Not Just Blowing Smoke

When George W. Bush became president, anti-smoking groups worried that his administration would snuff out the federal government’s massive lawsuit against the tobacco industry.

After the 2000 election, “we had a meeting in this office to talk about what could be done to prevent the case from being settled cheaply,” recalled Matthew L. Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. “We were deeply concerned.”

Meanwhile, cigarette makers had plenty of reason to hope that Myers’ fears would be realized.

The companies had long been major donors to the Republican Party. Bush’s top political advisor, Karl Rove, had served as a political consultant to Philip Morris. And Bush offered some encouragement during his presidential campaign against Al Gore. “I think we’ve had enough suits,” he told a reporter on a swing through Michigan. “The lawyers I talk to don’t feel they have a case” over at the Justice Department.

But to the surprise of people on both sides of the tobacco wars, the government’s racketeering case hasn’t gone away -- and is now about ready for trial. Opening arguments are scheduled for Sept. 21 -- five years, minus a day, from the date the case was filed by the Clinton administration. The trial in U.S. District Court in Washington is expected to last well into next year.

Justice Department lawyers are demanding stiff controls on the industry beyond the marketing curbs contained in the companies’ landmark 1998 settlement with the states. More ominous for the industry, the U.S. is seeking disgorgement of $280 billion in allegedly ill-gotten gains -- the largest amount ever sought by Justice in a civil case.

Government lawyers will portray the tobacco industry as an outlaw enterprise that launched a conspiracy of lies in the 1950s, when research linking smoking and lung cancer presented the first serious threat to the companies.

They plan to introduce a slew of internal documents in which industry figures bluntly acknowledged what they disputed in public: that smoking was dangerous and addictive, that their research programs were designed for public relations purposes and that they marketed their brands to children. Some of these documents have been previously introduced, but never in such a prominent case.

The government also will try to prove that the industry distorted the risks of secondhand smoke, manipulated nicotine to “create and sustain addiction” and falsely promoted low-tar cigarettes as safer than other brands. In all, it has alleged 145 acts of wire and mail fraud, linked to specific ads, news releases and pamphlets disseminated by the industry.

For their part, the cigarette makers accuse the Justice Department of rewriting history, in part by ignoring how the government “endorsed, participated in and often regulated much of the conduct about which it now complains.”

Said Bob McDermott, a lawyer for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co.: “The actions of the companies were perfectly understandable, perfectly reasonable in the context of the times, and we will lay that out in the course of the trial.”

According to cigarette makers, the Justice Department also has failed to acknowledge changes in the companies’ conduct, including their admission that smoking is dangerous and their pledge not to market to kids.

Few thought the litigation would get this far. Ordered up by President Clinton, who had bashed the cigarette industry like a pinata, the case did not fit usual Republican notions about the role of government.

“The Bush administration inherited” the case, noted William S. Ohlemeyer, vice president and associate general counsel of Altria Group Inc., parent of Philip Morris USA. “It is a prototypical effort to legislate through litigation, which is something they are on record as opposing.”

Early on, there were hints that the Bush administration was seeking a way to scuttle the suit. It initially budgeted only $1.8 million for work on the case, leading anti-tobacco lawmakers to complain that it would die of neglect. Then, after hinting that the case was weak, Justice Department officials sat down with tobacco executives in the summer of 2001 to talk about a settlement.

But those discussions ended abruptly when Justice Department officials declared that a deal would require a substantial payment, participants said. Lawyers at the department have been going full throttle ever since.

“We don’t talk about our internal deliberations,” said Mark Corallo, a spokesman for Atty. Gen. John Ashcroft, when asked about the resilience of the case. “If we take a matter to court, it’s because that’s where it belongs.”

Several observers said administration officials apparently saw little to gain -- and much to lose -- by pulling the plug. “There’s no political upside for doing anything” on behalf of the tobacco companies, said an industry representative who would not speak for attribution.

Alan Morrison, a senior lecturer at Stanford University Law School and founder of the Public Citizen Litigation Group, said it would have been tough for Bush and Ashcroft to explain why they dropped “a case that would bring in billions of dollars to the federal treasury, against companies that everybody thinks are very bad.”

The scale of the case is breathtaking.

More than 40 million pages of documents have been exchanged between the Justice Department and the defendants -- including Philip Morris USA, R.J. Reynolds, Brown & Williamson, British American Tobacco, Loews Corp.’s Lorillard Tobacco and Vector Group Ltd.’s Liggett Group unit. The parties have listed about 73,000 trial exhibits. And more than 300 potential witnesses have been deposed.

Legal bills have ballooned well into the hundreds of millions of dollars. With about 35 lawyers and 15 support staff members assigned to the case, the department has run up $139 million in costs, an agency spokesman said. With their army of top-flight corporate defenders, the tobacco companies have far outnumbered and clearly outspent the government, though they have declined to provide figures.

Heading the government’s tobacco team is Sharon Y. Eubanks, a 21-year veteran of the civil division who declined to be interviewed.

Presiding over the nonjury trial will be U.S. District Judge Gladys Kessler. The 66-year-old is a Clinton appointee and as a young lawyer co-founded a public interest law firm. No stranger to high-profile cases, she is the judge who ordered the Energy Department to release documents from the energy task force of Vice President Dick Cheney.

Kessler handed cigarette makers a big victory early on when she dismissed the government’s medical cost recovery claims -- originally the centerpiece of the case.

