Americans Still See Big Opportunities in Russia

Is the jailing of one of Russia’s richest men curbing enthusiasm among U.S. businesses for investment in that country?

The short answer is: nyet. Big oil and industrial projects are going forward. Meanwhile, the outlook remains bright for ventures in Russia -- both for Russian entrepreneurs financed by U.S. funds and intrepid Americans who see opportunity in a changing society.

Despite the recent turmoil, “we put on a Julio Iglesias concert and it sold out,” notes Larry Namer, a Los Angeles TV executive who with his wife, Nataly Sherbakova, runs Comspan Communications Inc., an event promotion business in St. Petersburg. The couple -- she is the niece of the late Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev -- have been putting on concerts and sporting events in Russia for more than a decade.

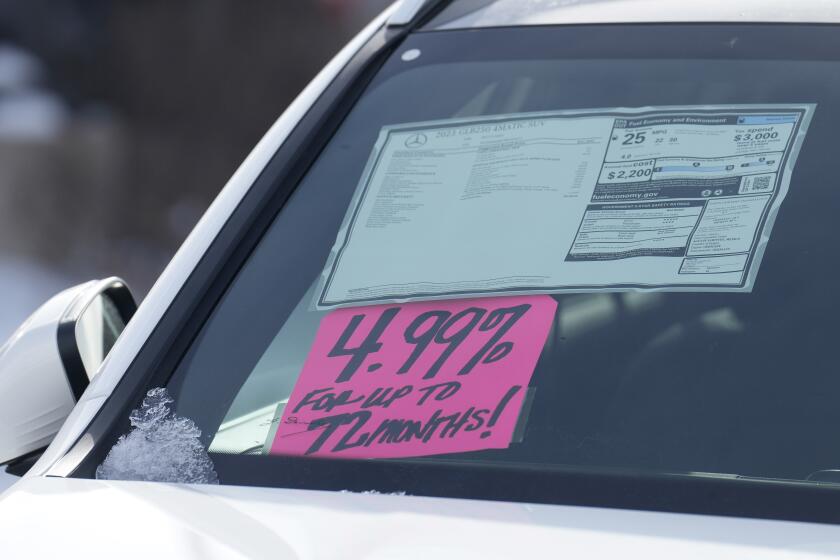

They have seen Russian business grow up. “It used to be that you could only go to the banks for sponsorship,” says Namer. “But now it’s like anywhere; car dealers, oil companies and many local businesses sponsor our shows.”

Russia may still be poor, with per-capita annual economic output only one-sixteenth that of the United States. But the vast nation of 144 million people has an abundance of scientific and technical talent.

And that is drawing attention from U.S. businesspeople such as Philip Myers, head of Typhoon Software Inc. The Santa Barbara company employs 20 programmers in Russia, and it’s poised to expand.

In partnership with two other Santa Barbara firms, Anacapa Ventures and Interface Sciences, Typhoon is launching a $2-million Russian Nanotechnology Fund. Its aim is to commercialize Russian academic research into the new technology of molecular machines.

What’s more, Typhoon’s Myers is trying to bring to the U.S. market a Russian bomb-detection device that can scan small packages and hand baggage at airports.

Yet it’s not only small companies that are swelling cumulative U.S. investment in Russia to $5 billion this year -- about one-fourth of the $19.6-billion total of foreign business investment in the country.

Ford Motor Co, for one, is making cars in St. Petersburg. Parsons Corp., the giant Pasadena-based contractor, is demilitarizing Russian SS-20 missiles and also undertaking engineering and construction work at Exxon Mobil Corp.’s $15-billion oil exploration project on Sakhalin Island.

For their part, ChevronTexaco Corp. and BP already are heavily invested in several oil development projects in Russia. And ConocoPhillips is negotiating a joint venture with Lukoil, the second-largest Russian energy firm, to develop prospects in the icy Northern Territories.

Oil is touchy. Russia’s current political trouble stems from charges of fraud and tax evasion brought against Mikhail Khodorkovsky, head of Russia’s biggest oil company, Yukos Corp.

The story behind his arrest dates to the dawn of the Russian Federation in the early 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union. There was a rush to privatize state companies, and the process proved chaotic. The government handed out to the masses millions of shares that plunged in value and then were sold. In turn, the shares were snapped up by shrewd businessmen like Khodorkovsky who became known as “the oligarchs” for their extraordinary wealth.

Before Khodorkovsky was taken into custody, Yukos had been in negotiations to sell an ownership stake to Exxon Mobil or ChevronTexaco -- a deal that could have provided him billions in cash to finance his political agenda.

President Vladimir Putin moved forcefully, sending notice with Khodorkovsky’s arrest that the Kremlin, and not the private sector, was in charge.

In the eyes of Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, the episode is reminiscent of “Teddy Roosevelt and the trust busters moving against Rockefeller and others of the 1890s.”

Other experts see a different dynamic playing out. Russian scholar Marshall Goldman of Harvard University says the clash boils down to those who want to open economic relations with the West “and the Slavophiles who do not want anybody to own Russian natural resources.”

But for all that, the Putin-Khodorkovsky affair is largely background noise on the ground in Russia.

Just Tuesday, the Swiss bank Credit Suisse Group announced that it would open an office in Moscow to assist international clients wishing to invest in the country.

“There is enormous opportunity at the entrepreneurial level,” says Jeffrey Hirschberg, an attorney with the Washington firm of Howrey Simon Arnold & White, who is a director of the U.S.-Russia Investment Fund, a decade-old government-backed venture that has poured $300 million into small to medium-sized companies there.

Among the fund’s accomplishments: resuscitating St. Petersburg’s Lomonosov Porcelain Plant, putting the business on a sound footing and allowing it to sell shares to the public last year in a modern Russian stock market. The fund also has revived a bottled water firm, a bank, a high-tech logistics firm and a company that has brought supermarkets to the middle Volga region.

Next up, says Hirschberg: a privately run, $300-million fund. “That,” he says, “indicates that the Russian economy is reaching a new maturity.”

James Flanigan can be reached at jim.flanigan@latimes.com.