Shunned by banks, legitimate pot shops must deal in risky cash

OAKLAND — The suppliers arrive at one of the nation’s largest marijuana dispensaries carrying hundreds of pounds of cannabis in duffel bags, knapsacks and baby diaper totes. They leave with those same carriers stuffed with wads of cash.

Harborside Health collects the money from thousands of customers, spending $40 to $60 a pop for one-eighth of an ounce of pot. No credit cards or checks are accepted.

That’s not by choice. Though Harborside’s business is legal in California and a growing number of other states, most banks still won’t touch the marijuana industry, fearing the federal prohibition that remains in place.

That’s a huge security problem for Harborside and hundreds of other dispensaries forced to deal in cash by the truckload. The fast-growing Oakland company stores its weed and money in a phalanx of high-grade safes, inside a vault with 18-inch walls of reinforced concrete. Thirty-six cameras and two security teams — one to watch the other — guard the business.

To pay local and state taxes, employees carry bags filled with bills to government offices, changing routes every time.

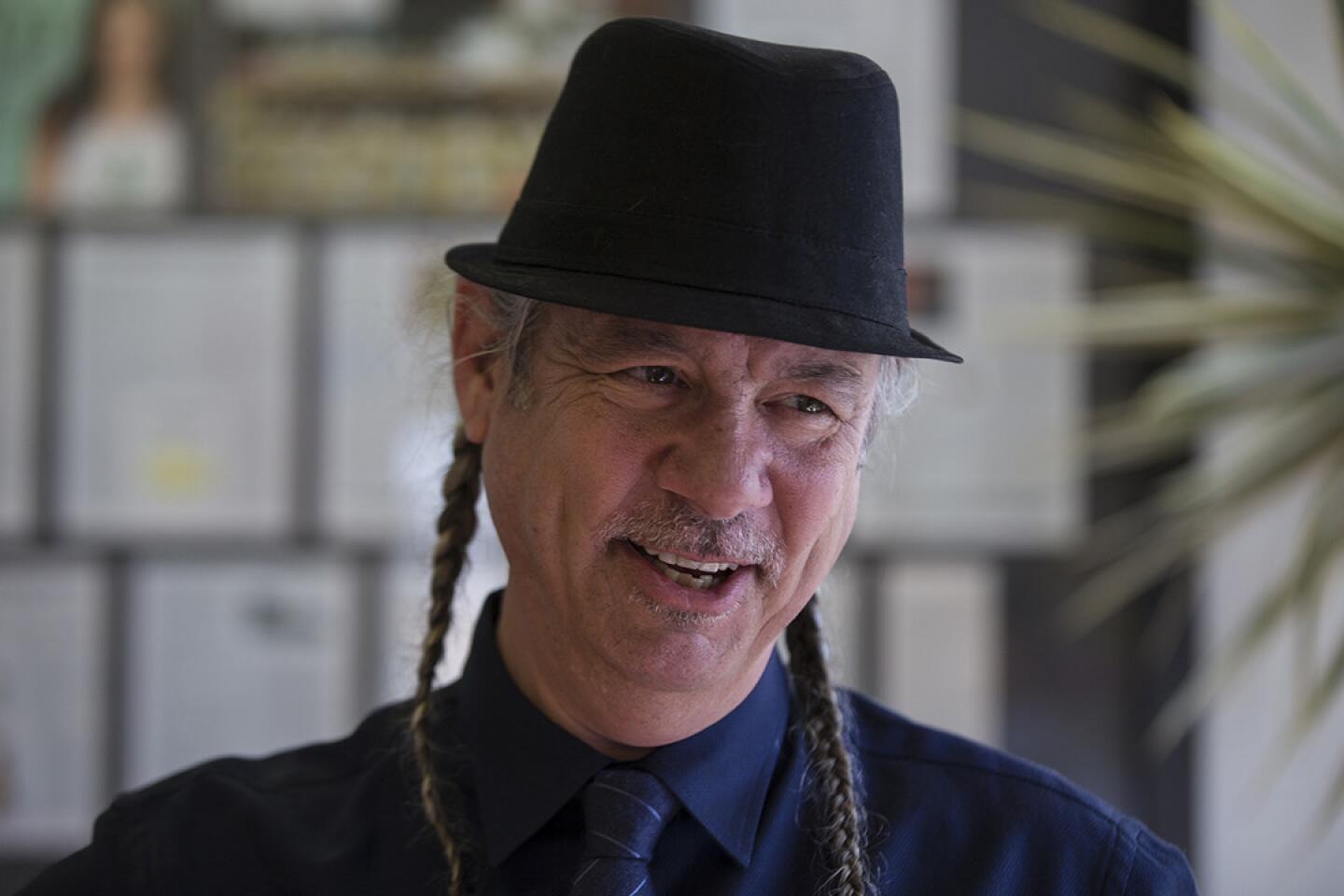

“We’ve gone through three armored car services already, and that doesn’t even include the many that refused to work with us,” said Steve DeAngelo, who co-founded Harborside in 2006. “The biggest concern to us is the threat to the well-being and safety of our staff and patients.”