But most of her rulings since then have been much more favorable to the government. Last year, she fined British American Tobacco $25,000 a day for several weeks for failing to produce documents from an Australian affiliate. And in July, she ordered Philip Morris to pay $2.75 million in sanctions for violating a court order by destroying e-mails it was supposed to preserve.

Kessler also has rejected a string of industry motions to exclude evidence from trial and limit the amount of financial exposure.

For instance, she refused to keep out evidence concerning nicotine manipulation and marketing to kids. She also barred the industry from raising the defense that the government had supported and profited from its activities. And she declared that the industry’s settlement with the states did not rule out the risk of future misconduct.

In the most crucial pretrial ruling, Kessler refused to toss out the government’s $280-billion disgorgement claim. The astronomical sum reflects an estimate of 30 years of gross profits from sales to 33 million “youth-addicted” smokers -- defined as those who became regular cigarette users before the age of 21 between 1971 and 2001. The figure represents $75 billion in income from those sales, plus more than $204 billion in interest.

For the cigarette makers, a judgment anywhere near $280 billion would be a catastrophe and could easily throw them into bankruptcy. The companies did agree to fork over $246 billion as part of their settlement with the states, but with payouts stretching over 25 years, this effectively turned into a tax on smokers rather than a raid on company coffers.

In court papers, the industry chided the Justice Department for constructing “a model that does nothing more than come up with a big number in the hope that the threat of bankrupting liability will force defendants into a settlement.” The figure, the companies say, is wildly inflated because it does not distinguish between money fraudulently obtained and legal sales to smokers 18 and older.

According to the industry, the racketeering act, known as RICO, also limits disgorgement to ill-gotten gains that are likely to be used to commit fraud in the future.

Kessler’s ruling did not endorse the government’s calculations but gave Justice Department lawyers a chance to back them up at trial. The judge, however, agreed in July to let the companies appeal the disgorgement ruling without waiting for the end of the proceedings. With oral arguments not scheduled until November before a federal appeals court, the trial will be far along before the panel rules on the disgorgement issue. Kessler last week denied an industry motion to postpone the trial until the appeal was decided.

Of course, the $280 billion is hardly the only potential cost faced by the industry.

Even if the companies win at trial or on appeal, the notoriety of the case is likely to undermine their efforts to remake their image, and it could batter their shares. As Rob Campagnino, an analyst with Prudential Equity Group, said in a note to investors: “An airing of the industry’s dirty laundry, real or perceived,” is not likely to help anybody’s stock price.

Observers say the case also could highlight a growing split within the ranks of the once-monolithic tobacco industry.

Philip Morris, whose market share has grown to about 50%, stands alone among the companies in supporting legislation to give the Food and Drug Administration authority to regulate tobacco products. Philip Morris also has stopped advertising its brands in magazines, going beyond advertising curbs negotiated with the states.

By contrast, Brown & Williamson and RJR have come under attack for what authorities in some states deem to be targeting of kids.

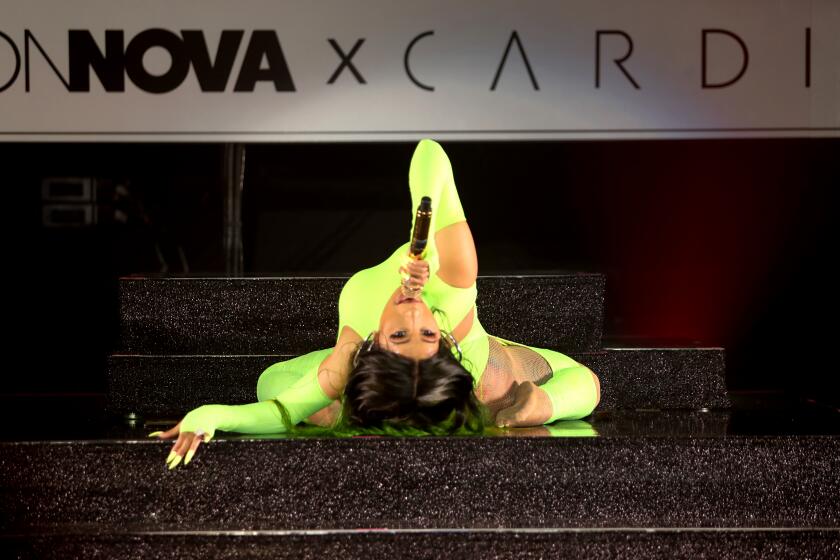

B&W; has been sued by Maryland, Illinois and New York over a hip-hop-themed “Kool Mixx” campaign for its Kool cigarettes. And Hawaii Gov. Linda Lingle recently blasted RJR for a Camel ad blitz featuring girls in grass skirts promoting Kauai Kolada and Twista Lime flavored versions of the cigarettes. Dan Donahue, senior vice president and deputy general counsel at RJR, said all advertising campaigns were carefully vetted for compliance with terms of the settlement with the states.

Such squabbles could undermine one of the industry’s basic contentions -- that it has reformed itself and does not need the oversight of a federal court.

Philip Morris “at least understands that there’s a DOJ case out there,” said Richard Daynard, chairman of the Tobacco Products Liability Project, an anti-tobacco group.

For the other companies to “roll out all these candy-flavored cigarettes” as the case heads for trial, said Mitch Zeller, a former official with the FDA, it “doesn’t make rational sense.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.