done a lot already to make people think unions can make positive change."

The movement started out small, in New York City, with the Service Employees International Union providing money and support to pull off a one-day strike in November.

Fast-food workers in Detroit, Chicago and St. Louis had followed by May. On Aug. 29, workers in 50 cities across the country, including Los Angeles, demonstrated outside restaurants, demanding union representation and $15 an hour in pay.

The protests have gained some traction in part because the profile of fast-food workers has changed. They are no longer just teenagers trying to earn extra cash. After the recession, an increasing number of older workers came to depend on these jobs to support families. Now that the economy is improving, the question is whether they will stick around; the industry still has notoriously high turnover.

The initial approach

LeGrand's grandmother, a postal worker, disliked unions.

She thought they didn't do much for their workers, despite collecting millions in dues. When LeGrand first received a text message from Zucker encouraging her to attend a unionizing meeting, her grandmother spoke up. No way should LeGrand go. She could lose her job, and then where would they be?

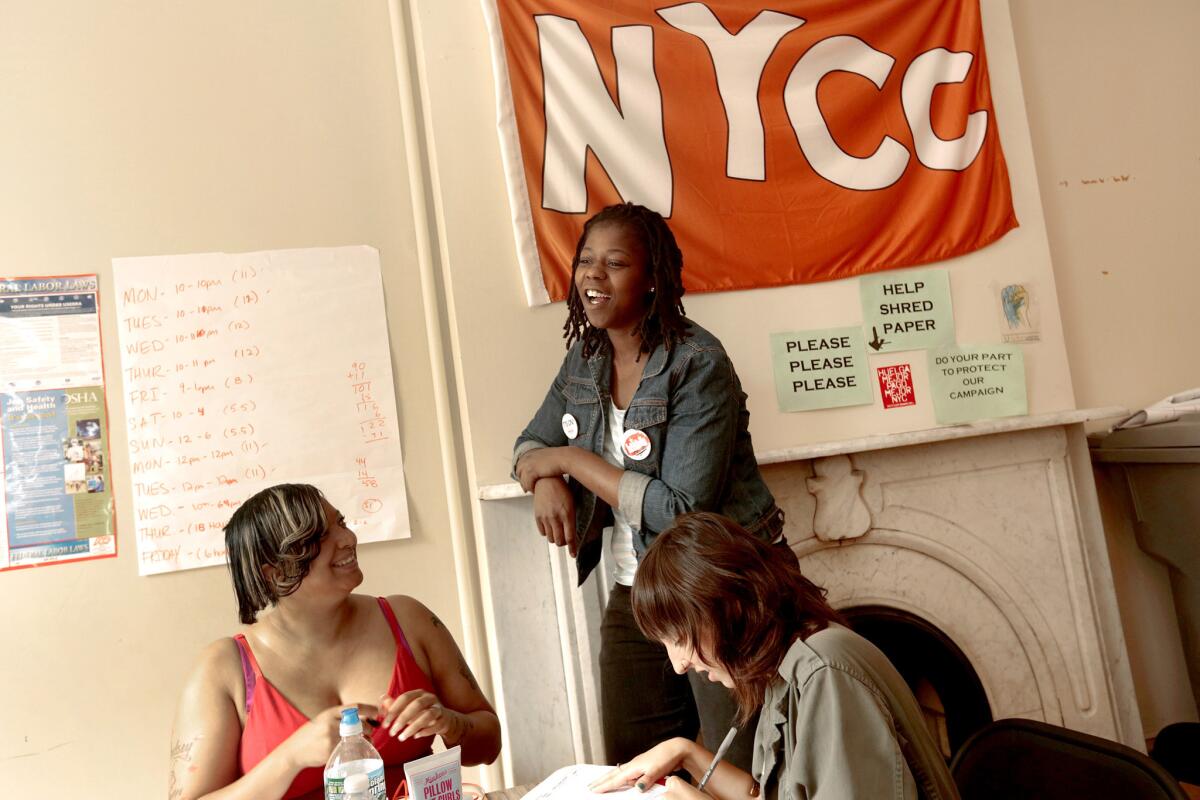

Working from the New York Communities for Change office in Brooklyn on Aug. 27, LeGrand calls fast-food restaurant workers to encourage them to take part in a protest two days later. More photos

Grandmother and granddaughter argued in their two-bedroom apartment in an aging brick housing project in south Brooklyn. LeGrand knew the family needed her salary to help pay the $1,300-a-month rent, so she ignored Zucker's calls and tried to forget the talk about raising the minimum wage.

She had a lot to lose by attending a union-organizing meeting. In fast-food work, shifts are determined by managers. If she got involved, she could be labeled a troublemaker and given fewer shifts. Besides, who had time to go to weekly meetings to talk about doubling salaries — something that seemed highly unlikely?