As the marijuana industry expands into a multibillion-dollar business, the need for proper banking services continues to intensify. Attempts by the Obama administration earlier in the year to ease the problem have so far failed to spark widespread change.

Without banks and credit cards, financial transparency remains elusive. Taxes and basic accounting are complicated. Paying vendors and employees is both a headache and a danger.

Unless Congress takes action, the problem will grow. Twenty-three states now allow some form of legal cannabis, including Alaska and Oregon, where voters approved measures for recreational use in the recent midterm elections.

Cash is already sloshing around an estimated 2,000 medical and recreational dispensaries operating in the U.S. today, up from about 1,400 three years ago, according to the National Cannabis Industry Assn. California is home to about three-quarters of them.

The Obama administration issued guidelines in February aimed at forging a path for banks to work with marijuana businesses in states where it’s legal. It requires banks to issue reports ensuring that their cannabis-related clients are reputable, but it doesn’t absolve banks of civil charges if those reports prove untrue.

As of August, only 105 banks and credit unions were working with legal cannabis sellers, according to remarks by the director of the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. The agency did not respond to requests for an update of those numbers.

“The guidelines certainly did not throw open the doors to banking, as we had hoped,” said Taylor West, deputy director of the Denver-headquartered National Cannabis Industry Assn. “We have continued to see financial institutions feeling vulnerable.”

West has heard whispered anecdotes of measured progress.

“It happens extremely quietly,” she said. “Most institutions that are starting to work with cannabis businesses are insisting that it stay confidential.”

Lenders willing to partner with pot shops tend to be smaller community banks or credit unions.

Even with an estimated value of over $2 billion, the marijuana industry still isn’t big enough to entice major national banks to take a chance.

“There’s tremendous risk and little reward,” said Rodney K. Brown, president and chief executive of the California Bankers Assn. “The bottom line is it’s still against federal law … and you’re subject to both prosecution and loss of a bank’s charter.”

Representatives for Wells Fargo, Bank of America and JPMorgan Chase said they adhere to federal laws when choosing customers. Citi did not respond to requests for comment.

André G. Herrera, senior vice president of banking and compliance for Hypur.com, an electronic payment platform, said small banks are enticed by growing marijuana profits and willing to take the legal and reputational risk.

“Smaller banks need deposits,” he said. “Smaller banks are typically community banks, so they have a sense of purpose serving their community too.”

The bank services cost a premium, given the risk, Herrera said.

Herrera said a steady number of small lenders have also been signing up for Hypur’s compliance software, which alerts bank managers to suspicious activity, such as large transactions. It’s also able to track cash from the moment a sale is made, easing record-keeping challenges.

Not every dispensary is clamoring for a bank. Smaller operations working on the margins often view bank accounts as vulnerable to official seizure.

“They’re not motivated to open a bank account,” said Allison Margolin, a Beverly Hills criminal defense attorney with expertise in cannabis.

She cited a growing sense of fear among dispensary operators in Los Angeles, where the city attorney’s office has closed hundreds of shops to comply with Proposition D, a local measure approved in 2013.

Oakland, on the other hand, has largely embraced medical marijuana and Harborside — even fighting in court to prevent federal forfeiture action against the facility’s landlord. Harborside is one of the city’s top five contributors to sales and business taxes.

That case is ongoing, as is a legal battle with the Internal Revenue Service, which alleges the dispensary owes $2.5 million in back taxes. Harborside argues it’s being discriminated against for claiming routine business deductions.

DeAngelo opened Harborside in hopes of creating a national model for how to run a dispensary. That includes participating in charities, offering employees health insurance and ensuring the facility doesn’t invite criminal activity.

In eight years of operation, the facility has faced only two attempted burglaries. During one attempt, cameras caught two youths throwing a rock at a window. They were immediately turned away by security floodlights and a siren.

Harborside hopes to persuade other communities to welcome expansion operations — and create competitive pressure to force out less savory pot shop operators, said DeAngelo, 57, a longtime cannabis activist who was the subject of a Discovery Channel reality show called “Weed Wars.”

But coming out of the shadows requires bank accounts. Harborside has had limited success with banks, working through eight institutions over the years for brief amounts of time.

The dispensary currently holds a business account with a small state-chartered bank that allows the dispensary to handle transactions it can’t pay with cash — namely, paying federal taxes and packaging suppliers in China.

Discretion is paramount. Though DeAngelo says his bank knows the nature of his business, it helps having a generic name for the dispensary that won’t raise eyebrows.

“You have to be careful with the amount of cash and the number of transactions you use,” said DeAngelo, who declined to name the bank for fear of jeopardizing the relationship. “We try and pay as much as we can in cash and run a minimal amount through the bank.”

The heavy reliance on cash is one reason Harborside faced an especially painful IRS audit.

California medical marijuana laws require dispensaries to operate as nonprofits. DeAngelo says the money that comes into Harborside covers costs, and the rest is returned to the community in free services, charitable donations and even free weed to those who can’t afford it.

“They want detailed financial records,” he said. “But all these cash transactions make it difficult, if not impossible, to give them what they require. It puts us in a Catch-22.”

Twitter: @dhpierson

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.