But Zucker was persistent.

He got on speaker phone with LeGrand and her grandmother, a stern woman with long dreadlocks who has spent decades caring for children and grandchildren. They talked for an hour about what Zucker was trying to accomplish. He assured LeGrand that the union wasn't some scam, and as she thought about it on the buses and trains she rode to work, she found herself trusting him more.

When you make $300 a week, how can you ignore someone saying you can earn more money to better support your four-person household, maybe even get a bedroom of your own someday, and not have to share a room with your grandmother?

A few weeks later, LeGrand attended a union meeting in Brooklyn and brought along seven workers from her store.

The growing campaign

She didn't know it at the time, but Zucker was one of 40 paid organizers fanning out across New York to persuade fast-food workers to protest.

The movement began when a community group, New York Communities for Change, surveyed residents about school closings and noticed that many said they didn't have the time or money to do anything but work. Many of them juggled two or three jobs. Most of them were fast-food workers making minimum wage.

Communities for Change contacted the SEIU, which had organized some custodial and food-service unions. Recognizing an opportunity to increase its membership and political clout, the SEIU agreed to provide financial support and brought in other community groups. Any efforts to raise the minimum wage would help all workers, union leaders figured.

At LeGrand's first meeting, organizers showed her KFC's annual profits. She felt disbelief, then anger, then hope. Surely she deserved more pay if David Novak, the chief executive of Yum Brands Inc. — which owns KFC, Taco Bell and Pizza Hut — took home a compensation package of about $11 million last year.

There's no central place where fast-food workers congregate, making them particularly difficult to organize. So the activists needed help to reach more people.

When Zucker asked LeGrand to recruit other workers, she hesitated. Many of her colleagues didn't want to get involved. One of her close friends at KFC stopped talking to her, tired of hearing about unions.

But at the weekly meetings with other workers, she saw more people getting involved in the movement and felt compelled to do something. LeGrand kept hearing co-workers talk about how hard it was to pay the bills, so she started turning those complaints into an argument for organizing. Can't afford the rent this month? Then why not attend a meeting that could help change that? When your pay is so low, what do you have to lose?

Have you ever thought of joining together with some people trying to get a higher wage?"— Naquasia LeGrand

It became a way for her to talk to people about the movement, even those she didn't know. That's how she recruited the man in the Domino's Pizza uniform she kept seeing on the train. She approached him one day as he carried a bike down the stairs at her subway stop.

"Hey, you guys hiring?" she asked, ignoring the butterflies in her belly.

He wasn't sure, he said.

"How much do you make, anyway?" she asked.

Minimum wage, he replied — $7.25.

"Must be hard to live on that," she said.

Yes, he said.

"Have you ever thought of joining together with some people trying to get a higher wage for fast-food workers?" she asked.

After talking a few more minutes, they exchanged numbers. She texted and called until he agreed to come to a meeting. Then she asked him to bring a friend.

The biggest strike

The eve of the latest strike was the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s "I Have a Dream" speech. LeGrand began that day working a morning shift at one KFC and ended it on the night shift at another.

LeGrand, center, talks with fellow organizers Lyndsey Sutton, left, and Jessica Wolff at the New York Communities for Change office in Brooklyn on Aug. 27. "This is what I do, it's part of me now, it's like there's no stopping it," she told protesters two days later. More photos

At 2 a.m. she went straight to a room above a tattoo parlor in a grimy Brooklyn building where the labor campaign is headquartered. She climbed the worn carpeted stairs to the fourth floor, where handwritten charts were taped to the walls, and began to sort through sheaves of paper, figuring out who needed to be picked up in a van, who needed to be called and reminded to strike, who needed to give their employers signed notice about the strike.

Later that afternoon, after attending demonstrations around the city in a day that wavered between overcast and scorching hot, LeGrand climbed onto a stage in front of hundreds of protesters to kick off a rally in Union Square. She was wearing a red, white and blue shirt with the slogan "Fast Food Forward." She was surrounded by TV cameras, politicians, reporters.

"This is my fourth strike," she yelled, her voice raspy from a day of shouting. "This is what I do, it's part of me now, it's like there's no stopping it."

The crowd cheered. One man banged on a bongo.

"What do we want?" she called out.

"Fifteen dollars and a union," the crowd called back.

The chanting was a little disorganized. But that didn't bother LeGrand. She reveled in the show of support for a movement that barely existed a year ago.

"It's good seeing all you beautiful people coming together to support this movement that's taken national," she said, to a sea of supporters wearing shirts like hers. "It's not just New York no more."

Follow Alana Semuels (@AlanaSemuels) on Twitter